Genevieve Jeanson - Exclusive Podcast

Canadian details the abusive relationship that led to her career-long doping

Genevieve Jeanson’s face stood out amongst the crowds of people watching the UCI Road World Championships in Richmond, Virginia, in September. The French Canadian is one of the most controversial figures to have come out of women’s cycling after she confessed in 2007 to using erythropoietin (EPO) during most of her career, beginning as a teenager in 1998 and through her early 20s until 2005. She was subsequently issued a reduced 10-year ban for cooperating with an investigation conducted by the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) into her allegedly abusive coach Andre Aubut and Montreal-based physician Maurice Duquette.

Jeanson, now 34, sat down for an impromptu podcast discussion with Cyclingnews’ Kirsten Frattini, in what was her first English-speaking interview since her doping revelations. During the interview, Jeanson opened up about her relationship with Aubut and made serious allegations that prompted Cyclingnews to investigate further.

The process of establishing facts involved an extensive amount of research over the course of ten weeks. This included examining the history of Jeanson’s and Aubut’s coach-athlete relationship, their respective doping suspensions, following up with key sources and gathering statements to substantiate Jeanson’s allegations of abuse, which included a series of threats.

“Andre always told me that he was going to commit suicide if I left him and that he would kill me and then he would kill himself,” Jeanson told Cyclingnews in the podcast. “When I started taking EPO, he told me, ‘if you say that to anyone I’m going to kill you.’”

After the podcast discussion, Cyclingnews conducted four follow-up interviews with Jeanson, on September 28, October 1, October 31 and November 27, to establish timelines, and to develop a more complete understanding about her claims.

Cyclingnews also communicated with governing bodies such as the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) and Cycling Canada for additional information.

The follow-up interviews with Jeanson, along with interviews with her former teammates Catherine Marsal and Amy Moore, and Cycling Canada’s CEO Greg Mathieu will be published at a later date.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Continue reading the full feature story below and click here to subscribe to the Cyclingnews podcast.

It’s been eight years since Jeanson’s somewhat defiant confession about cheating while speaking with respected Canadian journalist Alain Gravel in his investigative report that aired on Enquête, a Radio-Canada television show, in September of 2007.

The French-language, two-part interview is now on Youtube, and English translations of part one and part two of the interview are available at Canadiancyclist.com.

Following her admission, Jeanson all but disappeared from the cycling community, only briefly resurfacing when a film that was loosely inspired by her story called Le Petite Reine was released last year.

Doping stories are common in the cycling press, but Jeanson’s story is far from the typical caught-and-suspended headline. Hers is an unsettling account that began back in 1994 about a 13-year-old girl who found her way into the sport of cycling and later became embroiled in an unhealthy and unethical relationship with her coach Aubut, who was in his forties. It was a relationship that she described to Cyclingnews as abusive, both verbally and physically.

It’s a story that provides the sporting world with lessons to be learned, delving deep into the fundamentals of ethics in sport concerning doping, a disturbing coach-athlete relationship, and a sweeping lack of moral responsibility at that time from the coach and doctor, the parents of a youth cyclist, and eventually the adult cyclist herself.

The Doping

Speaking with Cyclingnews in the podcast, Jeanson’s mannerisms bore almost no resemblance to that of the challenging 20-something-year-old from the Enquête television airing. She seemed more relaxed and spoke freely about cheating during her career, and provided a shocking recollection of her nearly 10-year relationship with Aubut.

She explained that she met Aubut during the summer of 1994. She had just gotten into cycling, and he was working as a high school teacher and in a local bike shop. The next year, when she was 14, and with the consent of her parents, Aubut designed cycling training programs for her to follow a few days a week.

Jeanson told Cyclingnews that she first took EPO in 1998 when she was a 16-year-old junior cyclist, and alleged that Aubut and Duquette, a local doctor, gave her the blood-boosting drug at an appointment that she attended with her father. But she continued to use the drug for eight years until she tested positive for it in 2005.

