Where are they now? Team Sky's 2012 Tour de France-winning team

The key figures of the history-making British squad, over a decade on from their era-dawning victory

From their very earliest pronouncements, the raison d’être for Team Sky was clear: winning the Tour de France with a British rider.

Behind the scenes, the super-team had the much-trumpeted "marginal gains" philosophy: everything from leaders sleeping on the same memory foam mattress each night to Tim Kerrison’s forward-thinking sports science and altitude training camps on Mount Teide, overseen by team principal Dave Brailsford’s relentless drive and clear-eyed direction.

The richest team in the sport had the lofty budget to foot the bill for their progressive plans and recruit the best support riders. In the winter of 2011, they strengthened the team’s core with riders from the shuttering HTC-Highroad team, such as Michael Rogers, Bernhard Eisel and Mark Cavendish.

And, most importantly, they had the man for the job: Bradley Wiggins, a pursuit and time-trial star shaped into a consistent stage racer, experiencing a purple patch of form, confidence and success through 2012.

By the time July rolled around, the pressure was on: the team’s highfalutin approach left them to be shot at and they had struggled at the Tour de France in 2010 and 2011, learning lessons. It was all part of the build-up before it was third time lucky.

Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome finished first and second, with world champion Mark Cavendish winning three stages. Given the mixing and matching of objectives, the race wasn’t without internecine hiccups. Vincenzo Nibali (Liquigas-Cannondale) finished third, over six minutes in arrears.

"It got to the point where, in 2012, everybody knew they were riding for second place," sport director Sean Yates says. "They were beaten mentally straight out of the block."

In the mountains, helpers Michael Rogers and Richie Porte could ride to a certain wattage and pin back any attacks, with Edvald Boasson Hagen adding impressive versatility as a super-domestique. "Like Nico [Portal] told me a few times, when they had great results with a fantastic team, it was just like playing PlayStation," Yates says. "You had the manpower to dictate who did what, [and] when."

Sign up to the Musette - our subscriber-only newsletter

The triumph kickstarted the Team Sky era of stage racing dominance. For the next seven years, the squad were the reference point, even if their style of riding was far from universally popular. Detractors deemed their tactics, especially riding up key mountains in formation to a certain wattage, to be repetitive and robotic. It was certainly effective.

A happier, halcyon period came for the team and many of its members in 2012, years before the spectres of a jiffy bag and government select committee, a career-threatening crash for Egan Bernal and the emergence of a Slovenian youngster called Tadej Pogačar.

Only one rider in their line-up will still be a professional cyclist in 2025. So, what happened to Sir Bradley Wiggins and his eight teammates afterwards? What are they doing now and what are their memories of Team Sky’s epochal first Tour de France win?

