Mercatone Uno wants 1999 Giro d'Italia awarded to Pantani

Gotti: "I'm prepared to give it up"

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

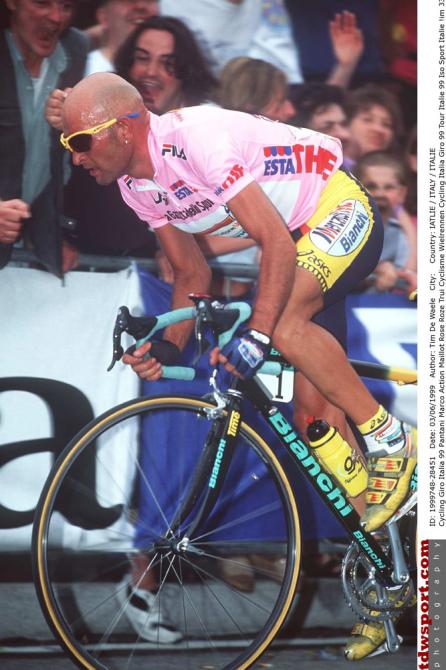

Mercatone Uno president Romano Cenni has hired a lawyer in a bid to have victory at the 1999 Giro d'Italia assigned to the late Marco Pantani. Cenni's legal action follows claims – 15 years old but recently re-aired extensively in the Italian press – of irregularities in the testing procedures when Pantani returned a high haematocrit on the penultimate day of that Giro and was forced out of the race while leading the overall standings.

Pantani spent seven years at the Mercatone Uno team, winning the Giro and Tour de France in their colours in 1998. The Italian supermarket withdrew from cycling sponsorship following the 2003 season, Pantani's final campaign.

"I can't say if it was a conspiracy, an error or something else, but what I am certain of is that new elements are emerging which show that the decision taken against Marco Pantani and the Mercatone Uno team should be modified and revised," lawyer Marco Baroncini told mediaset.it.

"Mercatone Uno and, in particular, its president Romano Cenni, just want for Pantani to be given what was taken unjustly from him and the team."

Pantani was almost six minutes clear at the head of the general classification of the 1999 Giro when he returned a haematocrit of 52% in a blood test at Madonna di Campiglio on the penultimate morning of the race, automatically triggering a two-week break from racing, as per the regulations of the time. The so-called "health tests" had been introduced in 1997 as a precursor to an approved control for EPO, and riders who recorded a haematocrit in excess of 50% were ordered to stop racing for two weeks to allow their blood values return below the limit.

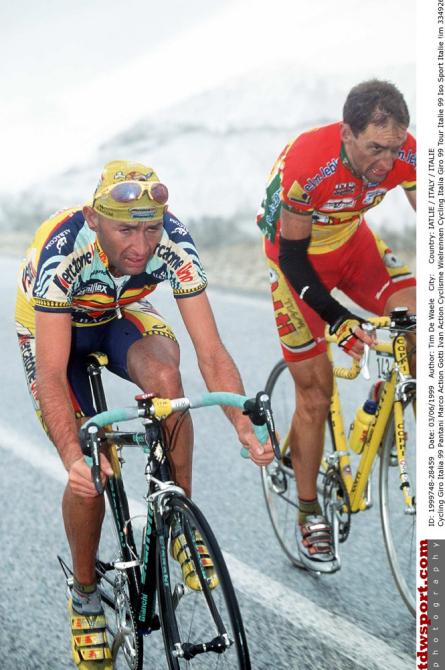

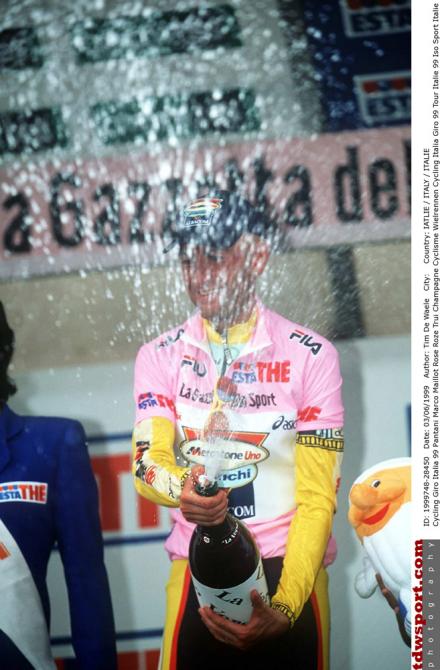

In Pantani's absence, Ivan Gotti overcame Paolo Savoldelli on the Mortirolo to move into the pink jersey and he went on to claim final overall victory in Milan the following day. It was Gotti's second Giro victory following his 1997 triumph, but it was wholly overshadowed by the furore that surrounded Pantani’s exclusion.

Speaking to Gazzetta dello Sport on Wednesday, Gotti said that he would have no objections if the 1999 Giro was taken from his palmares and posthumously awarded to Pantani, who died in 2004.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"Re-writing history isn't a problem relative to what happened to poor Marco," Gotti said. "If they were to award him that Giro, I wouldn't feel deprived of something. I'm prepared to give it up."

Mercatone Uno's lawyer Baroncini said that he wants the 1999 Giro's general classification to be returned to how it stood after stage 20 to Madonna di Campiglio, when Pantani led Savoldelli by 5:38 and Gotti by 6:12 with two days remaining. He claimed that a recent rallying event in Italy served as a precedent when the final three laps were disregarded after tacks placed on the road had caused the leading car to puncture.

A French Senate report last year revealed that a urine sample provided by Pantani during the 1998 Tour de France had been re-tested and shown traces of EPO, but then UCI president Pat McQuaid confirmed that the results of the race would not be altered retroactively. Along with second-placed Jan Ullrich, Pantani was one of 18 riders whose re-tested samples showed traces of EPO, while a further 12 were deemed to be "suspicious."

In recent months, magistrates in Italy have announced that they will re-examine both the circumstances surrounding Pantani's haematocrit test in 1999 and his untimely death in Rimini in 2004. In August, a lawyer acting on behalf of Pantani's parents submitted a dossier to magistrates in Rimini claiming that he had been murdered by being forced to drink a solution of water and cocaine.

Earlier this month, a magistrate in Forlì re-opened an inquiry into events at Madonna di Campiglio in 1999. It will look into an old allegation that Pantani's elevated haematocrit came about due to the influence of an illegal gambling ring, an accusation that was already made public in a book written some 15 years ago by the career criminal Renato Vallanzasca.