CIRC: No new doping admissions or proof of corruption in UCI

228-page report shows breaches of rules but CIRC stops short of corruption charges

The UCI has published the findings of the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC), with no new admissions of doping or proof that the UCI under Pat McQuaid facilitated or covered up doping. The 228-page report gives a lengthy history of doping within the sport of cycling, details of current suspected doping methods and recommendations for the future.

CIRC recommends retroactive testing, survey of doping

CIRC: Lance Armstrong's ban holds as McQuaid and Verbruggen fall under scrutiny

CIRC finds no proof of UCI corruption but questions linger over governance

CIRC suggests that doping has gone underground with micro-dosing and TUE abuse

CIRC uncovers serious weaknesses in UCI anti-doping strategy

The report is based on the findings of Dr. Dick Marty, a former Swiss State Prosecutor, Ulrich Haas, an expert in anti-doping laws, and Peter Nicholson, a former military officer who specializes in criminal investigations. The Commission conducted a 13-month investigation, which was funded by the UCI, that undertook 174 interviews from UCI personnel, teams, federations, doctors, riders and former riders, sponsors, event organizers and journalists.

No riders came forward to voluntarily admit an anti-doping rule violation (ADRV), and only sanctioned riders volunteered to provide the CIRC with information in order to try and have their sanctions reduced (p. 18). In addition, people asked to cooperate with the investigation were under no obligation to participate in the process and several people including riders, scientists, ex-riders or former UCI staff members refused to be interviewed by the CIRC (p.19).

“I would like to thank Dick Marty, Ulrich Haas, Peter Nicholson and CIRC’s staff for all their extensive work in producing such a comprehensive and rigorous investigation," UCI president Brian Cookson said in a statement. "Very few, if any sports, have opened themselves up to this level of independent scrutiny and while the CIRC report on the past is hard to read for those of us who love our sport, I do believe that cycling will emerge better and stronger from it.

"I made a promise before I was elected that I would ensure as a priority that under my presidency a respected and fully independent commission would investigate the UCI’s past and I am pleased to have delivered on that promise, on time and on budget. We gave the CIRC access to all our files, a complete copy of all the electronic data which existed when I was elected and full co-operation from all our staff. I said from the outset that the UCI would publish the CIRC’s report and recommendations to ensure transparency and that is exactly what we have done today."

The CIRC report was broken down into three chapters; Elite Road Cycling, Union Cycliste Internationale and Recommendations.

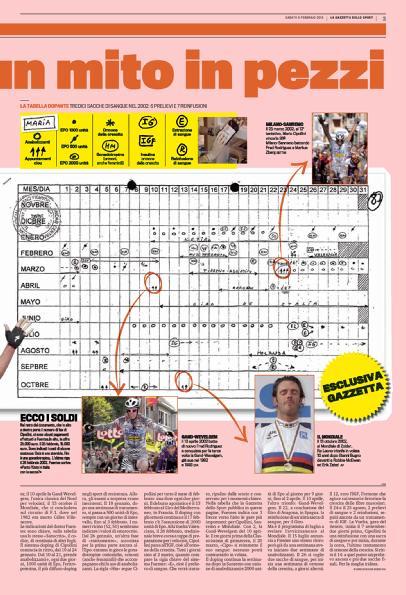

Doping in elite road cycling - timeline

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

• EPO was a revolution in doping in cycling, beginning in the late 1980s

• Introduction of the EPO test led to micro-dosing and more blood transfusions

• Riders adapted to new tests by changing their doping practices

• Smaller gains in performance are allowing riders to see that it is possible to win races and have a career in cycling with out cheating

• 90 per cent of TUEs were used for performance-enhancing reason

• The prevalence of doping in cycling today is unknown

The role of the UCI

• Growth of EPO use was faster than UCI was equipped to handle

• Conflicts between Verbruggen and Pound, UCI and ASO/AFLD reflected poorly on UCI

• Independence of the CADF a key factor in restoring the UCI’s damaged credibility

• UCI warned teams of new testing techniques and detection windows

• Effectiveness of the Athlete Biological Passport - pros and cons

• General concerns with the anti-doping system

Allegations of corruption and conclusions

The CIRC was also tasked with investigating allegations of corruption, breaches of the UCI Anti-doping Rules and preferential treatment toward Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador. The CIRC’s conclusions surrounding each allegation are as follows (A 2.4, p. 160-198):

Allegation: The UCI covered up a positive test of Lance Armstrong from the 2001 Tour de Suisse.