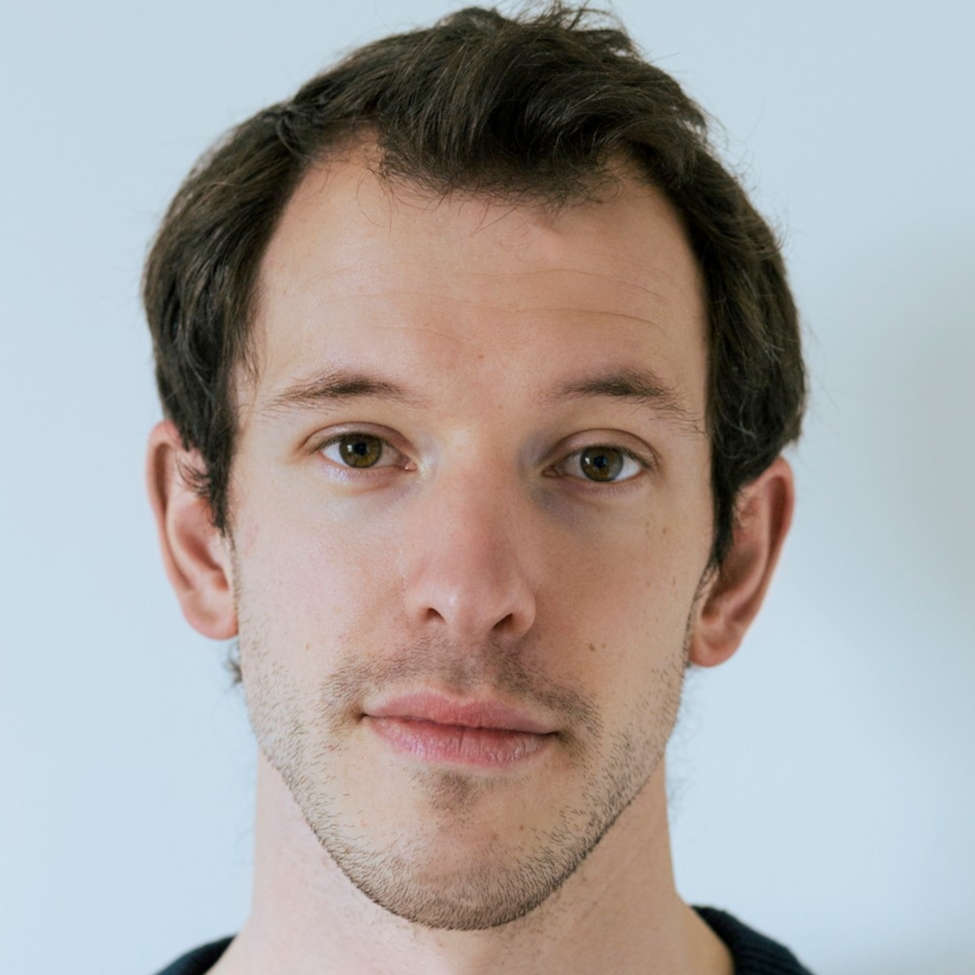

Bradley Wiggins

Wiggins was an all-or-nothing character. When on song, he lived like a monk off-the-bike and could beat anyone against the clock, so smooth on his time-trial bike that you could put a pint of beer on his back and he probably wouldn’t spill a drop. He could back it up with metronomic riding in the high mountains, before delivering bon mots to the press with chainring-sharp wit. But when off his game, his head wasn’t there, he would perform insipidly and flake out on engagements.

Since his breakthrough ride to fourth at the 2009 Tour de France, the sport’s flagship race became his white whale. Snagging it three years later sealed his annus mirabilis, in which he won Paris-Nice, the Tour de Romandie, Critérium du Dauphiné and both long Tour time-trials in Besancon and Chartres respectively.

Come the final weekend of that race, the Sun newspaper had cut-out sideburns on their front page and thousands of fans crossed the Channel to cheer on the first British winner. "Wiggo" was box office: the following week, he rang the opening bell of the London Olympics start ceremony before taking gold in the time trial.

Inevitably, the only way was down from that summit.

He didn’t race the Tour de France again as Chris Froome moved above him in the pecking order at Team Sky; signs of discord were clear in the 2012 race. The pair fell out, something Wiggins later said he regretted.

He has since reflected on the "intense, cut-throat" set-up at Sky, one which helped to make him but also partly broke him, driven by fear and pushed on by head coach Shane Sutton and principal Dave Brailsford. "It was like being in a cult," he told the High Performance Podcast recently.

Wiggins was knighted in late 2013 and became world individual time-trial champion the following year. He went on to break the Hour record and win Olympic team pursuit gold before retiring at the end of 2016.

He took up rowing in a brief bid to compete at the Tokyo Olympics and also had a spell as a pundit at GCN, with an eponymous podcast and occasionally reporting from a motorbike in-race at the sport’s biggest events.

However, the jiffy bag saga dented his reputation, with the revelation via a TUE leak that he had used the banned corticosteroid triamcinolone. Wiggins contended it was used medically for his asthma; a British government select committee report suggested it was to enhance his performance under the guise of treating that condition.

