Wheelmen book excerpt: What to do about Lance Armstrong (part 3)

Landis feels the weight of the omerta

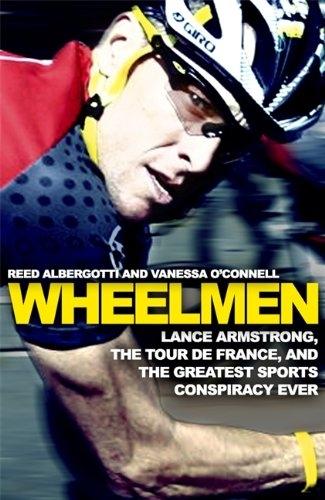

"Wheelmen" by Reed Albergotti and Vanessa O’Connell - reveals new details of Lance Armstrong's secret past and eventual downfall thanks to a detailed interview with Floyd Landis and numerous other people who were close to him.

Cyclingnews has obtained an excerpt from Wheelmen which will be published in two parts. The first part told the story of Floyd Landis’s decision to confess to doping and how Armstrong and those who supported the Texan tried to stop him. It reveals the secret influence Armstrong held over Landis and how he and others used it.

This second part details the impetus behind Landis composing the fateful email providing the initial details about the doping program within the US Postal Service team, which was sent to USA Cycling and the UCI. Also included is the means by which Landis ultimately met and confessed to USADA's Travis Tygart.

In this third part, Landis feels the weight of the omerta bearing down on him.

Wheelmen can be purchased in bookshops and online by multiple retailers, including Amazon.

Chapter 11: Adieu and Fuck You (excerpt 3)

The answer was a red flag — a bombshell of an answer that almost counted as an admission. Fifteen minutes after the press conference, Landis's phone rang. It was Armstrong calling with some advice. "Look . . . when people ask you . . . did you ever use performance-enhancing drugs, you need to say abso-lutely not." Landis agreed. He would steadfastly deny doping from that point forward.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Landis flew back to the United States and tried to figure out what to do next. He spoke with a number of confidants. For a while, he stayed in the Manhattan home of Doug Ellis, a wealthy and successful financial industry software engineer who was considering starting a cycling team. At Ellis's suggestion, Floyd met with Jonathan Vaughters, who was now team director for a semipro cycling team. Vaughters saw no easy way out of it, though. He knew that the anti- doping machinery had become too powerful. Landis would never make it through. Floyd's best option, Vaughters suggested, was to admit everything. To lay everything on the table, even if that meant blow-ing up the sport. If he did that, Vaughters said, the story would become about cycling, and not about Floyd. It would lift an enormous weight off of Floyd's shoulders. If he fought, as Hamilton had, he would lose, and discredit and bankrupt himself.

Vaughters of course had his own secrets, and knew all about the weight of carrying them. Having lied to his friends and family about doping for years, he was dying to disclose the truth about his own doping. But the closest he had come to doing so was to allow the New York Times reporter Juliet Macur to quote him anonymously in a story she had written about Frankie Andreu. In the story, she reported that both Andreu and an unnamed rider had admitted using EPO, but that neither had seen Armstrong do so. In fact, Vaughters had told Macur that he would not answer that particular question — which he thought was a clear way of saying, "Yes, I saw Armstrong dope. I'm not going to deny it, but I'm not going to confirm it, either."

Landis began to seriously consider coming clean. But when he spoke again with Armstrong as well as other people in the cycling industry, they all advised him to fight the charges. He couldn't admit to doping, they said, because a revelation could expose the entire team as well as its support staffers. Landis still hoped to get back into the sport, and bombshell allegations would eliminate that possibility.

About a month after Landis's positive test, his father-in-law and best friend, David Witt, committed suicide, shooting himself in the head. The co-owner of a local restaurant and an avid bodybuilder, Witt had become one of Landis's drug suppliers. Witt got prescriptions in his own name for the drugs Landis needed — including testosterone and human growth hormone. Though Witt had long suffered from depression, Landis was certain his own disgrace had at least contributed to Witt's suicide.

Landis was devastated and depressed. It felt as if his life was in the middle of a massive mudslide, wiping away everything in its path.

Anguished and desperate, Landis again reached out to Jim Ochowicz. He figured Ochowicz was one of the few people who would understand the situ-ation he was in and be able to advise him about what to do. Ochowicz had been there in St. Moritz when Landis and Armstrong were training with Michele Ferrari. And Ochowicz knew everything there was to know about the cycling world. Not only was he still the president of USA Cycling, and still an employee of Thom Weisel's, but he knew all the key players, including of course Lance Armstrong, with whom he was close.

When Landis called, Ochowicz was staying in the Hollywood home of Sheryl Crow. She was a good friend, and had remained so even after she and Armstrong split up. Ochowicz invited Landis to come and talk. Landis drove his Harley- Davidson up from Temecula. Crow brought the two men drinks and sandwiches, then left the house about ten minutes later. As they sat on her veranda overlooking downtown L. A., Landis said, "Listen, you know what's going on in cycling. You and I both know about the doping programs on every team you've ever run, certainly the US Postal team."

"Yeah, yeah," Ochowicz responded.

"I can't fight it anymore," Landis said. "I don't want to be broke and feel guilty, and that's what's about to happen. I don't mind being broke, but I'm not going to feel shitty anymore," he said. "My two choices here are either fight this or just admit to it and clear my conscience. I'll tell you what I'm not going to do. I'm not going to take the fall for this sport and walk away and just get beaten up the rest of my life. At the very least, I'm going to clear my conscience."

Ochowicz gave Landis some firm advice: He should say nothing. Nobody would believe him anyway. The allegations would drag down the entire sport and ruin not only his career but the careers of others. The only option was to fight the charges in every way he could, Ochowicz said. Floyd didn't explicitly ask Ochowicz for money, but it was clear that was what Floyd needed if he were to continue his denials. "Look, I need some support," Landis pleaded.

"Let me make some phone calls and I'll let you know," Ochowicz said.

A few days later, Landis got a call from Bill Stapleton, who demanded to know why Floyd had asked Ochowicz for money. Floyd explained that he was short on cash and could use some help. Over and over, Stapleton kept asking him, "Why should we help you out?" Landis felt that Stapleton was trying to goad him into threatening them with extortion if they didn't give him money.

Despite Stapleton's call, Armstrong did arrange to help Floyd. Not directly — Armstrong couldn't risk the association — but he connected Landis to some of his own wealthy backers, like Thom Weisel and John Bucksbaum. Tiger Williams, whom Landis already knew, also helped out. If Landis stayed quiet about the doping, there was an enticing carrot: money to help him fight the US Anti-Doping Agency.

But if he came clean in order to clear his conscience, he knew there was a giant stick: the wrath of Armstrong. Lance, Stapleton, and their powerful friends would try to discredit and destroy him.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just $1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

After your trial you will be billed $7.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just $79