Why is Unbound Gravel mud so bad, how can racers cope, and can we predict where the worst sections will be in 2024?

Studying the geology and topography of Lyon County can provide helpful insight about where this year's mud pits will be

With Unbound Gravel 2024 fast approaching, the attention of all concerned is on whatever the most favorable weather forecast is. Last year’s edition of the biggest gravel race of the year was defined by mud. Sticky, claggy, and often unrideable mud sections that began from mile ten and served to clog up drivetrains and turn all tyres into slicks.

The forecast is, sadly, not hugely favorable at the moment. The route is heading north this year, which it has only done in 2019 and 2021, both of which were run in the dry. Kristi Mohn, marketing manager for the Life Time Grand Prix, says:

“The north mud is different than the south mud. It doesn't mean that there isn't mud, but it's just different. It doesn't stick as much. The north course does hold water a little bit better, but if it rains, you're riding on gravel roads, and that's just part of the deal.”

While this will undoubtedly be reassuring to riders, especially given the forecast, the end of that sounds somewhat resigned to the fact that if it rains there will be mud. Why, then, is the mud of Unbound so awful? The secret lies in the local geology.

Clay, not mud

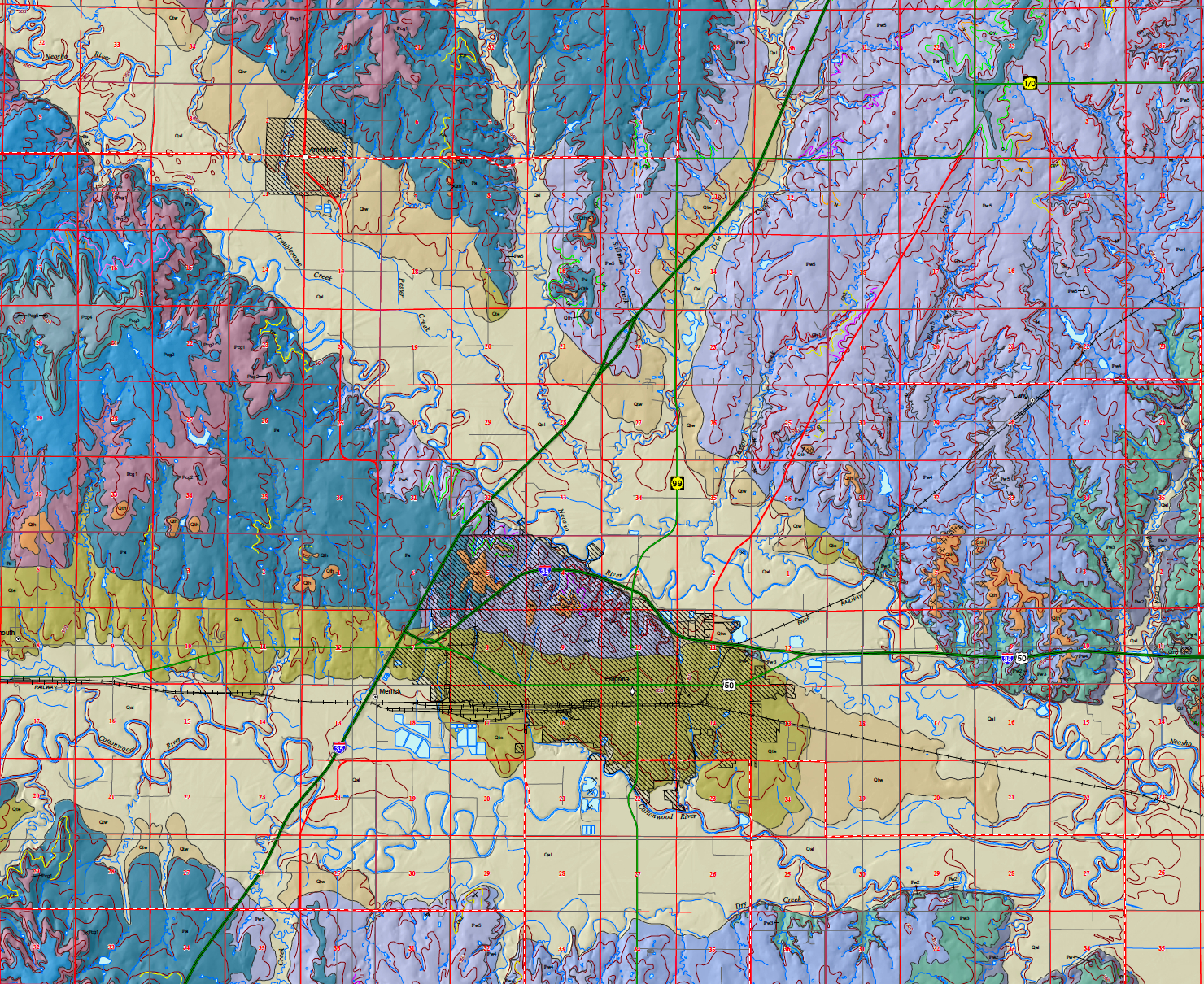

I’ll not bore you with too much technical information. I am, by training, a geologist, and even with an unnatural love of rocks the intricacies of sediments are soporific reading. The gist is that the local geology of the Unbound course, whether it’s the north or south route, is to quite a large degree comprised of clay-size particles, or actual clay minerals.

