Vuelta a España reaches emotional highpoint at Angliru – Stage 17 preview

Hardest climb in Spain has ultra-steep slopes that could light the fuse for GC battle

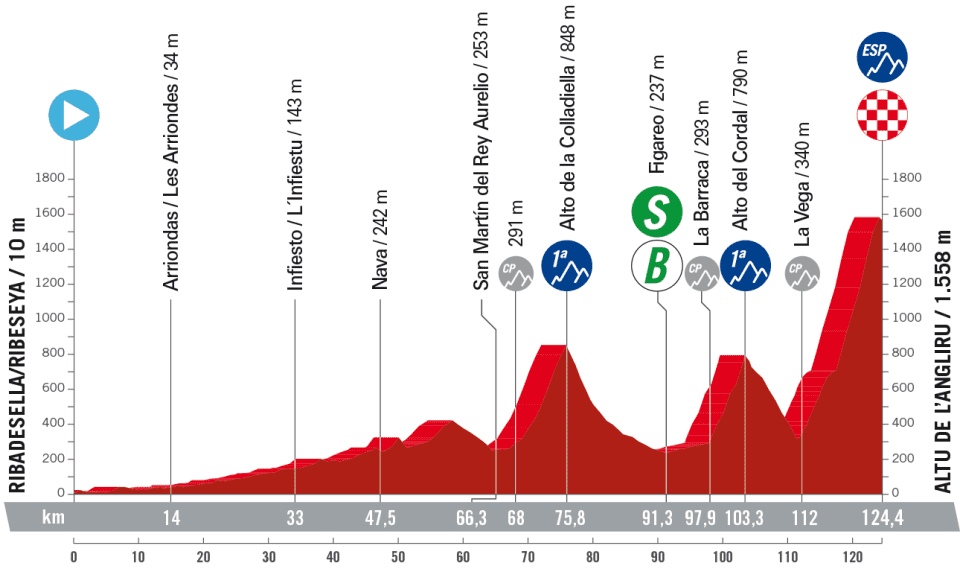

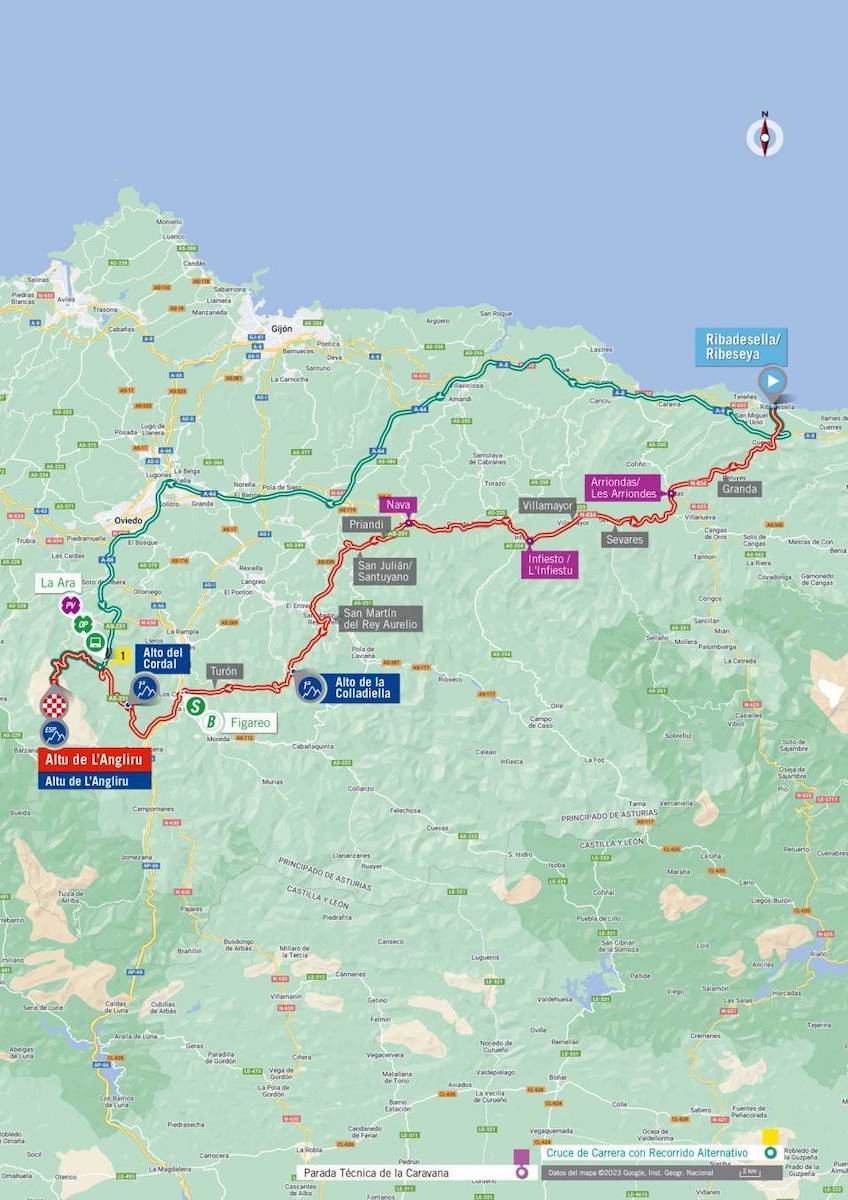

Stage 17: Ribadesella / Ribeseya to Altu de L'Angliru

Date: September 13

Distance: 124.5km

Stage type: Mountain

For the Vuelta a España no other climb matters as much as the Altu de L'Angliru.

This year’s race has already tackled Pyrenean climbs as prestigious as the Tourmalet, the Aubisque and the Col de Larrau and is yet to face a fearsome double ascent of the little-known Cruz de Linares on Thursday. But the Pyrenean climbs are all in France and have deep links to the Tour, not the Vuelta. In terms of the Spanish race when it comes to emotional high points, the Angliru towers above them all.

The Angliru’s place in the heart of the Vuelta is all the more remarkable given that, unlike the Tourmalet in the Tour, the Asturian monster climb is a relatively recent addition to the race route. It was first tackled in 1999, with a victory for the late José María Jiménez.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But since then the Vuelta hasn't been able to get enough of the Angliru. It has been part of the race no less than seven times, most recently in 2020, the year of the pandemic, with a win for Britain’s Hugh Carthy (EF Education-EasyPost).

“The Angliru is a climb that marks you, but in my case in a good way, it’s my favourite climb of the whole Vuelta,” retired rider Robert Heras, who holds the record for the ascent at 41:55, tells Cyclingnews.

“I’ve been up there four times in the Vuelta and I can confirm it’s not just a special ascent because of its difficulty. It’s also one where you can get big differences on your rivals, and which can change the course of the race.”

It’s true that actual victory in the Angliru is far from certain to guarantee an overall triumph in Madrid. Only once in the last eight ascents, in 2008 with Alberto Contador, has the Vuelta’s stage winner on the Angliru also won the race outright.

However, the Angliru has seen the race leader change four times: in 2002 Heras replaced Oscar Sevilla atop the GC; in 2008 Contador ousted Egoi Martinez; in 2011, Cobo, albeit prior to disqualification, supplanted Sky’s Bradley Wiggins; and in 2020, Richard Carapaz briefly squeezed out Primož Roglič from the top spot overall.