Wiggins has endured tumultuous years since stepping away from cycling. He separated from his long-time wife Cath in 2020 and went bankrupt, with recent reports suggesting he is £2 million in debt.

It has taken Wiggins many years to put together pieces of his dysfunctional past and understand their effect on him. He had idolised his bike racer father Gary, who walked out on the family as a baby and died in mysterious circumstances in 2008. He was sexually abused by a former cycling coach between the ages of 13 and 16. There was a self-destructive impact on his behaviour.

A canny impressionist who sometimes had his teammates in stitches, Wiggins found it hardest to be his true self. He adopted a cool persona or joked around to cope with the attention or conceal his intrinsic issues with self-worth. Cycling and the training process were his great distraction and confidence-giver.

His experiences underline the difficulty of both being a champion on the bike and life after it. There are stark differences between what we perceive on the outside and what’s really going on underneath.

Wiggins says that he doesn’t drink alcohol anymore, having used it as a crutch before. "I’m really on an upward journey now. I feel like I’ve come full circle from 2012," he said to the High Performance Podcast. "I finally took responsibility for my own life."

"The past has been the biggest thing that has helped reform me. What I have to do is not live in the past but change my relationship with it," he added.

The Wiggins name is still in the peloton. A dozen years since riding on the Champs-Elysées cobbles alongside his maillot jaune-clad father after his victory, his 19-year-old son Ben races for leading development team Hagens Berman Jayco in 2025.

Chris Froome

After his Vuelta transformation in 2011, Froome was visibly champing at the bit for an opportunity to lead.

He lost time due to a puncture on the opening stage. However, after winning his first Tour stage on La Planche des Belles Filles, there was the hiccup of an attack on stage 11 to La Toussuire, briefly dropping maillot jaune Wiggins.

Their partners later had a heated exchange on Twitter: "If you want loyalty, get a Froome-dog, a quality I value although being taken advantage of by others," Michelle Cound posted. You didn’t need to be Nostradamus to work out there was trouble ahead.

He became Team Sky’s frontman and cornerstone of their Grand Tour-winning dynasty. The Monaco-based rider was triumphant in the Tour de France in 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017, alongside the Vuelta a España in 2017 and the Giro d’Italia in 2018, the last time he won a pro race. His audacious 80km attack up and over the Colle delle Finestre to snatch the maglia rosa has gone down in cycling history.

Froome’s success ended with a career-threatening crash during a time-trial warm-up at the 2019 Critérium du Dauphiné. After drawn-out rehabilitation, he joined Israel-Premier Tech in 2021 but has been unable to replicate his old results. Team owner Sylvan Adams last year indicated that he "cannot be considered value for money."

Going into next season, the 39-year-old is the only member of the 2012 Sky Tour line-up still racing though he indicated recently that he expects 2025 will be his final season. He is still hanging out with old team-mates though: in a heartening Instagram bromance, Froome spent some of the winter with Mark Cavendish, racing in Singapore, doing a charity ride event in Miami and popping up in Taiwan alongside him.

Off the bike, Froome has a significant business portfolio. He is an investor for digital wallet Curve and, over the years, he has also invested in Factor Bikes, Supersapiens glucose monitors and Hammerhead cycling computers.

Michael Rogers

Rogers became a management assistant at Lidl-Trek in September 2024 across their men's, women's and development teams. Based in the Italian-speaking Ticino region of southern Switzerland, he’s more likely to be found pounding the pavement running than cycling.

He has taken a more entrepreneurial route since ending his career. While racing for Tinkoff-Saxo, Rogers was forced to retire at the start of 2016 after cardiac examinations showed occurrences of heart arrhythmia, as well as a congenital heart condition.

The man from New South Wales became the new CEO of VirtuGO, an online training platform aiming to be a Zwift rival. It closed in November 2019, due to user acquisition costs.

