WorldTour Week: Back from the brink

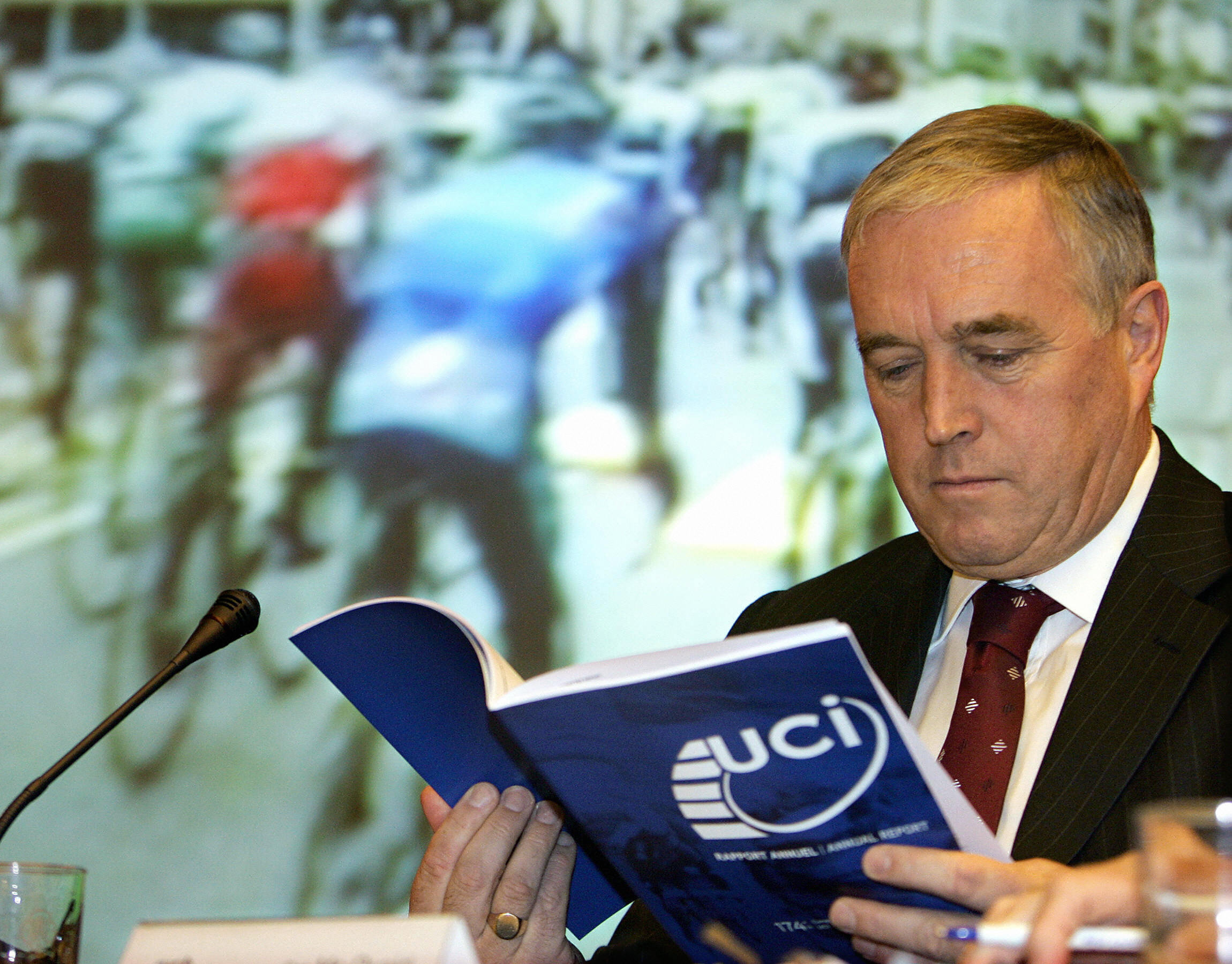

Former UCI president Pat McQuaid and how the WorldTour was almost lost

This week, Cyclingnews takes a deep dive into the UCI WorldTour and the global reforms of professional cycling first introduced in 2005, and the impact it has had on the sport. First, we looked at the history of cycling's other series. In part 2, we recapped the formation of the WorldTour and its challenges. Later this week, we will examine the impact the global reforms of the sport have had on teams and riders, and the globalisation of the sport of cycling. Today, we discuss with former UCI president Pat McQuaid the battles they faced with race organisers, in particular the Tour de France owners ASO.