“The first time that I got it [EPO] it was because I was anaemic, so we brought in my parents, into the thought that, ‘well, your daughter is kind of sick and this is going to help her to continue sport. After that I just continued [to use EPO].

“It’s true that at first my parents, they knew that it [EPO] was a banned substance, and they knew that it would help me get back on my feet.”

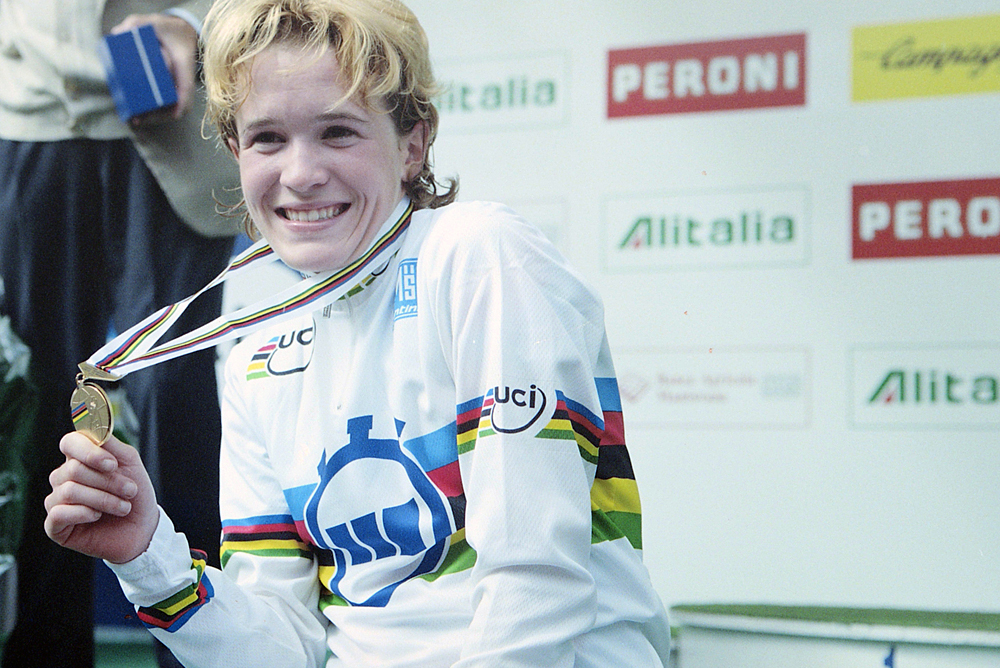

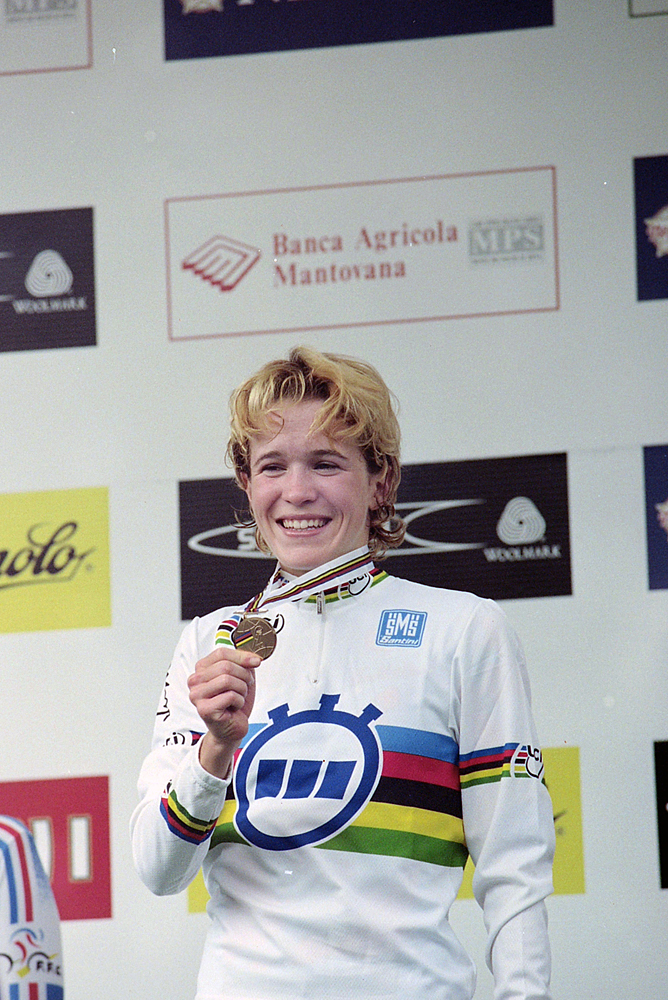

During her career, she won world titles in the junior road and time trial in 1999 and won La Flèche Wallonne Feminine World Cup the following year. She was on the Canadian team to compete in the women’s road race at the Sydney Olympics in 2000, alongside compatriots Clara Hughes and Lyne Bessette. She also won elite road titles in 2003 ahead of Bessette and Sue Palmer-Komar, and in 2005 ahead of Erinne Willock and Palmer-Komar.

On the US domestic racing scene, she won overall titles at the International Tour de Toona twice (2001 and 2005), Redlands Bicycle Classic twice (2001 and 2003) and Tour of the Gila three times (2001-2003), sometimes demolishing the peloton by a suspicious 10-plus minutes.

But some of the most questionable victories during her career were from the Montreal World Cup, which she won four times (2001, 2003-2005). And it was these performances that launched Jeanson into stardom in Montreal, and throughout Quebec and Canada.

There were multiple red flags during those years. For example, she was forced to sit out of the women’s road race at the 2003 World Championships because her blood test results showed an alarming 56 per cent haematocrit [above the 47 per cent safety threshold permitted for women under UCI rules, - Ed.], she missed a doping control at La Fleche Wallonne and she returned a positive test for EPO at the Tour de Toona in 2005.

