UCI defends mechanical doping testing procedure

Governing body hits back at claims the device can only detect rudimentary motors

The UCI has responded to accusations that its tablet device struggles to detect the latest forms of mechanical doping and may throw up false positives by claiming the simple technique of magnetic resistance scanning using a tablet device has "proved to be highly effective both in tests and in actual use".

Claims of mechanical doping at the Tour de France in CBS 60 Minutes investigation

Bruyneel blasts LeMond for 'obsession' with Armstrong and mechanical doping

Italian amateur denies using mechanical doping

Doubts raised over effectiveness of UCI tests for mechanical doping

UCI's mechanical doping tests called into question - Video

Nibali vows to fight on at Vuelta a Espana

Froome: I couldn't start a race if I believed someone was using a motor

The UCI claimed that "all stakeholders in cycling have a common interest to demonstrate that cheating has no place in our sport", and provided an email address for anyone to supply information about possible mechanical doping.

The effectiveness of the UCI's tablet device has been doubted by another investigation from the French Stade 2 television show, with help from German television channel ARD and Italian journalist Marco Bonarrigo who writes for the Corriere della Sera newspaper.

Stade 2 also revealed that the UCI's tablet application was created by a tiny start-up company based in Britain, called Endoscope-i, which was created on the back of an iPhone app that works as an endoscope.

A political issue

The suspicions of mechanical doping have become a political issue because of the UCI presidential elections scheduled for September 21 at this year's World Championships. French candidate David Lappartient, who has been the UCI vice-president alongside Brian Cookson for the last four years, was interviewed for Sunday's Stade 2 show and called for multiple techniques such as x-rays and heat guns and the dismantling of bikes to be used alongside the tablet device to search for hidden mechanical doping.

The UCI responded to the latest accusations by pointing out that Cookson introduced the rules against what is officially called 'technological fraud' during his first term as president.

The rules and lengthy bans came into force a few months before a hidden motor was discovered in the bike of Belgian rider Femke Van Den Driessche at the 2016 cyclo-cross World Championships. More recently, a similar hidden motor was discovered in the bike of an Italian veteran racer competing in an age-related race in Brescia. However, there have been several reports that far more sophisticated electro-magnetic wheels have been used in the professional peloton. Stade 2 accused the UCI of being unable to detect the so-called 'magic wheels'.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In its statement the UCI did not specifically respond to questions about the failure of the tablet device to find the electro-magnetic wheels, claiming it has "analysed many alternative forms of detection" to "ensure a varied testing protocol".

Responding to Stade 2

The UCI suggested that "people using our device in Sunday's Stade 2 report had had no training". That is true because the UCI has always refused to allow anyone to study the tablet device in detail. A simple demonstration was held in the spring of 2016 but the UCI has always been defensive of its technology and techniques and rebuffed questioning.