Cycling is one of the oldest professional sports but throughout its history it has struggled to develop as successfully as other sports, in large part because of the relative strength of major race owners like the ASO, which organises or has a large stake in more than half of race days on the current WorldTour calendar.

The power struggle between teams, organisers and the UCI has kept cycling locked in the sponsor economic model and so lagging behind other sports and entertainment sectors in terms of economics and professionalism. A businessman by trade, Hein Verbruggen recognized the fundamental problems of cycling and came up with the concept of the ProTour to address its economic instability.

"Make no mistake about it - it was a vision of Hein Verbruggen," McQuaid tells Cyclingnews from his home in Provence, France, where he now operates a cycling holiday business.

"He was the one who came up with the vision, and he had been presiding over pro cycling for 12 years by then. He had seen all the lack of stability, he'd seen all the negatives in relation to pro cycling, and he wanted to try to put it on a more professional and stable platform."

Verbruggen, a former sales manager with candy-maker Mars - at the time one of the sport's biggest supporters - understood what sponsors needed to engage with the sport. According to McQuaid, that knowledge helped him conceive the idea of the ProTour, which was then developed through discussions with the UCI's board and other stakeholders.

"The UCI and Verbruggen worked closely with the major stakeholders ASO, RCS Sport and Unipublic, to try to get them around to the idea of this calendar and these obligations that were going to be put into it. They had many discussions and many meetings on it in 2003, 2004," McQuaid recalled.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The ProTour was meant to solve the issue of race organisers being able to pick and choose which teams they invited to their events. Team sponsors expected to see their riders in the biggest races, but one misstep, failure to 'activate' sponsorship with the race, a doping infraction or just the wrong nationality could see a team get passed over and end up losing their sponsorship.

"It was a huge amount of instability - for the teams and the sponsors," McQuaid says.

"The sponsors came in and got a couple of good years in terms of the payoff for their sponsorship, but generally speaking, because there were no guarantees they would be in the Tour de France, or the Giro d'Italia or the major Classics. Without those guarantees, sponsors wouldn't stay around too long.

"Another part of the ProTour was the administration of the teams. When Hein Verbruggen moved into cycling first in the 1970s-80s, he realized the sport was made up of black money - about 80 percent of salaries were black money."

The 'black money' in question involved falsifying contracts to avoid income taxes, putting a lower figure on paper and being paid the rest under the table, tax-free.

"[Verbruggen] dealt with that early on in his tenure as president, getting the teams with proper contracts and trying to introduce minimum salaries - but there was still a fair bit of black money."

These changes came with resistance from the teams, who also realized that being obliged to field teams in more races meant they would need to hire more riders, have more buses and team cars, staff and directors - it would all mean more money from sponsors.

"The teams looked at it, and a lot of them said it's too much for us - we're going to have to have 25-30 riders to race all these races you're asking us to do. There was resistance from them in that sense. But once they got into it and realized that with the offers they have to sponsors, the sponsors can be found; they are out there with big money to commit to cycling if you have the platform to offer them."

The plan worked in that sense. Budgets went from a maximum of perhaps €5 million to an estimated €35 million for Team Sky this year.

"None of the main team directors now like [Quick-Step's Patrick] Lefevere or [Movistar's Eusebio] Unzue who have been there from the beginning would disagree that it hasn't made a huge change to their team incomes and rider incomes. Everybody has benefited. Rider salaries have gone up hugely," McQuaid said.