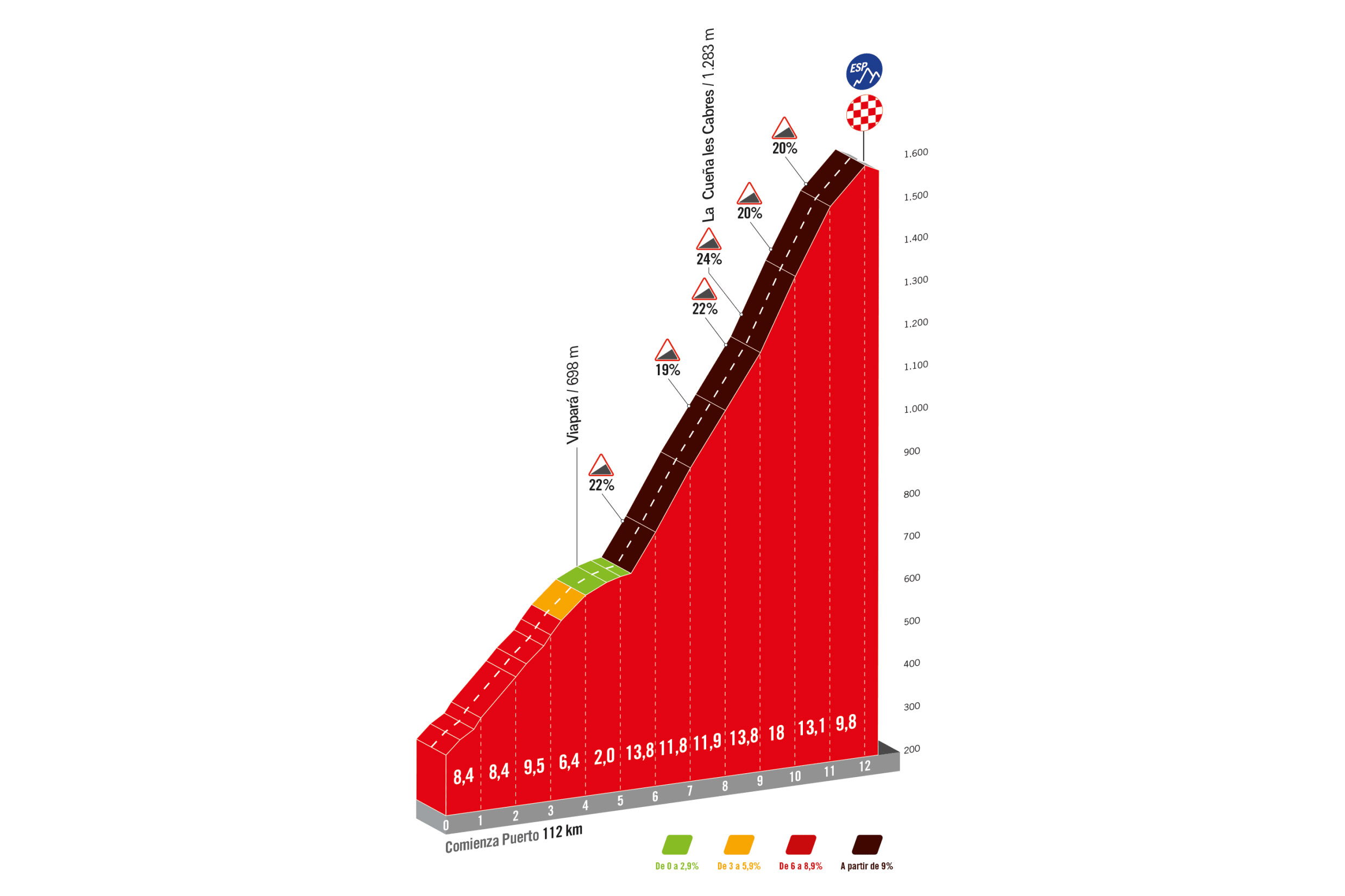

Two sections

The first 5.5 kilometres are not so hard, but from that point onwards, on ramps known as the Viapará, the road rears more steeply and the average gradient shifts to 10.1%. On such steep slopes, the stage switches from being a normal race into the toughest of uphill individual time trials.

Hard as 10% may sound, on the Angliru those are the easy parts, with mid-climb challenges like the Cuesta les Cabanes ramp, at 21.5% pushing the riders into the reddest of red zones.

There is a brief respite of sorts at kilometre 8.5, where the ramp’s percentage points drop to a mere 14.5%. But then as the race swings right for another kilometre-long straightaway, we’re back up to a more standard, horrendously hard, 20%.

Could it get any worse? Of course it could, this is the Angliru. With just 2.5 kilometres left to go, the steepest corner of the entire climb, so well-known it actually has a name - Curva de los Cobayos or the improbably named ‘guineapigs corner’ - leads directly onto the 1.3km-long segment called Cueña les Cabres or ‘the goats’ track’, as it is rather more aptly called.

By far the hardest part of the Angliru, with an average of 18% and the toughest segment at 23.5%, the Cueña les Cabres is where the massed lines of fans traditionally gather, where team and media car clutches burn out, where riders suddenly reach the end of their strength and where, perhaps, the Vuelta may be won or lost.

The last part of the climb maintains the pain, with the final hard segment of El Aviru, which has slopes of 21% and 1.5km to go, very likely to broaden any gains made by a breakaway on the Cabres ‘ramp’. Finally, after a short descent and quick kick back up in the final kilometre to the Picu del Puerto finish, the ascent is over: 1,266 metres of vertical climbing to 1,573 metres above sea level.

That is the climb itself, but the weather, Heras says, is critical in how things may play out on the Angliru on Wednesday afternoon. Rain is forecast in Asturias and as Heras says, “It’s a completely different ascent in the wet and in the dry”.

“I remember in 2000, when I set the record for climbing the Angliru, it hadn’t rained, and then in 2002, when there was a downpour, even though I was in better form, it all went a lot slower.

“The difference because it's so steep, in the wet you can’t stand on the pedals your back wheel skids all over the place.” The knock-on effect, then, is that attacks are much harder to sustain, or have to be in the form of steady accelerations rather than sudden changes of pace.

It’s often remarked on such ultra-steep climbs that teamwork is virtually impossible and the race becomes much more of a hand-to-hand struggle between individual riders. Heras only partly agrees, though.

“The thing is that the Angliru is actually two climbs, as the first five kilometres or so are not that hard.