The United States Anti-doping Agency (USADA) initially held jurisdiction over Jeanson’s failed doping test in 2005 because she was issued a racing licence in the US. They initially suggested she be given a lifetime ban. Jeanson denied using drugs and argued that there were problems with the World Anti-doping Agency’s urinary EPO tests at that time. In that process, she hired Belgian professor Joris Delanghe to review her case and he concluded that her positive test could have resulted from a severe case of exercised-induced proteinuria, which could trigger a false positive test result. Before her scheduled hearing, however, Jeanson accepted a settlement offer from USADA and her suggested lifetime ban was reduced to two years. She ended up retiring from the sport before the end of her suspension in 2007.

Over a long and drawn out process, Jeanson eventually confessed to doping in the Enquête interview in 2007, after which CCES launched a 12-month investigation into her, Aubut and Duquette. As a result, she received a lifetime ban for repeatedly using EPO during her cycling career, which was then reduced to ten years for providing CCES with “ready assistance in establishing anti-doping rule violations against her physician [Maurice Duquette] and coach [Andre Aubut].”

Jeanson’s sanction period ends on September 20, 2017. She was not stripped of the majority of her racing results.

CCES handed Duquette a lifetime ban for the “administration of a prohibited substance to a minor (Ms. Genevieve Jeanson) and that he assisted, aided and abetted in the administration of a prohibited substance, namely erythropoietin (EPO).” Duquette acknowledged the violation and waived his right to a hearing.

CCES also handed Aubut a lifetime ban following its investigation for, “administering a prohibited substance, erythropoietin (EPO), to Genevieve Jeanson during her cycling career.”

Arbitrator Michel G. Picher stated in his decision at that time that “Since this anti-doping rule violation by Mr. Aubut involves in particular the administration of prohibited substances to a minor, the Arbitrator orders that the sanction for this violation be Lifetime ineligibility in accordance with Rule 7.36…”

Aubut exercised his right to proceed to a hearing, however, the panel later determined that Aubut had violated the provisions of the Canadian Anti-doping Program.

Aubut and Duquette remain the only two lifetime suspensions handed to people, other than athletes, in Canadian Anti-Doping Program.