Negotiating with ASO

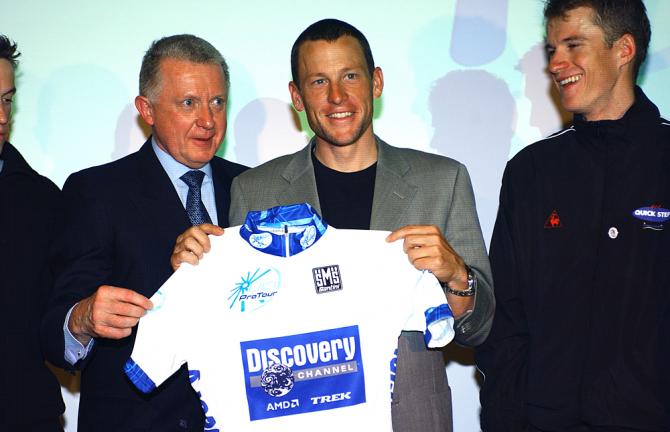

The benefits were not without great cost, however, as the UCI's efforts to reform cycling were met with fierce resistance from the race organisers, who would be required under the ProTour rules to invite all of the registered ProTour teams. Even before the gala which was to launch the series, the ASO, Giro d'Italia owners RCS Sport and the Vuelta a Espana's Unipublic conspired to bring the initiative to a halt.

"Hein Verbruggen spent a lot of time going from Switzerland to Paris and back, meeting with ASO in particular, with Jean-Marie Leblanc who was the top man at the time, trying to bring them along with the idea. They didn't want it - they wanted complete autonomy to invite whoever they wanted.

"They had initially agreed the actual makeup of the ProTour until a week or 10 days before the announcement. Then [ASO president] Patrice Clerc wrote Hein Verbruggen and said 'we're not going for it'."

The UCI had planned a gala to roll out the ProTour in Verona at the World Championships, but had to go back to the board which decided to use the reception to announce the new Continental circuits. They also decided to press on with the plans for the 2005 ProTour season in hope they could bring the ASO on board.

"We then went to war with them for three years," McQuaid says.

Verbruggen stepped aside after 14 years as president, and McQuaid was hand-selected to take his place, carrying on his vision of the ProTour. But the race organisers had dug in their heels, making demands to unravel key parts of the series and holding the teams as virtual hostages due to the importance of their events.

"We weren't operating on an agenda to try and damage organisers. Our objective was to improve the sport, because it's in competition with all the other major sports, and to improve the culture and tradition of the sport," McQuaid claims.

Throughout the opening four seasons of the ProTour, first Verbruggen and then McQuaid locked horns with ASO. At the time, only 20 or 21 teams were invited. With 20 licenced ProTour teams, it left ASO with limited ability to invite its home division 2 squads, among other issues. It came to a head in 2008, when ASO held Paris-Nice under the auspices of the French Federation (FFC), the teams were under threat of sanctions for violating UCI rules if they raced, but may have lost sponsors if they hadn't.

Behind the scenes, the race organisers had been plotting to create a competing "Grand Tour Trophy" - a series of 11 events, including the three Grand Tours, Milan-San Remo, Paris-Roubaix, Fleche Wallonne, Liege-Bastogne-Liege, Lombardy, and Paris-Tours plus Paris-Nice, and Tirreno-Adriatico.

But the UCI was not without leverage. It was the avenue through which national federations must pass to get to athletes into the Olympic Games in cycling. Much of their revenue depends upon the Games.

That summer, around the time of the Beijing Olympic Games, the UCI was planning to propose to evict the FFC from the governing body for not following the rules.

"We had the French Ministry of Sport - [Bernard] Laporte - he was against us, the ASO was against us. The French Olympic Committee was against us. All the French national administrators were against the UCI because ASO had told them that the UCI was threatening the future of the Tour de France. The Tour de France is a national treasure, it has historic value in French culture."

So it was at the behest of French president Nicolas Sarkozy that the two sides sat down in a meeting with the Tour de France bosses.

"He started a process which involved the Amaury family, Jean-Claude Killy, [IOC President] Jacques Rogge and the UCI," McQuaid says.

"We had a meeting in Jacques Rogge's office between myself, Verbruggen, the Amaury family and their main advisors. Rogge introduced the meeting, and he outlined how he saw the situation developing and the damage it was doing to the sport, etc. He said, 'now I'm heading out for the day, I'm leaving you with this office and my assistants, I would love to think that at the end of the day you might come to the basis of a solution'. That's what we did.

"There was quite a lot of misinformation being put out as well," McQuaid continues.

"The ASO, in particular, Patrice Clerc and Gilbert Ysern who were president and vice president of ASO at the time, had given misinformation to the Amaury family as to what the UCI's objectives were with the ProTour. When we explained how we saw it to the Amaury family, they didn't see that the threats were as great as what they thought they were.