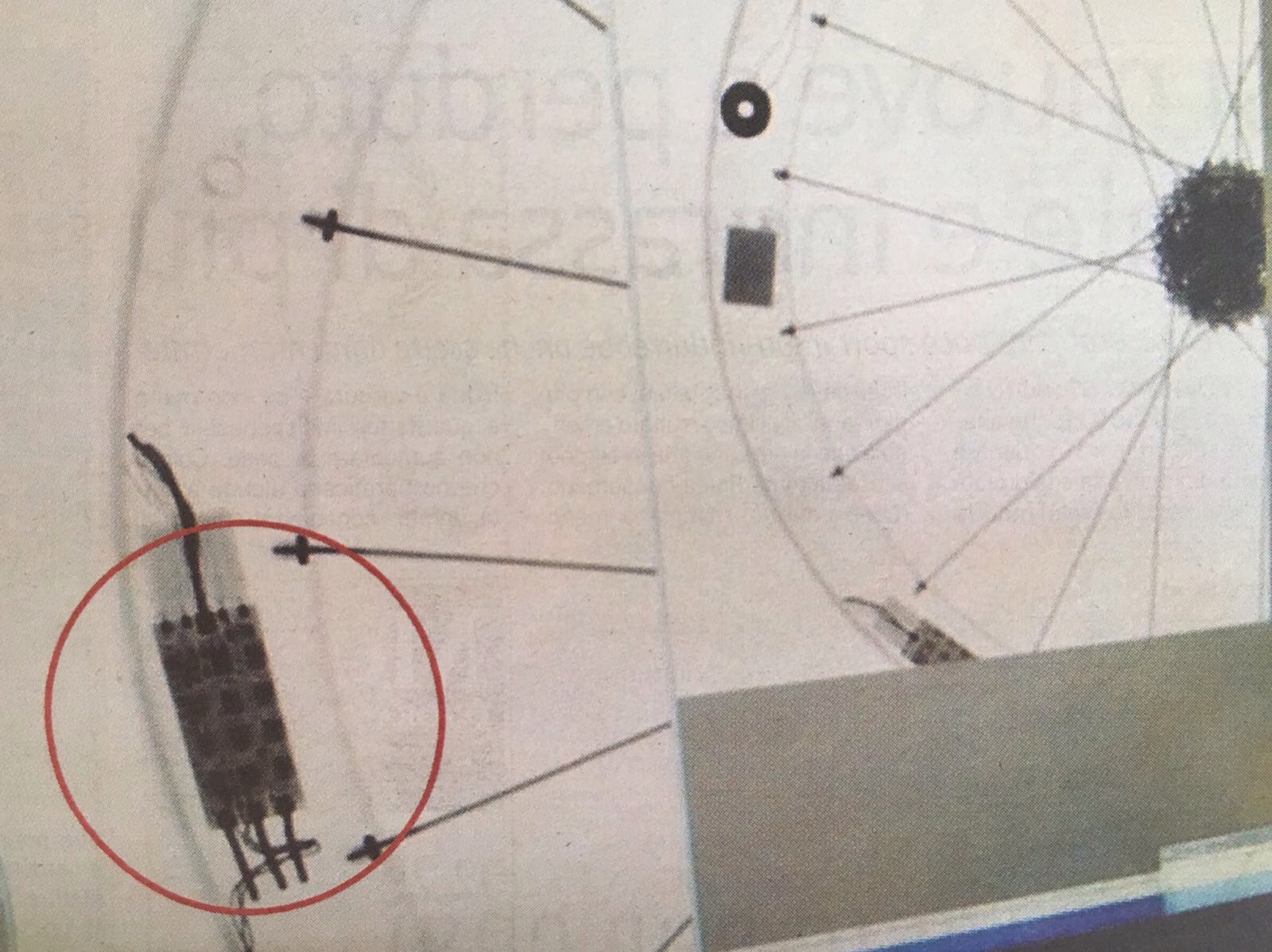

An independent report by the US-based Microbac laboratory highlighted that the positioning of the tablet device when searching for mechanical doping was vital, with an optimum distance of 10mm from the frame. Stade 2's tests showed that the there was a reaction from the tablet when passing over metallic parts of the bike, with closer and longer scans needed to provide a clear indication of a hidden motor. However, their documentary showed footage of UCI checks being carried out at races where the scanner was being moved rapidly and the checks completed in just a few seconds.

The UCI has always defended the use of the tablet device due to its ease and speed of use at races.

"Our training always emphasises that the scanner is for initial controls and that bikes must be dismantled should any suspicion of the presence of a motor or any other hidden device be indicated," the UCI press release states.

"The UCI has of course analysed many alternative forms of detection, and indeed continues to make use of alternative methods in combination with magnetic resistance scanners to ensure a varied testing protocol. However, all alternative forms are not suitable to be the main or exclusive form of detection.

"Thermal imaging has been used on a number of occasions and can be useful, but is limited as it would only detect a motor when in use, or shortly after use when a motor is warm. We also occasionally use X-ray, but this is relatively slow, requires a great deal of space to ensure public safety, and is subject to widely varying legislation from country to country.

"We continue to work with our partners to ensure we keep up to date with developments in this area and are grateful to the many people and organisations who have helped us develop a highly effective suite of controls and the associated rules and sanctions for potential infringements.

"We remain committed to this work and welcome all input and suggestions as to how this can be developed further. All stakeholders in cycling have a common interest to demonstrate that cheating has no place in our sport. If anyone believes they have information that we should be aware of, we ask them to please contact us at materiel@uci.ch."

Stephen is one of the most experienced member of the Cyclingnews team, having reported on professional cycling since 1994. He has been Head of News at Cyclingnews since 2022, before which he held the position of European editor since 2012 and previously worked for Reuters, Shift Active Media, and CyclingWeekly, among other publications.