CIRC uncovers serious weaknesses in UCI anti-doping strategy

Riders now able to cheat and stay below the Biological Passport radar

The CIRC report looks closely at the UCI's anti-doping programme and procedures, dedicating 100 pages of the 277-page report to the subject.

UCI to publish CIRC report on Monday

Riis and Vinokourov among 174 people interviewed by CIRC

CIRC: No new doping admissions or proof of corruption in UCI

CIRC suggests that doping has gone underground with micro-dosing and TUE abuse

CIRC: Contador given favourable treatment by UCI after 2010 Tour de France doping positive

The report suggests that for a long time, and especially up to 2006, when Anne Gripper arrived, the UCI's anti-doping strategy was "directed against the abuse of doping substances rather than the use of them," with "only the visible tip of the iceberg tackled. Deterrence was not an integral part of the strategy." It later states: "The emphasis of UCI's anti-doping policy was, therefore, to give the impression that UCI was tough on doping rather than actually being good at anti-doping."

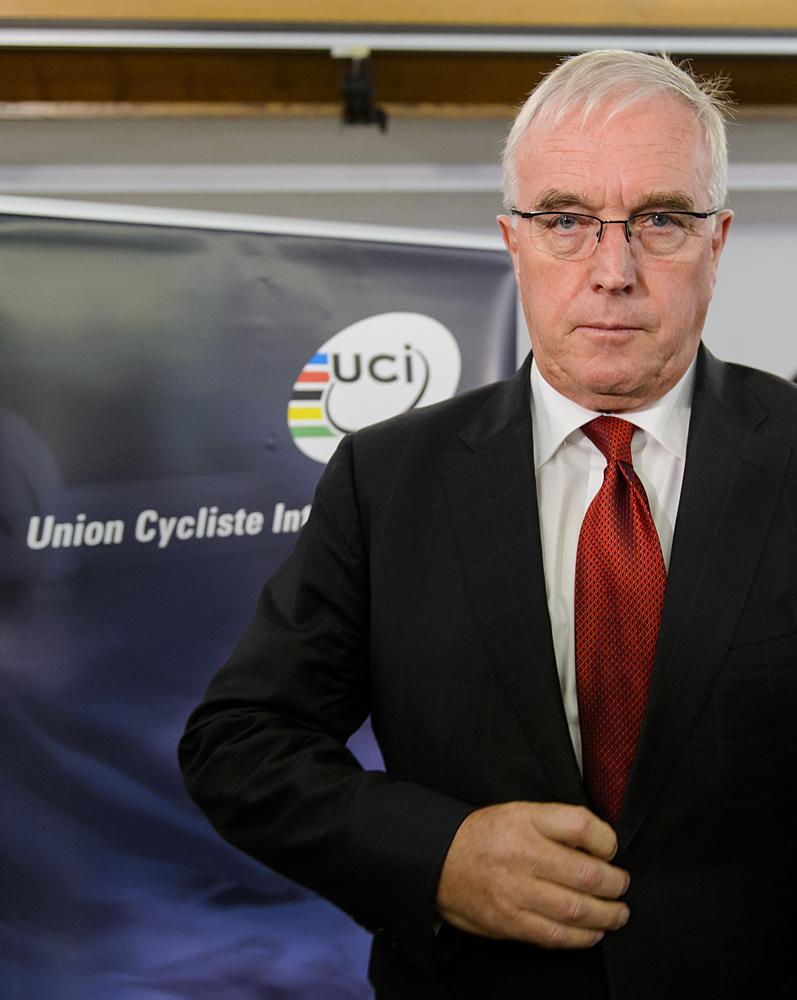

This strategy was driven by then UCI President Hein Verbruggen and to a later extent by his replacement Pat McQuaid, with assistance by former Medial Commission chief Lon (Leon) Schattenberg and the UCI’s external lawyer Philippe Verbiest. Verbruggen was described by UCI staff as the "patron absolu" during his presidency, while Schattenberg, Verbiest and Verbruggen were dubbed the "Flemish or Dutch Connection" by interviewees because they held secret meeting to discuss and decide important anti-doping matters.

The CIRC report divides the last 23 years into several periods, recalling the belated introduction of 50% blood haematocrit health checks in 1997 to try to stem the massive abuse of EPO, the return of blood transfusion in races after the introduction of a urine test for EPO, the creation of the Athletes Biological Passport (ABP) in 2008, and the creation of the independent Cycling Anti-Doping Foundation. The UCI is praised for being at the forefront of the fight against doping compared to other sports but the CIRC report also highlights how riders, teams and their doctors worked their way around every anti-doping procedure, often with help from complicit UCI personnel.

"Going after the cheaters was perceived as a witch-hunt that would be detrimental to the image of cycling," the report claims.

From a ‘period of containment’ to the Biological Passport

The CIRC describes 1992-2006/2007 as a "period of containment", with Schattenberg's approach described as "old school." He was against out of competition testing and documents show that he "advised the teams of newly implemented detection methods" including even the detection window for EPO, so that riders could know when to stop taking the blood boosting drug.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

While EPO was rampant in professional cycling, the UCI's anti-doping unit was tiny, with only three members of staff in 2003 and only five in 2007.

