UCI serious about mechanical doping but number of tests remain low

Governing body testing wheels and riders' spare bikes but no checks in the Pyrenees

The UCI have acknowledged that they have no proof of mechanical doping within the professional ranks, however they have admitted that as motorised bikes exist on the market, so does the possibility of motorised doping.

Yet despite this very real threat the governing body have only carried out tests on four out of a possible 18 stages in this year’s Tour de France, with a large proportion of the 25 tests conducted during the team time trial on stage 9. To date, only one mountain stage in the race has been subjected to testing.

“For years we’ve been taking this seriously by checking bike at races,” a UCI spokesperson told Cyclingnews.

“We’ve heard the rumours. The main fact is that we know you can buy such bikes on the market and restoring credibility in the sport is important.

“We know that the technology is available on the market. We’ve been making checks as we don’t want this to enter professional cycling. This was mentioned in the CIRC report but we didn’t wait for the publication of that to confirm it. We’ve been taking this seriously for much longer.”

However the UCI would not comment on the number of tests carried out in the Tour de France and why there had been no tests in the first number of mountain stages or after stage 19, the most mountainous stage in the race.

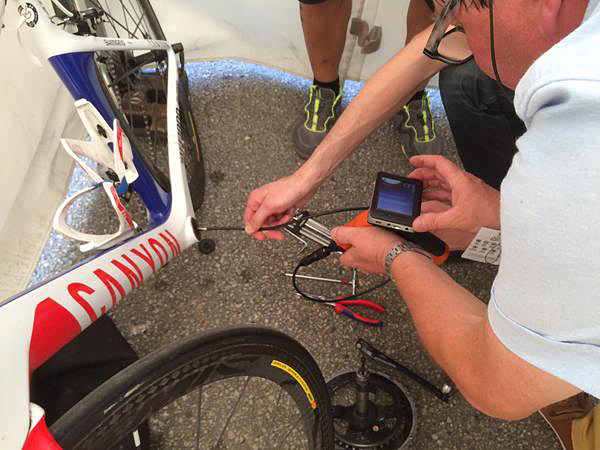

The UCI also confirmed to Cyclingnews that tests are not just in relation to frames, where a motor might typically be housed. The governing body added that they also check the wheels on each bike that they analyse at race finishes. These tests include examination of the bearings and/or additional components, which may include such things as magnets.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“We then remove the wheels from the bike and give them a visual check to look for signs of any modifications. The wheels are then checked for balance which would indicate the presence of additional components and finally we check the bearings run smoothly and without resistance which would also indicate the presence of additional unauthorised components.”

There have been several unsubstantiated reports of mechanical doping already seeping into the professional ranks. Questions were first raised years ago during the Classics campaign of 2011, again at the Vuelta last year, and this year Alberto Contador was forced to rebuff allegations that there was a motor in his Specialized bike.

Prior to the Tour de France the UCI have carried out a number of batch tests of bikes at races, starting with Milan-San Remo, and then following on with the Giro d’Italia, Critérium du Dauphiné, and now the Tour. The operation at Milan-San Remo was by far the biggest with over 30 bikes analysed from Trek Factory Racing, Etixx-Quick Step, Tinkoff Saxo, Katusha, as well as the top three riders.

“We’ve not gathered any proof so far but again we believe it’s the UCI’s responsibility to ensure that racing is clean so that by carrying out these controls we’re taking our duty seriously. We don’t have any proof that it’s happening now, though, or that it’s happened in the past. We know that it’s on the market and that companies are testing and new products are being made. We’ve not found any motor or engines on bikes we’ve tested though,” The UCI stated.

The governing body also confirmed that when a rider is targeted for motor testing his entire entourage of bikes are analysed – not just the one he happens to cross the finish line on. Such a measure is there to ensure that bike changes – a regular occurrence from the top level pros either due to mechanical problems or weight saving – are not used to cover up cheating.

“We check all the bikes of a rider. So if we decide to check rider A or rider B or C we check all his bikes, whether they are used or not. So if they’re on the team car we check them too,” the UCI spokesperson added.

The UCI has also introduced new sanctions within their regulations, should riders be caught using illegal mechanical assistance. These include up to six month bans and fines.

“The UCI takes extremely seriously the issue of technological fraud such as concealed electric motors in bikes, and has therefore added far-reaching sanctions in its Regulations. We have been carrying out controls for many years and although those controls have never found any evidence of such fraud, we know we must be vigilant. We have carried out several unannounced checks on this year’s Tour de France.”

Daniel Benson was the Editor in Chief at Cyclingnews.com between 2008 and 2022. Based in the UK, he joined the Cyclingnews team in 2008 as the site's first UK-based Managing Editor. In that time, he reported on over a dozen editions of the Tour de France, several World Championships, the Tour Down Under, Spring Classics, and the London 2012 Olympic Games. With the help of the excellent editorial team, he ran the coverage on Cyclingnews and has interviewed leading figures in the sport including UCI Presidents and Tour de France winners.