[According to the Enquête interview, Aubut refuted allegations that he pushed Jeanson into using EPO, - Ed.]

Cyclingnews asked Jeanson, in a follow-up interview, why she finally decided to come clean in 2007, particularly after years of denial, lies and cover-ups about her use of EPO.

Jeanson replied, “I saw it as my chance to tell the truth because I didn’t know if I would ever be asked again to do an interview. With Alain, it was a very long process, he came to Phoenix about six times, and we had a chance to talk, I got to know him, I felt comfortable. I needed just to say it – for the kids that I might have one day, for getting rid of all my baggage and for healing. I couldn’t carry all that around anymore.”

Although Jeanson has confessed to doping during her career, she hasn’t made a formal or public apology to the cycling community and has not offered to return her titles or prize money. According to Cycling Canada CEO Greg Mathieu, members of the cycling community would welcome such gestures.

“I can tell you that there are an entire group of athletes out there that are still waiting for that [an apology],” Mathieu told Cyclingnews.

“She has never admitted to using drugs at specific events. If she wants to turn back her championships and turn back her prize money, there are probably a lot of people who would welcome it.

“You have one group of people who feel this athlete cheated and took away things from clean athletes, took away positions on teams, took away podiums, took away prize money. Then you have another group of people who would say, ‘look at the position she was in; she had no guidance or support, she got attached to this person [Aubut] at a very young age and didn’t know anything else’. There are people who have empathy for the situation.”

When Cyclingnews asked Jeanson if she has ever considered returning her titles and making a public apology, as a gesture to the cycling community, she hesitated and then replied, “I have never thought about it [returning titles and apologizing] because I was always too caught up in the only world that I knew. I would have to really ask myself this question. I am sorry for everything that I created and to everybody that I hurt.

“I’m going through a process of being more authentic and I have so many layers of stuff; of shit, of emotion, of traumatic events, of good events, or praise and criticism, and all that stuff. The only way I can get to the core of it is to take one layer off slowly, at a time.”

Cyclingnews asked Jeanson if she ever felt remorseful for cheating, to which she answered, “I feel remorseful for all my fellow cyclists and fans that I hurt through my actions and bad decisions. But even with EPO I put a whole lot of effort, dedication and passion into what I was doing.

“When you are in the situation, you try to convince yourself that you are doing the right thing. At some point, it became my normal. I didn’t think about that [remorse] at the time because it made me feel… I didn’t want to deal with it.

“Do I feel remorse now? Oh, that’s a good question. I do feel bad… Yes, I feel bad sometimes. I feel bad sometimes, but it was my reality.”

Aubut, and the allegations of abuse

Jeanson told Cyclingnews in the podcast interview that she feared Aubut early on in their coach-athlete relationship, even when she was as young as 15.

She alleges that Aubut threatened to kill her and then commit suicide if she told anyone about taking EPO or if she ever left him and that he beat her up, gave her a black eye, that he abused her, screamed at, and that he threw things at her.

Cyclingnews obtained a statement from an individual who wished to remain anonymous, but who lived in proximity to Jeanson and Aubut that reads, “She [Jeanson] was very shy and scared with him [Aubut]. At that time she always had black and blue here and there, I’d ask about it, but she would brush it off, saying that she fell or something. Once or twice, I asked her what it was but she kind of brushed it off like she didn’t want to talk about it and I didn’t want to be invasive.”

Cyclingnews asked Jeanson if she ever called authorities, reached out for help or told anyone about the physical abuse. She replied, “I never did. For a long time, I was afraid that he would come after me. And after that, I started to live my life, and I didn’t want to deal with it anymore. The only thing that I wanted to deal with was my own shit, and how I could live and how I could get through with it.”

Aubut did not respond to Cyclingnews’ phone messages or a letter mailed to his address seeking a comment concerning Jeanson’s allegations of verbal and physical abuse.