Conclusion: The CIRC concluded that Lance Armstrong did not technically test positive for EPO or any other doping substance during the 2001 Tour de Suisse. The sample was deemed suspicious but did not constitute an ADRV.

Allegation: Lance Armstrong financed the Vrijman Report and limited its scope

Conclusion: The CIRC did not find any evidence to corroborate the allegations that Lance Armstrong helped to finance the Vrijman Report, other than coincidental timing between it and Armstrong's donation of $100,000 to the UCI for anti-doping equipment. But it did find that the UCI allowed Armstrong's team to limit the scope of the report, letting them add to and redact parts of Vrijman's supposedly independent report.

Allegation: Allegations of corruption in the “Report on Corruption in the Leadership at the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI)”

Conclusion: The full report is confidential, however, based on the public version entitled the Makarov Report, the CIRC recommended that the UCI Ethics Commission or an independent body with investigative powers set up by the UCI investigate the leads identified in the report.

Allegation: Breaches of the UCI Anti-Doping Rules of three test between 1996 and 1999

Conclusion: The CIRC did not find information on positive tests for the three riders in question, because the national federations were in charge of anti-doping at the time, and so it cannot confirm or refute the allegations.

Allegation: 1997 Laurent Brochard case (lidocaine) and 1999 Lance Armstrong case (corticosteroids) back-dated TUE

Conclusion: The CIRC found that the UCI failed to apply its own rules (Article 43) in the Laurent Brochard and Lance Armstrong cases which constituted a serious breach of its obligations as the international governing body for cycling to govern the sport correctly.

Allegation: Preferential treatment of Lance Armstrong by the UCI leadership

Conclusion: The CIRC cited numerous examples that prove that Lance Armstrong benefited from a preferential status afforded by the UCI leadership. It states that the favours were granted to him because he was considered the greatest cyclist and a public hero as a cancer survivor.

Allegation: Allegations regarding UCI’s favourable treatment of Alberto Contador

Conclusion: The CIRC stated that it is of the opinion that the same rules and procedures should have applied to Alberto Contador as to all riders irrespective of his ranking and status.

Recommendations made by the CIRC

The CIRC ended its report with a series of additional recommendations in the following categories: legislative framework, operational, governance and changes to the sport (A3, p.211-228).

Legislative framework:

• UCI work more closely with governments and national authorities, which have better investigative powers

• Governments to provide better legal framework to sport organizations

• Doctors who are guilty of anti-doping rule violations should be investigated

• Amendments should be made to the WADA Code to provide for commissions as a tool to investigate doping scandals or monitoring compliance with the WADA Code

• UCI to use its full discretion in the context of financial sanctions

Operational:

• More studies of the prevalence of doping in other countries, teams and levels

• CADF to move to a qualitative testing rather than quantitative testing plan

• UCI and CADF should be more unpredictable when testing, to include testing from 11pm-6am under certain circumstance and improvements to the ADAMS notifications, re-testing, quality-drive doping controls from officers that are professional and well trained

• The UCI should set up an independent whistleblower desk

• The CADF put more of a focus on non-analytical investigations

• Laboratory need to impose confidentiality rules to its personnel involved in the results management process

• Improvements to the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP)

• Allocating funds to medical, scientific and technical research

• Anti-doping entities need to develop closer connections with the pharmaceutical industry

Governance:

• UCI to carry out a study on the election process to make it more transparent, democratic and straightforward

