WorldTour: 12 years under fire from ASO

A timeline of the battle from inception to today

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cycling has always suffered from its unique economic model - without the income of ticket sales or television rights falling to the teams, the sport is left to rely on the charity of the corporations it calls sponsors. The UCI has struggled throughout its history to improve the situation, but has been up against the titan of the sport - the Tour de France. The race owners Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO) remain the most powerful force in cycling, and rightly so since modern road cycling has its origins in the Tour de France.

The ASO (and its predecessor Société du Tour de France) has battled with the UCI for decades, most recently rejecting the approved WorldTour reforms and pulling their races from the calendar for 2017.

The origins of this modern war date back to the 1980s, when the UCI instituted the world rankings and later the World Cup, and used the points system to decide which teams could be invited to which races. Aside from shifting the internal dynamics of the team by placing pressure on more riders to get points, the rules began to dictate to race organisers which teams they could invite. This is a point which the ASO has never fully accepted.

The UCI wants to bring stability to the teams by offering multi-year licences, and therefore a guaranteed start in the major races, making it easier to sell the sponsors on the team and the media exposure the Grand Tours bring. The ASO are unwilling to give up control, and the phrase "we do not accept a closed system" has been their rally cry since day one.

2003 - the birth of reforms

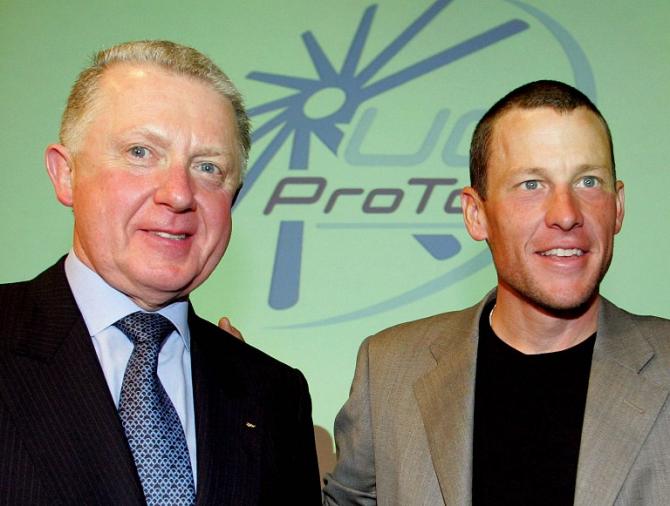

In 2003, the UCI began to draw up the scheme which would become the WorldTour. In June, 2003, then-UCI president Hein Verbruggen made the plans public, announcing a new European series aimed at attracting more sponsorship to the sport. Verbruggen envisioned a set calendar of 30-50 races, contested by 20-22 teams with the aim of boosting cycling's middle class.

"At the moment the sport depends on some 60 professional teams, some of which only have one sponsor," Verbruggen said. "There are less and less sponsors who can afford to invest in cycling, and they are reluctant to spend millions without knowing whether they will be allowed to enter the Tour de France."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Verbruggen's proposal included the "right and obligation" of all teams in the tour to race the events on this calendar, a philosophy which is still the cornerstone of the WorldTour today. By October, 2003, the Pro Cycling Council had approved the concept and the UCI got to work on making the newly dubbed ProTour happen. The new proposal was 20 teams for 30 events and 180 days of racing. It also included four-year licences, and ethical, financial and 'judicial' requirements.

Alain Rumpf, the architect of the ProTour espoused the benefits: "Teams and race organisers will be able to make longer contracts with sponsors. Just in recent months we've seen many contracts extended for three years or more. That's always been a threat to teams and to the sport. Sponsors often only confirmed for two years."

"We have concerns but not because of the Pro Tour itself, more about trends in the sport and trends that even go beyond cycling, like television air time. The Pro Tour is a response to that, an effort to make the top end of the sport more stable. We know there may be unforeseen consequences, with teams, sponsors, and so on. But there's huge support for the plan from different players."

Objections from organisers

Not everyone was convinced of the ProTour concept. Immediately race organisers began to complain - races that didn't make the ProTour might suffer. Races that did make the series would be required to invite 20 teams, and their choices of 'wild card' entries would be limited. Smaller teams which could not meet the financial requirements to join the ProTour began to fold. Teams opted out for fear their riders would be under pressure to race too many days. Finally, the Grand Tour organisers opposed inclusion in the ProTour, threatening the entire scheme.

In September, 2004, Christian Prudhomme stated his objections to a "closed system" in comments that exactly echo the concerns today. "The Pro Tour is a closed four year system with no possibility of up- or downgrading teams," he said. "If a team has a bad year, it still remains within the Pro Tour, but another team getting great results cannot move up into it."

