Plasticizers test moves towards validation

New test could prove a hugely useful tool for anti-doping investigators

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The validation of a test designed to detect plasticizers has moved a step forwards following the publication of a manuscript describing the method in a highly respected scientific journal.

The manuscript, published in the journal Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry in December, sets out how labs would be able to assess whether an autologous blood transfusion has taken place by detecting the presence of the metabolites of the plasticizers that are used to increase the flexibility of blood bags.

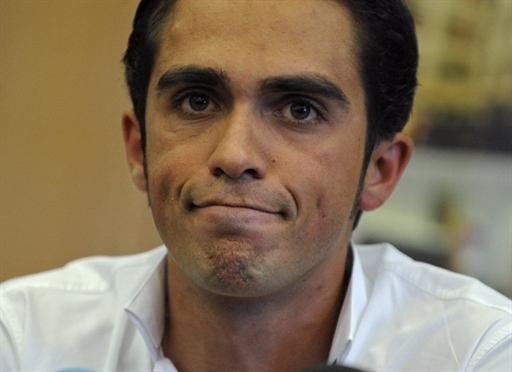

Today’s edition of Spain’s El País says the manuscript’s publication suggests a link to the doping investigation involving Alberto Contador, who tested positive for clenbuterol during the 2010 Tour de France. On 5 October, the New York Times reported that scientists at the laboratory in Cologne had detected the presence of plasticizers in the urine of the three-time Tour de France champion using a test that had not been validated.

According to El País, just two weeks after the publication of that story, 12 investigators at the labs in Cologne and Barcelona and the universities of Bochum and Budapest sent a manuscript detailing the test to Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. After subsequent revisions, the manuscript was accepted for publication in November.

An anonymous source described by El País as “close to the World Anti-Doping Agency’s scientific committee”, says of the rapidness of the manuscript’s publication: “The publication fits exactly with what WADA would describe as an article of validation, which is necessary for official endorsement of the use of a method by laboratories as an anti-doping test.”

The source added: “I can’t avoid the suspicion that all of this is related to the situation with Contador.”

Also contacted by El País, the director of Madrid’s anti-doping laboratory, Jesús Muñoz-Guerra, described the new method as “an important step in establishing the indirect detection of transfusions. Plasticizers are easy to find, but the difficulty lies in determining at what level the metabolites of a plasticizer signal the use of a transfusion because we can find plastics in everyone’s urine.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The authors of the paper have recognized this and have themselves stated that the method cannot be used as proof of doping, but is of use when applied in conjunction with other tests and with details available in a rider’s biological passport.

During the study, the scientists tested the urine of 10 patients who had undergone blood transfusions and 100 people in a control group. During a six-month period, 468 official urine controls were taken.

The results showed that the level of plasticizers in the urine of the 100 people in the control group remained below a fixed point, while the 10 people who had undergone transfusions recorded significantly higher levels. Strangely, three of the highest levels were recorded by three members of the same cycling team tested on the same day.

Peter Cossins has written about professional cycling since 1993 and is a contributing editor to Procycling. He is the author of The Monuments: The Grit and the Glory of Cycling's Greatest One-Day Races (Bloomsbury, March 2014) and has translated Christophe Bassons' autobiography, A Clean Break (Bloomsbury, July 2014).