Cycling community would welcome apology, returned titles from Jeanson, says Cycling Canada CEO

Mathieu stresses importance of educating youth athletes and parents on sports ethics

Former Canadian cyclist Genevieve Jeanson’s doping file landed on Greg Mathieu’s desk in 2009, during his first year on the job as Chief Executive Officer of Cycling Canada [then called the Canadian Cycling Association] – and it was an eye-opener. But it also provided the cycling community with lessons to be learned about cheating, unhealthy coach-athlete relationships, and the need for youth athletes and their parents to educate themselves on the ethics of sports.

The Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) had just ended a 12-month investigation, prompted by Jeanson’s confession to using EPO during a 2007 interview with Canadian journalist Alain Gravel in his investigative report that aired on Enquête, a Radio-Canada television show. The investigation surrounded her coach Andre Aubut and her physician Maurice Duquette.

“Before I came on board, I had no knowledge of it,” Mathieu told Cyclingnews. “When I came on board I inherited the doping file and the issues and realities that went with it. There was a suspension for Genevieve, and a lifetime suspension to the coach and a lifetime suspension to the doctor, both of which remain in the Canadian Anti-doping Program (CADP) as the only lifetime suspensions ever given to people other than the athletes.”

Jeanson was initially given a lifetime ban for admitting to taking the banned blood booster EPO beginning as a 16-year-old in 1998 until she was caught for it in 2005 at the US stage race Tour de Toona. [Jeanson initially severed a two-year suspension from the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) from 2005-2007, - Ed.]. CCES reduced her lifetime ban to 10 years because she provided assistance in the investigation into her coach Aubut and doctor Duquette.

Jeanson’s sanction period began on September 20, 2007 and ends on September 20, 2017.

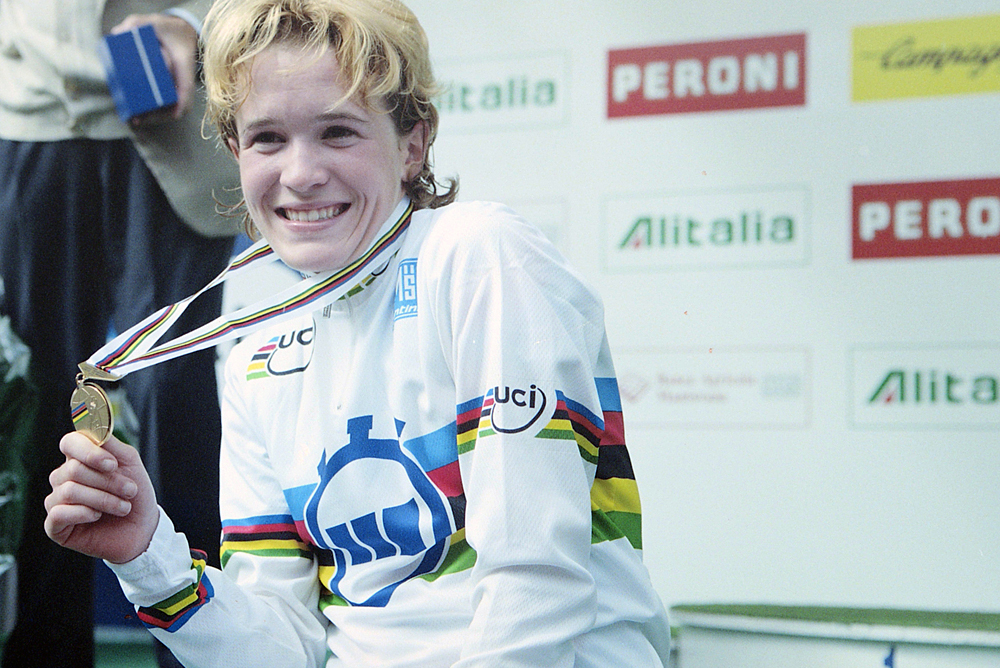

Jeanson’s controversial career included world titles in the junior road and time trial in 1999 and won La Flèche Wallonne Feminine World Cup the following year. She went to the Sydney Olympics in 2000 and won elite national road titles in 2003 and 2005. She also won the Montreal World Cup on four occasions and top-level stage races in the US; Tour de Toona, Redlands Bicycle Classic and Tour of the Gila.

The cycling community was suspicious; after all, she was forced to sit out of the women’s road race at the 2003 World Championships because her blood test results showed a 56 per cent haematocrit [above the 47 per cent permitted under UCI rules, - Ed.] and she missed a doping control at La Fleche Wallonne.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Read the full feature and listen to the Genevieve Jeanson: Exclusive Podcast.To read the follow-up interviews with Jeanson, click here. subscribe to the Cyclingnews podcast.

