Stetina: I have to let the races beat me up and then come back stronger

American discusses recovery and rider safety as he starts 2016 season in Europe

The scars from Peter Stetina’s fractured tibia and patella injuries in his right knee are still clearly visible. The anniversary of his terrible crash in the 2015 Vuelta al País Vasco is fast approaching, but Stetina remains focused on his long battle to return to full strength as a professional in Europe.

“It’s coming well, there’s no pain racing, which is really nice but it’s just the muscle is taking a little while to come back,” Stetina explained to Cyclingnews at the recent Vuelta a Andalucia.

“When you don’t walk for four months, you lose so much strength," he said. "Even though everything points well in training, it’s those high-power race accelerations that you can’t really practice and the muscle still gets fatigued a little earlier than normal.”

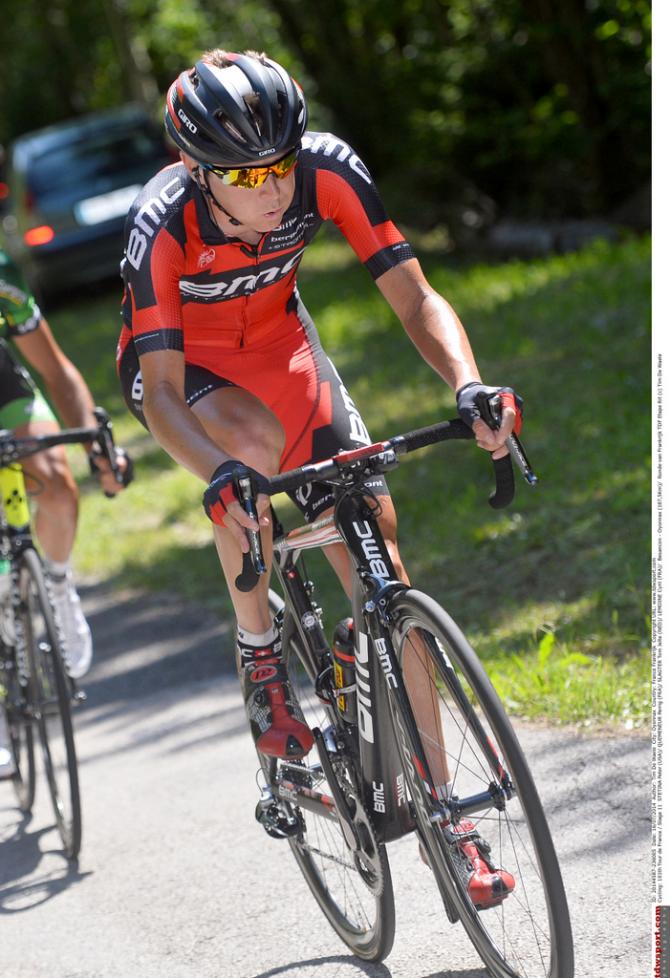

Despite having spent so much time without walking following the crash, Stetina’s determination to make a return to racing drove him to race at the end of 2015. He placed 81st in the Tour of Utah on less than a month’s training and 29th in the Japan Cup. This year, now with Trek-Segafredo after leaving BMC, he was 35th overall in the Santos Tour Down Under and finished 48th at the Vuelta a Andalucia Ruta del Sol.

Stetina says he feels better after every race he does. "At the Tour Down Under I was getting more fatigued, and here I’m feeling better later in the finale. It’s still got a ways to go. It’s just one of those waiting things where the more racing I do the more it comes back.”

Recovery is a slow process

Time may be a great healer, then, but as Stetina points out, it’s not a quick process. This, in turn, has a knock-on effect on what each race goal can be for the Trek-Segafredo rider.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“A lot of doctors say that at the very minimum, even with a great recovery, it’s a minimum of a year probably to being somewhere normal,” he explained. “So I try to help the guys as much as I can, the team have been really good at being patient with me because all the signs are that I’ll be back. I've just got to keep my head down, continue the gym work, let the races beat me up and then come back stronger.

"It really is about ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’.”