• Better financial control and accountability for the UCI

• Revamping the Ethics Commission

• Management Committee should be more active ad accountable

• UCI should facilitate the creation of a strong riders’ union

• Using sanctioned riders as educational tools

Changes to the sport:

• Investigate individuals suspected of doping in the past

• Paying more attention to medical conditions to better understand how and when to grant TUEs

• Study the feasibility of a centralized pharmacy at races for the peloton

• All teams and riders should be subject to the same testing and at a high standard

• UCI to address the lack of financial stability for teams and riders

Summary of the CIRC's findings

Chapter 1 provided an introduction to elite road cycling and the prevalence of doping in the sport today. The CIRC believes that even though doping and cheating in cycling is still evident today, it is not as endemic as it used to be, and the sport is on an upward trajectory (A1.1, p.20).

In Article 1.3, the Commission begins the historical timeline of doping in elite road cycling from the 1890s-1980s where cyclists used stimulants such as alcohol, caffeine, heroin and cocaine to alleviate fatigue, citing athletes such as the late Knud Jensen and Tom Simpson, and Jacques Anquetil’s use of stimulants. It goes into Hour Record cyclist Francesco Moser’s relationships with doctors Francesco Conconi and Michele Ferrari, and his use of erythropoietin (EPO) in 1984 and blood transfusions in 1999 (A1.3, p.31). The section also provides an overview of the history of anti-doping regulation because doping in the late 1980s went from being unsophisticated to frequent and organized.

The 1980s-2001 is titled as the EPO era and states that the blood booster was a revolution in doping in cycling and that although it emerged in the late 1980s, its use became more prevalent in the 1990s, and interviewees noted performance gains between 10 and 15 per cent. Drugs that also became popular during this time were anabolic steroids and human growth hormone (HGH). EPO was included in the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) list of banned substances in 1990, however there was not test to detect the drug at that time.

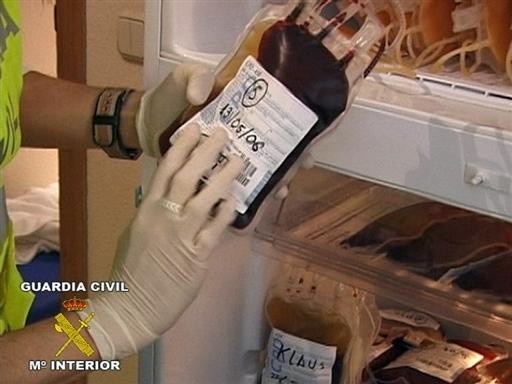

However, the report explains how the peloton adapted to the evolution of the EPO test by shifting to blood transfusions and EPO micro-dosing from 2001-2007.

The first test for homologous blood doping was used at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. During this time period doping scandals emerged with the Tyler Hamilton and Santi Perez cases, both of whom tested positive for homologous blood doping (A1.3, p. 44).

Along with blood doping, this section also points to the correlation between the introduction of the EPO test, and the athletes’ shift from subcutaneous to intravenous injections, and micro-dosing in order to avoid detection. A former rider stated that by micro-dosing and administering EPO intravenously, the detection window for EPO was significantly shortened.

In Article 1.4, the Commission suggests that the introduction of the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) by the UCI in 2008 transformed the doping landscape, and has made doping much harder for riders.

Current state of doping

The Commission notes that given the doping timeline, it was clear that riders have adapted to new anti-doping tests by changing their practices. The report suggested that it is difficult to know how many cyclists are using performance enhancing drugs today because they have been forced to dope “underground”. One interviewee felt that 90 per cent of the peloton was doping, however, another interviewee felt that it was around 20 per cent (A1.4, p. 56). The CIRC report notes that the shift to micro-dosing has led to a drop in performance gains from 10-15 per cent to 3-5 per cent. These smaller gains in performance are allowing riders to see that it is possible to win races and have a career in cycling with out cheating, in effect changing the mentality about doping (A1.4, p.56).