Jeanson’s allegations are not new. After the Enquête interview aired in 2007, Gravel wrote L’affaire Jeanson: l’engrenage, a book that documented his interview process with Jeanson, and the steps in took for her to open up about her history with doping. It also detailed the unhealthy relationship between Jeanson and Aubut.

In his book, Gravel noted Jeanson’s allegations of abuse. She told him that Aubut punched her in the face because he was not happy with her training (p. 75 and p. 81). That he hit her several times (p. 175), and that he was physically violent (p. 81, p. 108, p. 178 and p. 184). She gave two specific examples of violence: a punch in the face that resulted in a black eye during a training ride in Arizona in 2004 (p. 218) and a violent episode in a hotel bathroom in Italy in 2004 (p. 185). She noted that she told no one about the abuse, but several people saw the black eye and that she made up a story to explain why she was bruised to keep the violence a secret (p. 185).

Gravel spoke with two witnesses who saw the black eye. Jeff Kurtz, a coach who frequently rode with Jeanson, said she gave him an excuse about hitting her head on a car door but that he knew it was a lie. And an anonymous person who refused to speculate how she got the black eye (p.189).

When questioned by Gravel, Aubut refuted all of Jeanson’s allegations of abuse and the threats to kill himself if she left him. He said that he was aggressive but no more so than any other trainer with a temper. He claimed that Jeanson’s black eye was from hitting her head on a gym bar (p. 222 and p. 230).

Aubut also claimed that Jeanson made up the allegations of abuse because she was frustrated at not being able to compete and because he had said he would not be her coach anymore. (p. 235).

Gravel spoke with Jeanson’s former teammates; Amy Moore, Catherine Marsal and Magali Le Floch, who recalled Aubut’s controlling nature and verbal abuse toward Jeanson. They also reported seeing him throw objects at her after bike races.

Cyclingnews also spoke with Jeanson’s former teammates Marsal and Moore, along with Aubut’s former co-director at Rona Jim Williams. All three witnessed Aubut’s verbal abuse toward Jeanson and saw him throw objects at her, however, they did not see other forms of physical abuse such as hitting or punching.

Cyclingnews obtained a statement from Marsal, who was contracted to race for the Rona team in 2003, in which she described her experiences with Aubut and Jeanson during that year.

“Verbal abuse was pretty constant. He [Aubut] was rough with her [Jeanson]. To put a hand on her, that I have never seen, but I have seen him throw a race radio at her from 5 or 10 metres away, being pretty mad at her for not performing in a race the way that he wanted.

“I can’t remember which race, but it was at the end of the season that I tried to reach out to Genevieve. I said, ‘Genevieve, this is not OK that a guy can talk to you like this.' And she sort of showed a blink of reaching out towards me… towards, [saying] ‘yeah, I know it’s hard but that’s the way that it is, I know I need help’ or ‘I don’t know how to get out of this.' But as soon as he [Aubut] came back, he took back the control of her.

“We should detach ourselves from cycling because this [story] is a human thing, it’s really bad on a psychological level, it’s an abuse of coach-coachee that goes way beyond the story of doping.”

Moore also described to Cyclingnews her experiences on the Rona team in 2001 and 2002, under the direction of Aubut, and as a member of the Canadian national team in 2003, where she was also teammates with Jeanson.

“Yes, that was a constant,” Moore said when asked if she had ever witnessed Aubut verbally abuse Jeanson.

She also described witnessing Aubut throw a dinner plate at Jeanson for not eating enough. “He just lost it and went across the room. He picked up her plate and threw it at her,” said Moore, who briefly stayed at their rented townhouse while training in Arizona.

“We all know that ... she had been brainwashed from a very young age,” Moore said. “She was so unbelievably loyal to him. He could have done anything to her, and she would have stayed with him, especially from that young age, and because of the success that they built together.

“It’s just a sad case all around. Genevieve was an incredibly talented athlete, and it’s too bad that that is the path that she took. Who knows what she would have done on her own.”

Jeanson told Cyclingnews that she and Aubut were advised by their immigration lawyer to marry in April 2006 to purchase the restaurant they eventually owned together in Arizona. Their marriage, however, ended in divorce six months later.