“In that part, teamwork is really important for wearing down the rivals. But then in the second half, the worst thing is that the steepness never really eases at any point, and there’s nowhere that you get even a moment to catch your breath. For five or six kilometres.

“That said, even if you can’t follow somebody’s wheel, having a teammate with you if possible is important at that point, because it it acts as psychological support.”

Additional variables

The other key element of support is the fans, Heras says. Notably missing from the last ascent of the Angliru in 2020 because of the pandemic.

"Riding through a solid line of people supporting you is one of the greatest things about the Angliru," Heras says. "There’s a huge cycling fanbase in Asturias and I remember going up La Cueña de las Cabras with the people yelling and cheering you on gave me goosebumps. It was a really special moment, one of the most beautiful experiences a rider can have.”

On such an exceptionally difficult ascent, knowing how to manage the climb in terms of your internal strength is fundamental, Heras says.

“To ride the second, hardest part of the Angliru well, you have to know how to exert yourself to the maximum on a really steep slope: but – and this is critical – it's also about keeping in mind that there are no breaks in the steepness.

"So you can’t go over your limit, because if you do, there’s no way back into the game. The climb is that hard.

"You have to calculate your strength really, really carefully, so you know that you won’t tip yourself over the edge - watching your watts for 'x' minutes, your pulse rate, everything. You have to keep on remembering you have to keep that particular level of intensity all the way up to 500 metres from the line when there’s a slight downhill…”

It's something that, on a climb as tough as the Angliru where the stress and lactic acid levels are so high and so much is at stake, is far easier said than done.

Those riders who know a climb as difficult as the Angliru, Heras says, will definitely have the edge on those who do not, given the importance of managing your effort and knowing what the climb implies for that.

"Above all, though, the Angliru ends up not being about attacks, as such, because it’s so hard. It’s more about setting a specific constant, pace, sticking with it and seeing where it gets you by the top.

"You can’t go at 12kph and then suddenly jump up to 18 kph in an attack. Because you’d end up paying for that change in effort, really fast.”

Wednesday isn’t just about the Angliru, though, with two category 1 climbs in the first part of a short, punchy 124km stage. After the Alto de la Colladiela, the Vuelta then tackles the Alto del Cordal, an old favourite of the race and for the last two decades it has almost invariably preceded the ascent of the Angliru.

Although steep, it’s short and the real challenge of the Cordal is its descent. It’s well known to be a skating rink in wet weather and once caused a change of leader. In 1999, Abraham Olano fell and cracked a rib there, and although he hung on to first place overall on the Angliru, he finally ended up ceding the top spot overall because of his injury.

“I remember that year on the descents of the Cordal and the climbs beforehand, I’ve never been so scared in my life,” Heras, third on the Angliru in 1999, recalls. “Almost everybody crashed that day. One thing is clear: as soon as it rains in Asturias, then the climbs like El Cordal are much tougher.

“If it’s wet, the Vuelta will already have taken shape and some riders will be out of the picture even before the race reaches the Angliru. I remember one year my team, Kelme, attacked on those descents and we managed to shake off a contender as dangerous as [2007 Vuelta winner] Denis Menchov.”

As for who could be in the mix on Wednesday, “Right now, though, Sepp Kuss is going really well, but my favourite to win the stage is Jonas Vingegaard. He’s getting better and better as the Vuelta goes on.”

Not only that, after winning on the Tourmalet in France, capturing the Vuelta’s most prestigious stage inside Spain could even gain Vingegaard the overall lead as well.

The Angliru, then, is not just an emotional high point for the Vuelta. It could, once again, be the moment around which the whole race pivots.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.

Latest on Cyclingnews

-

'I saved it for the last lap' - Tibor Del Grosso put pressure on Thibau Nys across final hill to secure silver in first elite appearance at Cyclo-cross World Championships

'I think it proves that I belong in the top of the sport' two-time U23 'cross world champion confirmed -

Arianna Fidanza sprints to victory at Pionera Race-SCV

Laboral Kutxa-Euskadi grabs ninth team victory on early season, with Laura Asencio's second place a milestone for new French team Ma Petite Entreprise -

'I was prepared for any scenario' – Mathieu van der Poel says he took more caution as he chased record-breaking eighth cyclo-cross world title

'Maybe it's not a bad idea to skip one winter' Dutchman adds as he turns focus to upcoming road season -

Thibau Nys gets stuck on wrong tyres after late rainfall and salvages bronze for Belgium at Cyclo-cross World Championships

'Losing a couple of seconds every corner was not nice, but Mathieu was the strongest, so we don't really have the feeling that we missed out on a title or anything'