The agreement took compromise on both sides. Clerc and Ysern left soon after, and the UCI agreed to make revisions to the rules from 2011 onwards. Importantly, they kept the number of teams to 18.

"From 2008 onward I had a very good relationship with ASO because an agreement was found between us, we stood behind our side of the agreement, they stood behind theirs, and we continued to work together," McQuaid said.

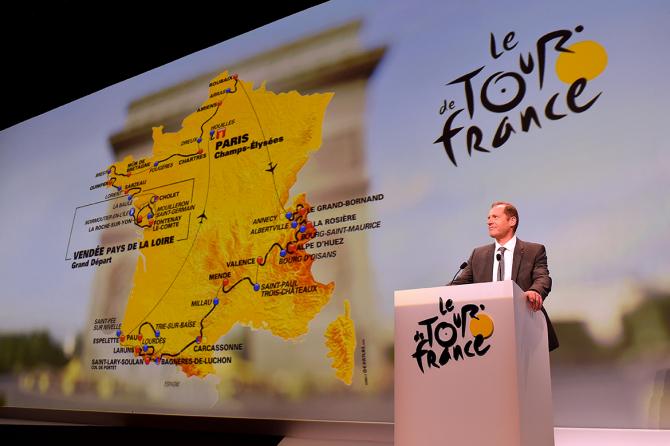

The ProTour becomes the WorldTour

There has been a lot of speculation as to what the UCI gets out of the WorldTour, which the series was dubbed after the 2008 compromises.

McQuaid dismissed accusations that the UCI was trying to pad its coffers or try to take broadcasting rights away from the race organisers, saying the work is purely to improve the sport.

"As president of the UCI your responsibility is all the different disciplines, obviously the road is the most important. You're trying to be objective and advocate for organisers, teams, and riders. With the ProTour and WorldTour, there were stated objectives and ways to get to those objectives, and it was all laid out in a well administered, professional way," he says.

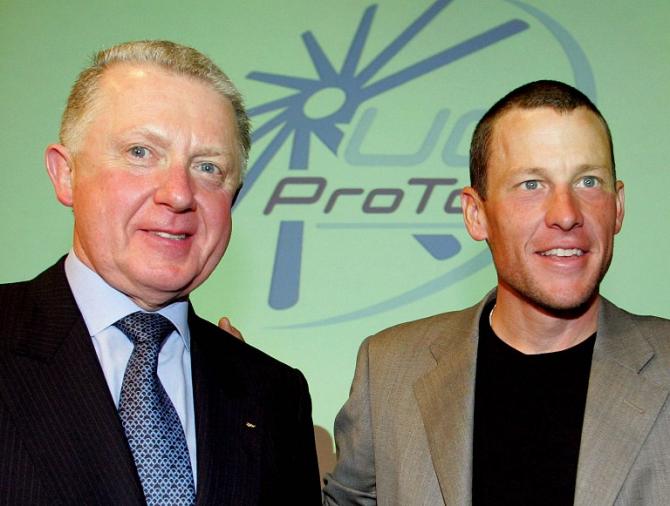

McQuaid lumps the notion of the UCI having a financial gain from the WorldTour with the allegations that he and his predecessor protected dopers like Lance Armstrong because of their value as stars in the peloton.

"Again, that's a lot of rubbish," he says. "The UCI's income - make no mistake - comes from the Olympic Games. The ProTour and Continental tours have nothing to do with it except for qualification purposes."

McQuaid insists that the costs of administration for the teams and races offsets any licence fees it collects.

"The WorldTour isn't certainly an earner for the UCI. And the other tours, the UCI actually spends money it gets from the Olympic Games [on them]."

He says the UCI did have an interest in improving the broadcast rights, but says they had offered the ASO an opportunity to bundle the rights for other events with their own.

"Anybody I've spoken to in the commercial world has told me that when you bundle, you succeed and you improve your situation. But ASO refuse to bundle, they want to sell their own events, even though the UCI offered them the opportunity to do the bundling on behalf of the sport, not on behalf of the UCI, but on behalf of all of the organisers of the events in the ProTour. They wanted to remain on their own, which they still do today.