Yet the CIRC suggests that the UCI knew about the huge problems EPO was creating. The UCI held a meeting with laboratory testing labs in 1995 but only acted in 1996 when "the misuse of EPO had spiraled out of control and that there was a serious and acute danger that riders would die on the Grand Tours."

It was the various team doctors and managers who went to the UCI and begged them to start blood controls, with the 50% haematocrit rule and 15-day 'rest' period introduced. However teams quickly discovered ways of getting around the tests by manipulating their blood values, with some teams quietly advised to lower the athletes’ haematocrit levels by the UCI. Mario Zorzoli joined the UCI at this time to run the programme and would go on to become the UCI’s official Doctor but he continued Schattenberg’s rider-friendly approach to fighting doping.

According to an anti-doping expert who spoke to CIRC, "over 90% of the riders had a natural haematocrit level of around 42-43% and, thus, had a strong incentive to raise their levels closer to 50% and achieve considerable performance-enhancing effects without breaking the no-start rule." By the time the Festina Affair exploded at the 1998 Tour de France, riders widely believed that anyone who used EPO was not "cheating", but rather "applying the moral standards of the cycling community."

Riders were also warned if their blood and urine tests were considered suspicious, with the CIRC report confirming that Lance Armstrong’s former teammates Kevin Livingstone and Tyler Hamilton were just two of the riders who were given a friendly warning by the UCI that they were being scrutinised instead of being target tested more intensively.

During Lance Armstrong's dominance at the Tour de France, the UCI introduced out of competition testing but the programme was hampered by a lack of information on rider whereabouts until 2008. Between 2001 and 2005, only 2.5% of tests were out of competition tests, making easy for riders to dope during training and 'prepare' for major race with little risk of being caught.

CIRC reports that 53% of the anti-doping budget is spent on its out of completion testing programme, with "nearly half of all the urine samples taken (93% of those for OoTC) now tested for EPO."

McQuaid involved in anti-doping affairs

A turning point in UCI’s Anti-Doping Program came when Anne Gripper took over the Anti-Doping Unit in 2006. The UCI was under intense pressure after the explosion of Operación Puerto and Floyd Landis’ positive test at the Tour de France. Schattenberg finally left the UCI in 2007 but refused to speak to CIRC. Brian Cookson moved quickly to terminate Verbiest’s longstanding and lucrative legal advisory role to the UCI when he became UCI president in 2013.

Arguably one of Pat McQuaid’s best decisions during his time as UCI President was to appoint Anne Gripper as the head of the Anti-Doping Unit in 2006 but he also wanted to be involved in anti-doping affairs despite cultivating a close relationship with Lance Armstrong and being at the beck and call of Hein Verbruggen, who helped to secure his election.

The CIRC report says McQuaid "would advise the ADU staff to test certain riders at a certain time or to test them more frequently, to notify an athlete personally of an anti-doping rule violation (ADRV), decide to shorten the waiting period for a comeback to competition of a cyclist."

The Cycling Anti-doping Foundation (CADF) was created in 2008 to facilitate financial contributions to the ever-more expensive fight against doping with teams and race organisers obliged to cover much of the costs. Anne Gripper suddenly quit her role in 2010 and was replaced by Francesca Rossi but the CIRC report does not clarify why. However during a re-organisation and a push to secure ISO-accreditation, "a considerable number of the CADF staff was replaced".

Under new rules in 2013, the UCI President is no longer the chairman of the CADF and the new board members do not hold positions within the UCI.

The next step in the fight against doping

CIRC considers the introduction of the Athlete’s Biological Passport (ABP) in 2008 as a "'leap forward', with "Athletes, NADOs and laboratories have told the CIRC that only little advantage can be gained by applying refined doping techniques that stay under the ABP radar."

However it also admits that after several years and several high profile cases Biological Passport cases, "It is widely acknowledged that the “normalisation” of the riders’ profiles is the consequence of a different doping strategy that enables the riders to stay below the ABP-radar."

The Biological Passport has clearly helped stem the use of doping and reduced its benefits, but the CIRC report highlights that there is currently nothing anti-doping experts can do further improve the Biological Passport system.

It suggests that better intelligence, including criminal information, could help the fight against doping, by further improving target and out of competition testing. In January 2015 the UCI apparently hired an analyst/intelligence coordinator with a criminological professional background in order to help devise and implement intelligent testing strategies.

In its recommendations, the CIRC report also called on the UCI to focus on a qualitative approach to sample testing, selecting anti-doping laboratories for their best performance level in detecting banned substances rather than opting for the cheapest available.

While the 2015 WADA anti-doping code helps the UCI to investigate doctors and team personal who have helped riders to dope, the CIRC report called on the UCI to do so retroactively within the statute of limitations.

Stephen is one of the most experienced member of the Cyclingnews team, having reported on professional cycling since 1994. He has been Head of News at Cyclingnews since 2022, before which he held the position of European editor since 2012 and previously worked for Reuters, Shift Active Media, and CyclingWeekly, among other publications.