In the Cyclingnews podcast discussion, Jeanson described the night she told Aubut that she was leaving him. It was at their restaurant. She said that she was afraid and alleged that he screamed and yelled at her, threw objects at her from across the restaurant and threatened to burn it down.

Cyclingnews collected a statement from an individual who was in the restaurant when Jeanson told Aubut she was leaving him. The individual wished to remain anonymous, but said, “I can’t remember exactly what he said, but he did yell and scream at her, and threaten her, and threaten me. He very calmly took a bottle of something – I don’t know if it was ketchup or mustard – and he threw it right across the restaurant at our heads.”

Aubut did not respond to Cyclingnews’ phone messages or a letter mailed to his address seeking a comment concerning Jeanson’s allegations that he threw objects at her and threatened to burn down their restaurant.

Jeanson has since sold her investment in the restaurant in Arizona. After her doping confession in 2007, she spent some time in San Diego, California, before returning to Montreal in 2012.

Jeanson told Cyclingnews that she and her parents had a falling out in 2006 but that since returning to Montreal, she has reconciled with them. She alleges that they knew about the initial EPO use in 1998, but that they did not know about the violence later on.

“I had to go back to Montreal and close all my loops there,” Jeanson said. “You know, face the music and face my parents, face that country that I love. You know and the Quebec people and Montreal… I had to face all that.

“We [Jeanson and her parents] got quite angry with each other in 2006 and 2007 so it took five or six years. But absolutely, I have forgiven them 100 per cent. My relationship with my parents [now] is great. I love them.”

Jeanson is currently a student of Neuroscience at Concordia University in Montreal, and she has continued part-time work in the restaurant business. She said that she has spent nearly a decade in therapy.

“I started to do therapy, and I’m still doing it,” she said. “I mean it’s been how many years now? Nine years that I’ve been in therapy. At the same time, [I feel like] I’m still on my own little island… but my life is OK now.”

For more information and educational tools about ethics in sport:

Cycling Canada: http://www.cyclingcanada.ca

-Race Clean Program - http://www.cyclingcanada.ca/resources/race-clean/canadian-centre-for-ethics-in-sport-cces/

Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport: http://cces.ca

-Canadian Anti-Doping Program – http://cces.ca/canadian-anti-doping-program

-The Prohibited List: http://cces.ca/prohibited-list

-Report doping: http://cces.ca/reportdoping

-Canadian Strategy for Ethical Conduct in Sport - http://cces.ca/ethical-issues

-Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport Online Education http://cces.ca/education-and-e-learning

-Appearance- and Performance-Enhancing Drugs (APEDs) and Youth: http://cces.ca/summit-apeds-and-youth

-Violence: http://cces.ca/violence

-Harassment and Abuse: http://cces.ca/harassment-and-abuse

-Physical Punishment: http://cces.ca/physical-punishment

-Poor Parental Behaviour: http://cces.ca/poor-parental-behaviour

-Negative Behaviours in Pro Sports: http://cces.ca/negative-behaviours-pro-sport

USA Cycling: https://www.usacycling.org

-Health and Anti-Doping - https://www.usacycling.org/health-anti-doping.htm

-Race Clean Program: https://www.usacycling.org/usa-cycling-raceclean-program.htm

US Anti-Doping Agency: http://www.usada.org

-Spirit of Sport: http://www.usada.org/resources/spirit-of-sport/

-Coaching Resources: http://www.usada.org/resources/coach/

-Health Professional Resources: http://www.usada.org/resources/healthpro/

International Cycling Union: http://www.uci.ch

-Clean Sport: http://www.usada.org/resources/healthpro/

-Health Ensure Cycling is Clean: http://www.uci.ch/clean-sport/help-ensure-cycling-clean/

-Education: http://www.uci.ch/clean-sport/education/

World Anti-Doping Agency: https://www.wada-ama.org

-Athlete Learning Program about Health and Anti-Doping (ALPHA): https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/education-awareness/tools-for-stakeholders/alpha

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.