Despite admitting to using EPO for the majority of her career, sport governing bodies have not stripped her of most of her titles. CCES told Cyclingnews that it is the responsibility of the sport, for example, Cycling Canada or the UCI if it's international, to take titles away from an athlete where applicable.

The UCI did not immediately respond to Cyclingnews request for further information regarding Jeanson's titles before publishing this report. However, according to Mathieu, her titles weren't taken away because her ban was based on non-analytical findings.

CCES published Jeanson’s sanction on its website in April of 2009, which noted that its “investigation into the role of athlete support personnel is the first conducted by the CCES within the new World Anti-Doping Code’s focus on non-analytical methods of rooting out doping. Under the rules of the Canadian Anti-Doping Program, the CCES has the authority and the responsibility to investigate any allegations or evidence of anti-doping rule violations committed by athletes and athlete support personnel.”

According to Mathieu, although Jeanson admitted to using a EPO during her career, she never actually admitted to using it at or for specific events, and that was the reason the sports governing body could not take her titles from her. He went on to explain the the specifics of CCES's non-analytical finding in Jeanson's case.

“When the CCES made the finding through the case process that they had to go through, national sporting organisations are not involved in that, we are kind of positioned in the query, but we are not involved in the finding. The finding that was made for Jeanson was never one that said she used it [a banned substance] from this period to this period, or on this date or at this event, so there’s never been a finding that says at this specific event she was under the use of a prohibited substance.

"You can’t just assume that [she used a banned substance at specific events] because it's what’s called a non-analytical finding. That means that unless she admits that, ‘at the 2002 Canadian Road Championships I was under the influence of it,’ unless she says that, we can’t assume that. There is no analysis that backs us up asserting that, and she knows that, and we’ve had that discussion by email.”

Mathieu noted that there are members of the cycling community and her former competitors who felt, and still feel, cheated and angry because she continues to hold the top ranking at past international events.

“She has never, in my view, ever apologized to the people that she should probably apologise to,” Mathieu told Cyclingnews. “She never apologized to the other athletes that she took something from; I can tell you that there are an entire group of athletes out there that are still waiting for that.

“If she wants to turn back her championships and turn back her prize money, there are probably a lot of people who would welcome it.”

When Cyclingnews asked Jeanson if she has ever considered returning her titles and making a public apology, as a gesture to the cycling community, she hesitated and then replied, “I have never thought about it [returning titles and apologizing] because I was always too caught up in the only world that I knew. I would have to really ask myself this question. I am sorry for everything that I created and to everybody that I hurt."

"Jeanson’s coach-athlete dependency was preyed on by her coach," says Mathieu

Jeanson’s history with doping in cycling is just one side of her story. The other is one that involved a coach-athlete relationship with Aubut that developed at the young age of 14. It was a relationship that Jeanson described to Cyclingnews in an exclusive podcast as abusive, both verbally and physically. Her story also involves her physician doctor Duquette. CCES handed Aubut and Duquette lifetime bans for administering EPO to Jeanson when she was 16 years old, a junior cyclist.

"You have one group of people who feel this athlete cheated and took away things from clean athletes, took away positions on teams, took away podiums and took away prize money,” Mathieu said. “Then you have another group of people who say, ‘look at the position she was in,’ she had no guidance or support, she got attached to this person at a very young age and didn’t know anything else. There are people who have empathy for the situation.

“There was a co-existence [with her coach Andre Aubut] that was created from a young age and that coach-athlete dependency was preyed on by her coach.”

Mathieu expressed a strict view on the subject of Jeanson’s controversial career, her confession to cheating, and to the degree of her sanction and punishment, but he doesn’t undervalue her cooperation in the investigation that CCES conducted into Aubut and Duquette.

“In this particular case, we sought out and got substantial cooperation from Genevieve to find out where, how she was supplied [with EPO] and the circumstance around that. Then she gave them [CCES] enough investigative power to levy the finding that both the doctor and the coach be suspended for life, so that’s as heavy as it could possibly get in terms of a load that a young woman would have to carry on her own behalf,” Mathieu said.

In a published statement about Jeanson's suspension at that time, Paul Melia, President and CEO of the CCES said, “We have a duty to protect athletes’ right to a sport experience that is free from the pressure to dope exerted by individuals in positions of authority over athletes.

"This athlete’s admission to long-time use of EPO became a powerful tool to remove two influential members of her support team from the sport system.”

CCES gave Duquette a lifetime sanction for the “administration of a prohibited substance to a minor (Ms. Genevieve Jeanson) and that he assisted, aided and abetted in the administration of a prohibited substance, namely erythropoietin (EPO).”

CCES sentenced Aubut to a lifetime ban for “administering a prohibited substance, erythropoietin (EPO), to Genevieve Jeanson during her cycling career.”