"That was one objective of the ProTour you could safely say has failed, which I think is unfortunate, because it's still the best way to improve coverage of the sport.

"It would have had the ability to bundle all the rights of the WorldTour races together, you would have had a chance of both improving the income for all the other organisers and improve the overall income coming into the sport, and get more coverage because you have more to bargain with. That's not happening because ASO refused to do it, and that's still the case."

As he has in the past, McQuaid dismissed the notion that teams should share in the proceeds of selling TV rights, estimating that at most each team might get €1 million.

"What will they do with a million euro? They can pay more to riders to get on their team, that's all they'd do. That's not the commercial future for professional teams."

McQuaid's legacy?

In 2013, McQuaid was defeated by Brian Cookson for the UCI presidency, his legacy having been sullied by the doping saga of Lance Armstrong and accusations of corruption that dogged his re-election bid. Cookson won on a platform of transparency and stability, and took strides to reform the UCI's ethical charter.

But Cookson also was left with a WorldTour that was still in flux, and still under fire from the powerful cabal of race organisers, and undertook his own sweeping reforms. This year, 10 events were added to an already crowded WorldTour calendar, but the obligations for WorldTour teams to compete in them was removed under a revision of the rules rolled out this January.

The already confusing system became even more complex and undermined the whole concept of having the best riders at the biggest races.

"It's a complete mess now," McQuaid says. "There could have been one or two races added. It is a WorldTour, and any race that comes in should come because they're world-class races or they're in very strong strategic areas like China that are important for the sport. What was brought in was 10-12 races, mostly brought in for political purposes, the president of the national federation pushed for races in his area.

"In adding all of those races it showed me that there was no vision or strategy within the UCI to be doing that. I put that down to the president and the director general [then Martin Gibbs] who didn't have a proper strategy for professional cycling.

McQuaid agrees when asked if it hurts to see all of his hard work undone.

"It does, it hurts - there's no doubt. I spent three very hard years between 2005 and 2008 fighting for objective principles that I, as president, and the board of the UCI and the sport felt we wanted to get a system in place that was good for everybody.

"Those years took a fair bit out of me, there were some very dark nights during that time. We eventually succeeded - we didn't get 100 per cent what we wanted but we got 85 per cent - and I was happy we could develop that, fine tune it and bring it forward. It does hurt to see the complete mess that has been made of it."

The fall of Lance Armstrong via USADA's investigation and the numerous admissions from other riders that laid bare the scourge of EPO doping during Verbruggen's tenure and through McQuaid's time in office may have been his undoing, but McQuaid insists that the fight against doping would never have happened had it not been for the ProTour's creation.

With a series they could now sell to sponsors, the team owners now had something to protect, and the concept of the biological passport was born.

"It was through those discussions with people like Bob Stapleton and Henry van der Aat who was in charge of Rabobank at the time, who were business people and said 'we're going to have to really up the ante in anti-doping and show the world that we're doing more than anybody else'."

But the move to blood testing would prove far more costly than the cheaper but less effective urine tests. Had it not been for the team budget increases under the ProTour, McQuaid contends, that initiative could never have been launched.

"Our antidoping budget up to the time the ProTour started might have been €150-250k a year, then it crept up to 400-500k. Then it suddenly jumped to €4 million a year, which is what it is now. The UCI couldn't afford that."

The costs fell to the teams, with the WorldTour and Pro Continental licences now carrying requirements to pay into the Cycling Anti-Doping Foundation. Race organisers and riders also pay a part.

"It gave us a huge opportunity to do testing for the bio passport that I would maintain has worked, and has completely changed the peloton and their views, and arguably their actions over the last couple of years," McQuaid argues.

"It came about because of the fact that the teams were now operating on big budgets, and they realized that if we as a sport don't get to grips with the doping situation, the business of cycling is going to go completely. I think we've done that, and we dealt with it and the business of cycling still flourishes."

Laura Weislo has been with Cyclingnews since 2006 after making a switch from a career in science. As Managing Editor, she coordinates coverage for North American events and global news. As former elite-level road racer who dabbled in cyclo-cross and track, Laura has a passion for all three disciplines. When not working she likes to go camping and explore lesser traveled roads, paths and gravel tracks. Laura specialises in covering doping, anti-doping, UCI governance and performing data analysis.