Tour of California officials: 'Perfect storm' led to dangerous situation for Skujins

Race director and doctor address Skujins concussion incident

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Amgen Tour of California officials said Tuesday that the incident involving Toms Skujins (Cannondale-Drapac) being pushed back into the race after suffering a concussion in a crash was due to a 'perfect storm' of circumstances that created a potentially dangerous situation for the rider and his fellow competitors.

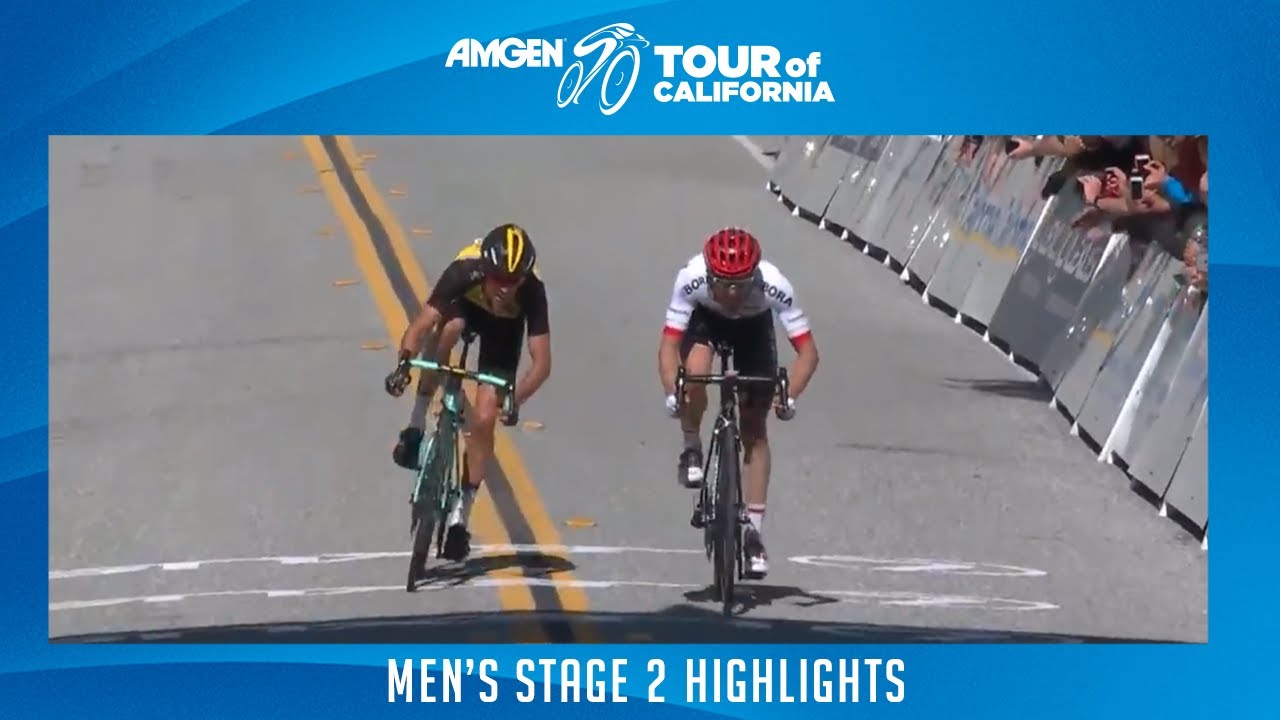

More than 24 hours after an obviously distressed and injured Skujins was pushed back into the race by neutral support following a hard crash during stage 2, Race Management Director Jean-Michel Monin and Race Doctor Ramin Modabber addressed the incident and took questions from the media.

Skujins had been in the early breakaway and then soloed on alone after Mt. Hamilton before being caught by the GC group that had been chasing him. The Cannondale rider tagged onto the back of the group but then hit the deck while descending off the Quimby Road climb with 22 kilometres remaining.

Skujins had trouble standing and fell over when he initially tried to remount his bike. The neutral mechanic then assisted Skujins and pushed him back into the race. Monin said his car came up alongside the rider about a minute later, then Skujins' team car and the medical car arrived another 1:45 later and were able to coax the rider off his bike.

Skujins suffered a concussion, broken collarbone and abrasions in the crash, but he was not injured further after re-entering the race. Nevertheless, serious questions arose from horrified observers who watched the mechanic push the distressed and injured rider back into action.

While many people voiced concerns on social media about the mechanic's decision to help Skujins back into the race, others pointed out that the mechanic was simply doing his job, which does not include making medical diagnosis about a rider's physical condition.

"Should we allow SRAM service to pull a rider?" Modabber asked. "You're going to be having some conflicts there because a rider may disagree. In a straw poll of athletes who reached out to me, they said unless my teammate, my director or a doctor comes up and tells me I'm not riding and I don't look good, I'm probably going to keep riding, because that's what I'm trained to do.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"So it is a bit of a perfect storm in this situation, and the optics, because we have HD cameras and worldwide viewing, it's difficult. But I think each step along the way people are trying to do their job and trying to do the right thing."

Head injuries are not an easy thing to diagnose, Modabber added, saying it's a very complicated issue and that the nature of cycling, a dynamic event that is constantly on the move, creates extra complexities for race personnel.

"This is not a football game where you can remove them, examine them and run sophisticated tests and then let them come back in in five minutes if they pass, or not, pull them away, take their helmet. That's a totally different situation from what we face in a cycling race," Modabber said.

"We are forced really in a matter of seconds to make a decision about a head-injured athlete, and we base it mostly on observation an experience more or less. If there is a witnessed loss of consciousness, the rider is pulled. If they're riding the bicycle and you come alongside them very much like yesterday, and you have a conversation with them and they say, ‘I'm either going to see you in the medical tent or I'm going to go back to my team car,' then you would respect that decision as well."

Asked abut concussion protocol within the race medical staff, Modabber indicated that the only thing that will lead to a rider being removed from the race without question is if the athlete has been unconscious following a crash. Other than that, the decision is made on a case-by-case basis.

"This is an extremely complicated grey area situation, but a head-injury athlete is a very complicated topic, and when you're forced to make a decision you typically err on the side of an awake, alert, conversant athlete who continues to ride their bike where you can watch them," he said.

"We tell team directors to respect our decision to pull an athlete, and the only thing we'd really step in as a medical practitioner is a head injury," he said. "We don't think necessarily team directors want to do that, and if we feel it's obligatory we might have a disagreement and we would probably put our foot down. But it's a difficult thing to do and you would probably only do it if you had pretty solid evidence that this is not safe for that athlete."

In the end, Modabber said, everyone in the Skujins incident did their job properly and cannot be faulted.

"The optics, I agree 100 percent, are difficult to watch and explain each piece," he said. "But if you break them down it's pretty clear to me that a situation could happen identically and nobody really would be faulted, and here's why: SRAM's role is pretty focused on putting an athlete back on their bicycle or mechanical assistance, and they're really not trained or qualified to assist a head-injured athlete.

"I think even a layperson with a knowledge of head injuries from all of the reports that are out there about head injuries can look at that situation and say, ‘I might have done something differently.' But in the heat of the moment, I think their focus is not necessarily on the head injury but on the mechanics of the bicycle, etc."

Growing up in Missoula, Montana, Pat competed in his first bike race in 1985 at Flathead Lake. He studied English and journalism at the University of Oregon and has covered North American cycling extensively since 2009, as well as racing and teams in Europe and South America. Pat currently lives in the US outside of Portland, Oregon, with his imaginary dog Rusty.