However, the report also discusses various types of performance enhancing substances and prohibited methods that riders undertake in order to avoid detection in the ABP. For example, one rider’s doctor instructed blood transfusions of a maximum of 150-200 ml, instead of 500ml bags that were previously used by the USPS/Discovery Channel and Telekom/T-Mobile. In addition, riders felt that they could get away with micro-dosing using EPO if they took the substance in the evening because it would be out of their system by the time anti-doping controls officers arrived at 6am to test (A1.4, p. 58).

Riders also continue to use ozone therapy, steroids, testosterone patches and HGH and GW 1516, among others, today. In addition, riders have abused the Theraputic Use Exemption (TUE) by requesting them for corticoids, which they were mainly used to reduce pain and achieve weight loss. The long list of substances used that are on the banned list can be found in A1.4, p. 63. However, riders also use substances that are not on the banned list such as painkillers and Viagra.

Sources of these substances were from false prescriptions, pharmacies, hospitals, through other riders and team staff, the internet, gyms, anti-aging clinics (A1.4, p.64).

One interviewee believed that 90 per cent of TUEs were used for performance-enhancing reason. Members of the Mouvement Pour un Cyclisme Crédible (MPCC) have decided that TUE applications for intra-articular corticoid injections should be accompanied by an automatic eight-day rest period (A1.4, p. 62).

Corruption within the UCI?

Part of the CIRC’s investigation involved finding out whether or not UCI officials contributed to the culture of doping and to investigate allegations of corruption, breaches of the Anti-doping Rules, and that it gave preferential treatment to Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador.

The CIRC begins by giving an overview of some of the issues that may have led to the UCI being seen in a negative light over the years. It acknowledges the complex nature of the sport of cycling as compared to other sports, and a history of the rapid growth of the UCI. It also touched on the conflict between Hein Verbruggen (President of the UCI from 1991-2005) and Richard Pound (President of the WADA from 1999-2007) and how their personal conflicts reflected poorly on the UCI from the public’s perspective.

In addition, the conflicts between the UCI and the Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO) and the French Anti-Doping Agency (AFLD) also brought negative attention to the sport governing body (A2.1, p. 93). The report also suggests that UCI was not equipped to handle the growth of EPO use in cycling because it was still at a developmental stage and didn’t have the human or financial resources to combat the problem (A2.1, p. 95). It cites the UCI as having had an ineffective governance and a poor communication strategy at that time.

The CIRC found that the UCI leadership took unilateral decisions without consulting the Management Committee in its previous administrations, and revealed that the "Dutch connection" - former president Hein Verbruggen, attorney Philppe Verbiest and Lon Schattenberg, head of the anti-doping unit - held secret meetings, and the autocratic leadership style continued with Pat McQuaid, they did not uncover concrete evidence of corruption.

The report labels McQuaid as a "weak leader", who never separated himself from Verbruggen, and was critical of the president's close relationship with Lance Armstrong as an obvious conflict of interest.

Current president Cookson lauded the report, and touted the changes his administration has made since he took office in 2013.

“It is clear from reading this report that in the past the UCI suffered severely from a lack of good governance with individuals taking crucial decisions alone, many of which undermined anti-doping efforts; put itself in an extraordinary position of proximity to certain riders; and wasted a lot of its time and resources in open conflict with organisations such as the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA)," Cookson said. "It is also clear that the UCI leadership interfered in operational decisions on anti-doping matters and these factors, as well as many more covered in the report, served to erode confidence in the UCI and the sport."

“I am absolutely determined to use the CIRC’s report to ensure that cycling continues the process of fully regaining the trust of fans, broadcasters and all the riders that compete clean. I committed to this process before I was elected President and I'm pleased to see the CIRC complete its work. I shall be giving some more detail on how we will implement recommendations from the report during the course of this week."

Cyclingnews will be publishing more detailed analyses of each section over the course of the next few days.

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.