By December, 2004, the ASO had come back to the negotiating table and quietly rejoined the ProTour. The decision was contingent upon teams agreeing to an ethical charter as the undercurrent of what we now know was rampant, organised doping, had hit its peak. The debate over the number of teams that should be in the WorldTour escalated during the season (a battle that would extend through 2008), and the ASO continued to express disdain for the licencing requirements. Then-ASO president Patrice Clerc stated, "We think it is inconceivable and unacceptable to ask for an organising license for our events; in a system that is just barely coming to life. Because these are the competitions that have created professional cycling in the first place!"

Clerc also railed against the idea of the UCI requiring it to share the television rights revenue, a concept which continues to be proposed today. "This point is about sharing (ProTour TV) rights as soon as 2008. In the past, it was referred to as something voluntary, but now, we find out that the final goal of the ProTour (is to make race organizers share TV rights), and this is also absolutely unthinkable to us. It would be like a joint venture. We do not want to enter a system of sharing (TV rights)," Clerc said.

As the racing continued, the polemics grew, culminating in Verbruggen having a diplomacy meltdown to the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf: "ASO will cooperate with nobody, but wants the ProTour to be organised according to its wishes. They want to dictate everything in cycling and completely work over the UCI. If we give any more, then we have nothing left. The UCI is a democratic institution, the legal power in the sport of cycling. So with this stance, we have made an end to the blackmail of ASO. I'm sick to death of the arrogance of the French."

In September 2005, Pat McQuaid took over as UCI president, but with Verbruggen staying on as Vice President, the battle continued unabated.

In December 2005, the Grand Tour organisers pulled out of the ProTour, putting their weight and €3 million behind a ‘Trophy of the Grand Tours', but the teams weren't buying it. In January, 2006, the AIGCP teams organisation came out in support of the ProTour. Meanwhile, the racing continued. Operación Puerto went down. At the end of the season, the ASO once again split with the UCI, insisting that the number of ProTour teams be reduced to 18 for 2007, then 16 for 2008, opening up more space for wild card invites.

The fight got ugly in 2007, with the ASO refusing to invite Unibet, the 19th ProTour team, for Paris-Nice. This violation of the rules led to a skirmish ahead of the race, with the ASO threatening to run the event under the French federation, and the UCI threatening teams with sanctions if they violated rules and participated in the race. The fellow Grand Tour organisers RCS Sport and Unibet followed suit with Unibet excluded from their events. Just five days before Paris-Nice, the UCI backed down and allowed the event to go ahead without Unibet.

The Grand Tour organisers won the battle in 2007, excluding Unibet from all three races despite the UCI's objections. Confident, the ASO, Giro d'Italia organisers RCS Sport and Vuelta a Espana's Unipublic carried the war into 2008, refusing to invite all ProTour teams. The ASO held both Paris-Nice and the Tour de France under the aegis of the French federation, and by the end of the season the UCI was proposing a new "World Calendar".

The new landscape

Over the past six years, the landscape of cycling has changed dramatically. Opposition to the UCI grew to such a pitch that some teams banded together to propose a 'breakaway league'.

The proposed World Series Cycling promised to be a "truly global" competition, with 14 teams and 10 new four-day events. It was backed by investors Rothschild and Gifted Group, but fizzled out under pressure from the UCI, amongst other factors.

By 2014, 11 of the WorldTour teams - Belkin (now LottoNl-Jumbo), BMC, Garmin-Sharp, Lampre-Merida, Lotto-Belisol, Omega Pharma-Quick-Step, Orica-GreenEdge, Giant-Shimano, Team Sky, Tinkoff-Saxo and Trek Factory Racing - came together to form the Velon working group conceived in 2013 on the heels of the breakaway league. Rather than create its own race series, the group instead seeks to give teams more of a voice in negotiations, and create new business models for the teams to pursue.

The teams continue to push for a bigger piece of the ASO's pie, with Velon seeking a portion of television revenue. The group put cameras on riders' bikes, and the ASO responded by teaming up with Dimension Data to put transponders on the bikes and offer live tracking by GPS.

At the same time, the UCI pushed through WorldTour reforms, which seek to increase the number of WorldTour races and extend the licences for both teams and races to three years, bringing back to the forefront the ASO's "closed system" argument.

With this latest move to step back from the WorldTour, the ASO uses the UCI's own rules against it. By sanctioning the races as HC, they gain full control over which teams to invite and weaken the WorldTour concept.

In turn, the move gives the ASO power to punish the Velon teams if it sees fit, so this announcement is not just a warning shot to the UCI, but to the teams and riders alike.