Doubts raised over effectiveness of UCI tests for mechanical doping

Tablet device analysed by reporters from Il Corriere della Sera, France 2 and ARD

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fresh doubts have been cast upon the effectiveness of the UCI's testing for mechanical doping after reporters from Il Corriere della Sera, France 2 and German television station ARD had one of the governing body’s tablet scanners analysed at a laboratory in Germany.

The UCI has been using tablets to test bikes since 2016, and demonstrated the technology at a presentation in Aigle, Switzerland, in May 2016, where it was claimed that the device could detect magnetic flux density of hidden motors or magnetic wheels.

The UCI is estimated to have carried out 42,500 tests using its tablet over the past two years, but the device has yet to uncover any instance of mechanical doping. The governing body has encouraged national federations to purchase the device.

Il Corriere della Sera managed to procure one of the UCI scanners, and found that it consisted of an Apple iPad mini equipped with a magnet that serves as an antenna, as well as software developed by a company called Endoscope-i, based in Birmingham. The products listed on the British company's website are iPhone adapters for use in ear, nose and throat endoscopy.

Il Corriere, France 2 and ARD brought the device to the Fraunhofer Institute for Nondestructive Testing in Saarbrucken, Germany, where vice-director Bernd Valeske gauged its efficacy.

Valeske first used the tablet to scan a bike equipped with a rudimentary motor of the kind discovered in the bike of Femke Van Den Driessche at the 2016 Cyclo-cross World Championships. Van Den Driessche is to date the only rider to have been sanctioned for mechanical doping – or technological fraud, as the UCI prefers it to be called.

While the UCI tablet duly detected the magnetic field around the hidden motor, it also detected similar magnetic fields in three other places on the bike where there was no hidden motor. Such 'false positives' would ordinarily call for the dismantling of the bike for further inspection, but one WorldTour mechanic told Il Corriere della Sera that he has never seen UCI testers do anything more than swipe an iPad against the bikes in his care.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"We must have undergone over 2,000 tests, and not once have the inspectors asked for a second test or for a bike to be taken apart for further inspection," the mechanic said.

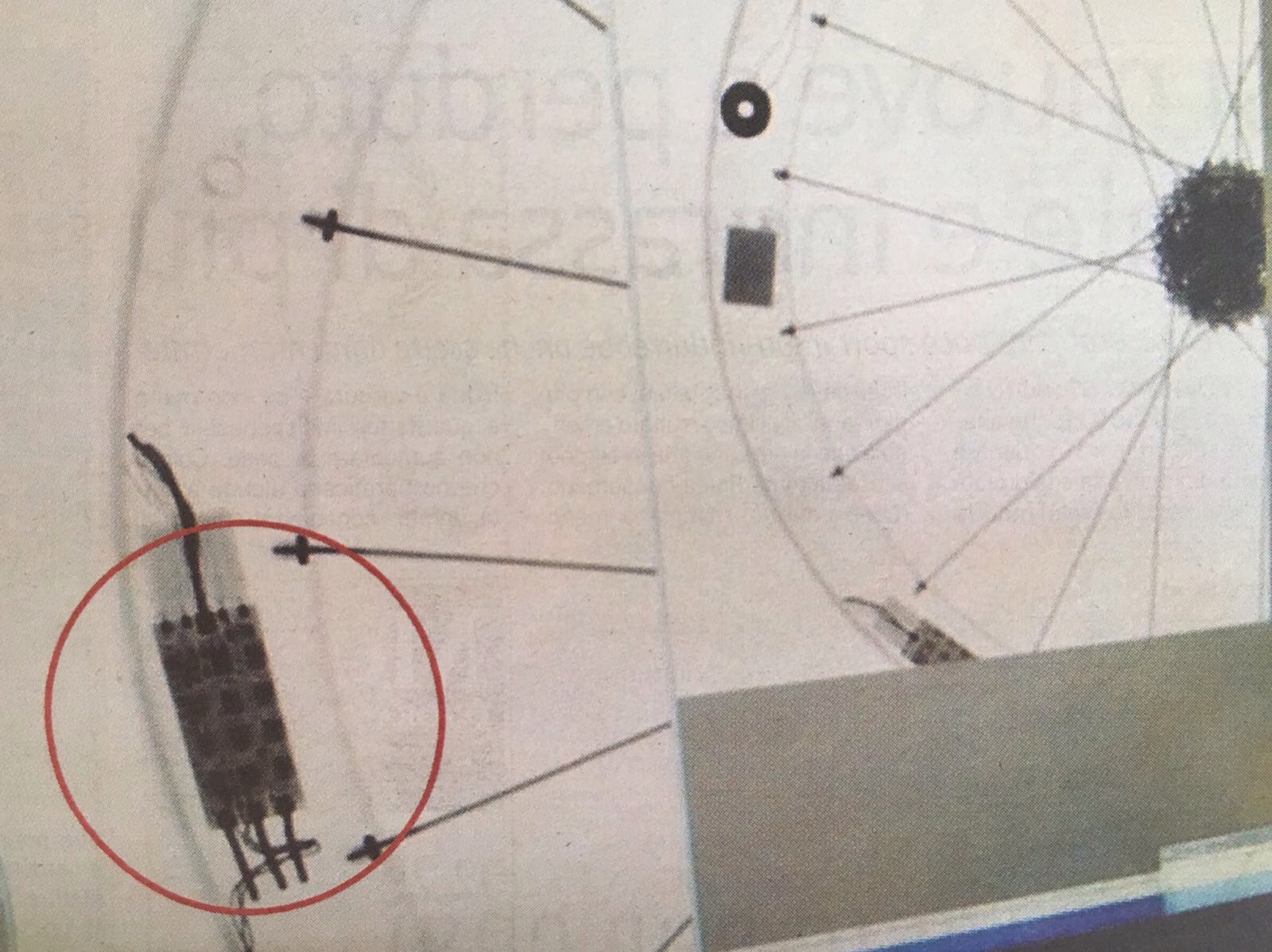

Valeske and his team proceeded to use the UCI tablet device to scan a bike equipped with an electromagnetic induction wheel. This is reputedly the latest generation of mechanical doping, and a wheel equipped with the technology is reported to cost over €20,000. The tablet failed to detect any magnetic field whatsoever around the wheel, but when the wheel was passed through an X-ray scanner, the induction motor was clearly visible.

"The wheel is 'perfectly clean', at least for the tablet. However, the X-rays instead show the induction plates and the transmission cables, perfectly hidden by carbon," wrote Marco Bonarrigo of Il Corriere della Sera. "The wheel that transforms the bike into a motorbike is, for the UCI controls, a piece of inert fibre."

The article in Il Corriere precedes Sunday afternoon's edition of the Stade 2 magazine show on France 2, which will include a report on the investigation and will feature footage from the testing at the Fraunhofer Institute.

The French television programme has reported extensively on mechanical doping in recent years. In June 2016, Stade 2 reported that UCI technical director Mark Barfield had alerted Harry Gibbings of the e-bike manufacturer Typhoon about a police investigation into the use of hidden motors on the 2015 Tour de France. The UCI said that it had "full confidence in its staff employed in this area" and Barfield remains in place as technical director.

David Lappartient, who is challenging Brian Cookson at this month's UCI presidential election in Bergen, has pledged to improve testing for technological fraud by using X-ray scanners and thermal cameras, and by disassembling bikes to allow for more thorough testing.