In addition, Arbitrator Michel G. Picher stated in his decision at that time that “…Mr. Aubut committed an anti-doping rule violation pursuant to Rule 7.35 of the Doping Violations and Consequences Rules. He directly administered a prohibited substance, erythropoietin (EPO), to Ms. Jeanson while he was her coach. Moreover, the Arbitrator must conclude that Mr. Aubut aided, abetted and assisted in the administration of prohibited substances to Ms. Jeanson, also during the time that he was her coach.

“Since this anti-doping rule violation by Mr. Aubut involves in particular the administration of prohibited substances to a minor, the Arbitrator orders that the sanction for this violation be Lifetime ineligibility in accordance with Rule 7.36…”

Educational tools attempt to "inoculate" youth athletes from making wrong choices

In reference to the unhealthy coach-relationship between Aubut and Jeanson that began when she was a teenager, Mathieu stressed the importance for parents of youth athletes to educate themselves about the appropriate dynamics of a coach-athlete relationship, so that they can make informed decisions on behalf of their children.

He suggests parents seek out certified coaches (rather than personal coaches) who are trained under the principals of the National Coaching Certification Program (NCCP) and Coaches of Canada. These coaches sign up and agree to abide by the Coaches of Canada’s code of conduct. Nowadays, certified coaches are also vetted before being hired, and steps are taken to secure police records and background checks.

“There is a dynamic that occurs between a national coaching staff and personal coaches, and for a variety of reasons athletes and their parents choose to go one route rather than the other. Our sense is that the people we hire as national coaches are certified, members of Coaches of Canada. They understand the ethical basis of the sport, they understand the expectation that the national body has of them, and they carry out their duties in an appropriate way, they act in the best interest of the athlete.

“In our view, and in the view of our provincial and territorial affiliates, the key here is to make sure that the athletes and the parents seek out certified coaches. These are the people who have had the training, the background and the sensitivity to the issue of why people could perceive some things in an athlete-coach dynamic as being damaging or inappropriate.”

Mathieu stressed that coaches, parents and athletes who witness unethical practices between a coach and an athlete, including doping and abuse should report to the head coach of their club. If they feel that that is where the problem is than they should report to their provincial or territorial association.

“If it has to do with a higher level athlete, the report should advance to Cycling Canada, to any official as part of our organisation, because we are responsible for following up on those types of things when they are brought to our attention.”

Mathieu said that one of the lessons that we can learn from Jeanson’s story is to make sure youth athletes are well informed about the ethics of sport and coach-athlete relationships early on so that they can recognise for themselves a potentially unhealthy environment and alert authorities.

“Whether it’s education regarding ethical and value-based or participation, or what we call anti-doping, when you add education to it, you try to inoculate young athletes against going the wrong way, from making wrong choices.”

For more information and educational tools about ethics in sport

Cycling Canada: http://www.cyclingcanada.ca

-Race Clean Program - http://www.cyclingcanada.ca/resources/race-clean/canadian-centre-for-ethics-in-sport-cces/

Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport: http://cces.ca

-Canadian Anti-Doping Program - http://cces.ca/canadian-anti-doping-program

-The Prohibited List - http://cces.ca/prohibited-list

-Report doping - http://cces.ca/reportdoping

-Canadian Strategy for Ethical Conduct in Sport - http://cces.ca/ethical-issues

-Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport Online Education - http://cces.ca/education-and-e-learning

-Appearance- and Performance-Enhancing Drugs (APEDs) and Youth - http://cces.ca/summit-apeds-and-youth

-Violence - http://cces.ca/violence

-Harassment and Abuse - http://cces.ca/harassment-and-abuse

-Physical Punishment - http://cces.ca/physical-punishment

-Poor Parental Behaviour - http://cces.ca/poor-parental-behaviour

-Negative Behaviours in Pro Sports - http://cces.ca/negative-behaviours-pro-sport

USA Cycling: https://www.usacycling.org

-Health and Anti-Doping - https://www.usacycling.org/health-anti-doping.htm

-Race Clean Program - https://www.usacycling.org/usa-cycling-raceclean-program.htm

US Anti-Doping Agency: http://www.usada.org

-Spirit of Sport - http://www.usada.org/resources/spirit-of-sport/

-Coaching Resources - http://www.usada.org/resources/coach/

-Health Professional Resources - http://www.usada.org/resources/healthpro/

International Cycling Union: http://www.uci.ch

-Clean Sport - http://www.usada.org/resources/healthpro/

-Health Ensure Cycling is Clean - http://www.uci.ch/clean-sport/help-ensure-cycling-clean/

-Education - http://www.uci.ch/clean-sport/education/

World Anti-Doping Agency: https://www.wada-ama.org

-Athlete Learning Program about Health and Anti-Doping (ALPHA) - https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/education-awareness/tools-for-stakeholders/alpha

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.