Stetina says he will be doing roughly the same amount of racing in the first half of 2016 as he had planned prior to the crash in 2015, although doing a few extra events remains a possibility. But it’s important to let his knee take the time it needs for a proper recovery, too.

“It’s a balancing act, you can try to rush it, but maybe that’s not the best long-term. It’s almost better to just know that it’ll naturally come back and you got to let the recovery run its course. All the signs overall still point to me being able to come back,” he said.

Such a lengthy recovery process represents a voyage in the dark, with few points of references and particularly given that injuries of this magnitude respond so differently to treatment.

The only other rider he knows well, with a somewhat comparable long-term timescale for injury recovery, is Taylor Phinney (BMC), whose big crash and injuries stretch back to the 2014 US National Road Race Championships. Although Phinney raced periodically in 2015, he is only now starting his first full year back with BMC in Europe, making his own 2016 start at the Tour du Haut Var last weekend, finishing 57th.

“One thing I learned in the first part of my recovery is the virtue of patience,” Stetina said, “because when you’re first waiting for the bone to heal, it doesn’t matter how hard you push rehab. The bone still needs a minimum of three to four months to heal. That’s just a minimum. And now even though I’m racing, it’s the same thing, I’m doing everything as professionally as I can but you just have to let the process run its course.”

On a mental level, Stetina has found some unexpected bumps on his personal recovery roadmapl. Older riders often talk about how, with retirement on the horizon, they may well unconsciously brake earlier in bunch sprints, and Stetina says that although his added wariness does not necessarily show itself in the finishes, he has found himself feeling edgier than he expected in general about racing.

“I thought I was okay for the most part, and in the field I feel okay when it’s starting to fight, because my accident was so obscure and different, it’s not like it was a normal crash in a group. So I wasn’t scared [in the finishes]. But I realised during stage 2 of the Vuelta a Andalucia, when we went down that crazy wet descent into the finish in Cordoba, that - post the accident - I hadn’t done a downhill in the wet in Europe on a narrow road like that.

"I was putting on a lot of brakes there, I was pretty scared. The next day was a bit better but I need to get the pack skills back a little bit. It’s another case of just racing more and it’s already better this week that it was at the beginning. So it’s all a question of patience, but it’s to be expected, that’s all pretty standard.”

Rider Safety, more accountability

The crash itself in stage 1 of the 2015 Vuelta al Pais Vasco was caused by a series of metal poles in the finishing straight, which were given the scantest of indications - orange cones, placed on their tops like hats - of impending danger. The subsequent pile-up and list of injuries in the main bunch saw both Stetina and Spain’s Sergio Pardilla (Caja Rural-RGA) out for the season. In Pardilla’s case with a wounded hand that was, he said, “ripped apart in the crash”.

Adam Yates (Orica-GreenEdge) broke one of his fingers, half a dozen more riders were affected with lesser injuries, and the presence of the poles in such a risky location provoked a brief protest by the peloton the following day at the stage 2 start. The Vuelta al País Vasco management later recognised to a local newspaper that it “should have done more” to protect the peloton.

“The crash was inexcusable in my mind,” Stetina says. “I think organisers need to be held more accountable for the safety of their races, particularly in the finishes where it is more cut-throat, whether that’s the UCI being held to oversee that or another party such as the CPA Professional Riders Association. I know they are standing strong about it now.”

According to the UCI’s Organisers’ Guide to Road Events, published in 2013, after each UCI-classified road event, the President of the Commissaires’ Panel draws up a report, 13 pages long in total, which goes over all aspects of the race, including safety.

“In the event that serious failings are noted,” the Guide reads, “the organiser is sent a letter requesting these failings be rectified the following year. If this does not occur, the race is withdrawn from the international calendar.”

Yet is that enough? Stetina, for one, argues that more should be done.

“I see a big discrepancy when riders can be fined for littering or taking a sticky bottle or taking a piss at the wrong time,” he said. “We personally get a fine from the UCI, but the organisers do something that’s inexcusable and they don’t face any sanction. I see a discrepancy in that that I don’t like.”

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.