While you may think of clay as a colloquial term for that stuff that local artisans use to make expensive mugs to sell at farmer’s markets, it’s also a size; the finest size fraction of any sediment, below silt, and significantly finer than sand. A clay particle is anything below 0.002mm, which is essentially too tiny to fathom. The bedrock of Lyon County consists of a mixture of shales and limestone, both of which are themselves comprised of an unfathomable number of tiny clay particles.

When these rocks weather over millions of years, they break down into their constituent parts, and so the superficial deposits are incredibly clay rich.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Clay, as any local artisans who make expensive mugs for farmers markets will know, holds water incredibly well. An extreme way to think of this would be to think about pouring a glass of water into a fistfull of beach sand versus a very clay rich potting soil - one would drain very freely, one less so. To compound this, some clay minerals actually absorb water into their physical structure and swell in the process, meaning things take even longer to dry out.

As well as holding water and not drying out so much - meaning that if the course sees rain the day before it is likely to be claggy on race day still - it also adheres to itself. You can make a ball of clay (or an artisanal expensive mug), but try and do that with sand and you’ll end up with a pile of sand (or an extremely useless mug). It’s this inter-particle adhesion, aided and abetted by the surface tension of the water, that makes it so claggy. This is why it sticks to your bike, drivetrain, etc.

Sadly, if it was just clay it might be a little kinder on bike components, but the small quantity of coarser sand-sized particles made by erosion of the extremely resistant flint nodules, sit within the clay and make it act like a grinding paste.

The influence of rivers

This is going to sound like high school physical geography for a bit, but it is important, especially when it comes to predicting where the muddiest sections for 2024 will be. Clay particles are easily transported as they weigh very little. Low energy streams, and languid, slow, meandering rivers love clay. These rivers also concentrate deposits of clay, as anyone who’s been fishing on the edge of a muddy creek will know. As the river meanders about over millennia it picks up, sorts, and dumps thick deposits of clay.

To the south of Emporia lies the Cottonwood River, and the geological map shows lovely and clearly where it has meandered in the past. This is also roughly where the worst of the mud occurred, from what I can gather from an armchair perspective.

The north route doesn’t have to contend with the Cottonwood, but it does traverse the Neosho River, which is of roughly equal size and meandery-ness, as well as the forebodingly named ‘Troublesome Creek’ - As an aside, North American feature names like this are always a highlight.

Where will the mud be at Unbound this year?

Without driving the course myself I cannot be sure, but from a geologist’s point of view the north route doesn’t seem to have the same potential for disruptive mud as the south route.

The sections in the vicinity of the Neosho River deposits are done with by kilometer 7 when you’d start to climb, and being so close to the start, and with last year’s event in mind, I’d expect if these were really going to be disruptive the race organizers would simply route around them.

At around kilometer 110 there is a low point at Mill Creek, but this is a far smaller river, and the crossing of it is elevated meaning you never have to descend to the water level. There's every chance that crossing any of the innumerate creeks on the route may cause some mud issues, but they would hopefully be short lived and not leave riders resorting to protracted periods of hike-a-bike.

The real kicker may be right at the tail end of the race. At kilometer 300 or so, just after a small cemetery, riders will go back into the deposits of the Neosho. The route does skirt along the farthest northeast extent of these deposits though, and this, combined with the fact that these are more well used roads (as they are closer to Emporia) they give me less cause for concern. Again, I also suspect that after the negative press from the mud last year, if these became truly impassable the organizers would route around them, too.

Can I mud-proof my bike?

Not mud-proof, but there are a few things you could do to help your setup. Running skinnier tyres will allow more mud clearance between tyre and frame/forks, reducing the chance of them becoming totally gummed up.

Running tyres that clear well would also help - Either something with a relatively slick centre, or something with widely spaced knobs would do well. I have zero experience riding this terrain, but if I was to ride it I’d probably spec something like the Challenge Gravel Grinder.

The pros (and amateurs too) cary a paint stirrer stick to de-clog the bike should the worst happen. Praying for more rain might actually help, as it'll help things stay a bit more runny. Starting with a properly clean bike, and giving the frame a coat of polish (sorry, matte bike fans) will help stop mud sticking to it so easily. Be liberal with it, and if you’re in a pinch a rag and some GT85 will do a similar job. Just watch out near the brakes.

Will joined the Cyclingnews team as a reviews writer in 2022, having previously written for Cyclist, BikeRadar and Advntr. He’s tried his hand at most cycling disciplines, from the standard mix of road, gravel, and mountain bike, to the more unusual like bike polo and tracklocross. He’s made his own bike frames, covered tech news from the biggest races on the planet, and published countless premium galleries thanks to his excellent photographic eye. Also, given he doesn’t ever ride indoors he’s become a real expert on foul-weather riding gear. His collection of bikes is a real smorgasbord, with everything from vintage-style steel tourers through to superlight flat bar hill climb machines.