Rasmussen on micro-blood doping study: I told you so

Danish researchers show performance gains from 135ml autologous transfusion

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

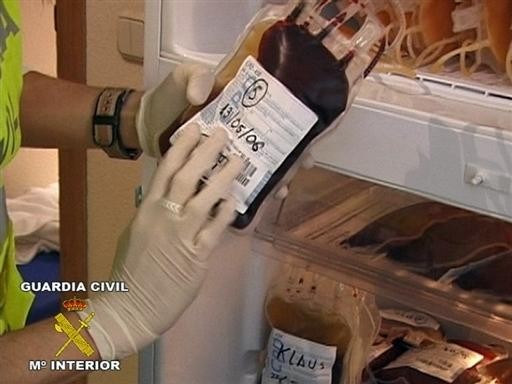

Danish researchers have published a study in which they demonstrate a five per cent increase in a cycling time trial effort after an infusion of just 135ml (4.5 ounces) of the subject's own packed red blood cells.

Fuentes recognizes 'some top sports names' could be owners of Puerto blood bags

Movistar suspend Roson after UCI open biological passport investigation

Spanish court authorises release of Operacion Puerto blood bags to Italian Olympic Committee

42-year-old Venezuelan rider Ubeto banned for biological passport violation

In his column on Ekstrabladet.dk, Michael Rasmussen reacted, "I told you so!".

"I said on TV 2 during the summer's Tour de France that it is largely possible to do what I did in my time as an active rider in the peloton today, to dope with your own blood without being detected," Rasmussen said.

It might be possible, but are riders really using these small volume transfusions?

Nikolai Baastrup Nordsborg, the principal researcher at the Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports at the University of Copenhagen, told Cyclingnews that the experiments by Bejder et al, the results of which were be published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, started with rumours that athletes were using this low volume method.

"This was talked about more than five years ago in the anti-doping environment," Baastrup Nordsborg said. "There were rumours about doctors advising athletes not to take too high dosages of blood because that would increase the risk of being caught. Based on those rumours - and they are rumours - then we started to think we need to be able to detect these small volumes.

"Do I think it's being used? Well, I have no chance of saying that, but I can say in a very general term that history has shown us to be naive if we don't expect people to do more or less everything that is possible.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"Until our study, the studies that had been done used one two, or even three bags of blood - and we know from history in cycling that some of the riders back in the 80s, they went even higher - with four, five, even six bags of blood.

"But in this study, we went the other way and said what happens if we give half a bag, and half a bag corresponds to 135 milliliters of what is termed packed red cells, so that is red cells without the plasma fraction in it."

Baastrup Nordsborg emphasised that they had considered the ethics of publishing a report that could be used as a roadmap for doping.

"We need to know what is the lower limit that we have to be able to detect. So if we don't do these kinds of experiments where we try to adjust the volume in small steps, then we simply don't know what the demands are on our sensitivity when we do anti-doping testing.

"It is an ethical consideration whether it should be made known to the public but I think it's more important especially in anti-doping, I think it's very important to be open and show the results that we have more than being reluctant to share knowledge and then just ignoring what might be going on."

The experiment

Anti-doping authorities have been able to detect blood transfusions between compatible people (homologous) for years - Tyler Hamilton and Alexandre Vinokourov were banned for this type of doping - so athletes have resorted to micro-dosing EPO or transfusing their own blood. It's why we know of Eufemiano Fuentes and Operacion Puerto.

Numerous studies have confirmed the performance benefit of an autologous transfusion of more than 800ml of whole blood, but experiments using lower volumes have not shown a consistent boost.

Bejder et al used nine test subjects, half of which had 900ml of whole blood removed (blood transfusion group/BT), while the other half had a fake blood draw (placebo, PLA).

Four weeks later, subjects were given either 135ml of packed red blood cells or saline for the placebo group. Two hours later they were asked to perform an exercise test that included a 650kcal time trial effort.

Three months later, the groups were reversed, with those who had previously had blood removed were now subject to the 'sham' blood draw and those who had not had blood drawn now had 900ml taken. Four weeks later, the subjects performed the same exercise study, but the group that most recently had blood removed was given the 135ml ABT.

The watts produced during the time trial efforts of each subject were then compared pre- and post-injection of saline or blood.

There was variability between the efforts for each person's 'sham' trial - researchers postulate this was due to the time trial efforts taking place four months apart. More importantly, the post-135ml ABT showed a statistically significant performance boost (P < 0.05) of approximately five per cent.

The study was very small - of the nine subjects, only seven completed the time trials. But Baastrup Norsborg says the design of the study (double-blind crossover) gives them confidence in the results.

"Every participant serves as his or her own control ... So that means that we have to have a very, very high confidence in the testing we see on the bike."

Considerations for anti-doping

While the study has its limitations - measures of VO2 Max and haemoglobin did not rise at the same rate as one might expect, and there was little further increase in performance after a larger blood transfusion, the paper serves as a platform for anti-doping researchers to step up efforts to develop new methods for ABTs.

"If you can get a five per cent increase in your performance from a low transfusion [and a high volume transfusion] then you have the same performance-enhancing effect, basically, from the two strategies," Baastrup Nordsborg said.

"And that's disturbing because if you can get the same performance-enhancing effect with a low volume as a high-volume then anti-doping-wise then we really have a problem."

The UCI (now the Cycling Anti-Doping Foundation - CADF) have used the biological passport for years to indirectly detect changes in blood values that could indicate a performance-enhancing transfusion. But Baastrup Norsborg admits it is possible that the passport would be less sensitive with lower-volume transfusions.

"We know from previous that when we reduce the volume of the transfusion, then the detection is becoming more and more difficult. And so we also expect this to be difficult, but we did not report those results in the manuscript, but we will certainly look into it."

Rasmussen, who admitted to using blood doping, EPO and other performance-enhancing methods during his career, put the study into perspective. "If you repeated the experiment with 20 Tour riders, you would get a more accurate picture of the power boost, but the fact is that blood doping works."

"Until there is a 100 per cent reliable blood doping test, there is no need to reinforce and maintain the illusion of pure sport."

Laura Weislo has been with Cyclingnews since 2006 after making a switch from a career in science. As Managing Editor, she coordinates coverage for North American events and global news. As former elite-level road racer who dabbled in cyclo-cross and track, Laura has a passion for all three disciplines. When not working she likes to go camping and explore lesser traveled roads, paths and gravel tracks. Laura specialises in covering doping, anti-doping, UCI governance and performing data analysis.