After a season-long stint at Team NTT as technical partner manager, he moved from the peloton to the corridors of power, joining the UCI and performing several roles, most notably Head of Road and Innovation, liaising with teams and organisers, and Head of Innovation and Esports.

At the 2012 Tour, Rogers was calling the shots as road captain and trying to take mental pressure off team captain Wiggins. "Bradley was one of my favourites to work with," he tells Cyclingnews. "He had this bubbly character. It was probably some of the best times I had in my career in this internal team environment. Maybe from the outside, it looks more serious, but internally we had a lot of fun," he says. Rogers would sometimes struggle to eat dinner because he was laughing so much.

"I was so inspired by Bradley, how hard he was training and the amount of time-trial work he was doing … great teams become great because they have a great leader."

Team Sky’s overall ambition in 2012 came at a cost for the era’s leading sprinter, Mark Cavendish. "There were days where Cav wanted to go for stage wins," Rogers says. "We had some really tough decisions we had to take on the road about who was going to be given priority."

Rogers does not have a 2012 yellow jersey at home as a keepsake, which he puts down to the hectic atmosphere, as Wiggins travelled to London post-race for the Olympic Games. "I don’t think we ever got the chance to really celebrate, it was all pretty serious until this big goal was done," Rogers recalls.

Edvald Boasson Hagen

The Norwegian was touted as the "next Eddy Merckx" in the early days of his career, winning 20 races with HTC-Highroad in 2008 and 2009.

Shunning the spotlight with his easygoing, quiet nature, it is easy to forget just how devastatingly strong and versatile he was. Focusing more on climbing at Team Sky after signing in 2010, Boasson Hagen was a bravura all-rounder, able to win harder bunch sprints, short time-trials and from escapes, despite some Achilles tendon problems.

His Tour de France stage victories – a brace in 2011 and another in 2017 – count as Boasson Hagen’s greatest racing memories, among over 80 triumphs in his long career. He was also second in the 2012 World Championship road race behind Philippe Gilbert.

Boasson Hagen retired at the end of 2024, finishing his career at Paris-Tours after spending his last season racing for French squad Decathlon A2GR La Mondiale. He intends to enjoy time at home in Oslo with his airline captain wife and their young child before finding a new job.

He now has the freedom to do more cross-country skiing, a discipline he regularly used for winter training. Recreational cycling events are also on the horizon: he will take part in the Leblanq Norway experience in May 2025 as lead rider.

The Norwegian could be using his hands as much as his legs in retirement. He is a keen photography buff and handy craftsman: during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, he welded together a barbecue set and furniture. One time, he even drew a table in the computer program SketchUp and made it in a neighbour’s workshop.

Richie Porte

Porte was a valuable right-hand man to Wiggins in 2012 and Chris Froome for his first two Tour wins. Time and time again, the Tasmanian was the last man in the mountains, setting a devilish pace that blew away rivals and their helpers.

Combining time-trial prowess with such climbing ability, he became one of the most successful week-long stage racers of his generation, winning two editions of Paris-Nice, a pair of Tours Down Under, the Tour de Suisse, Critérium du Dauphiné, Tour de Romandie and Volta a Catalunya.

Pursuing his own leadership opportunities, he left Sky for BMC Racing Team in 2016 and moved on to Trek-Segafredo, capping his career by finishing third in the 2020 Tour de France.

After retiring from pro cycling at the end of 2022, Porte moved to Launceston in his native Tasmania. He has been helping his builder brother as a labourer in the family trade.

The former triathlete swims regularly, doing as much as 10,000 metres in the pool some mornings. He still gets time in the saddle, supporting several charity rides. Retirement is "bliss … I like riding my bike, but I don’t miss the professional side of it," he told GCN in January.

In March 2024, he rode the 334km MAAP Equinox ride in the hills northeast of his home city with friend and fellow ex-pro Will Clarke. Some doing to make Milan-San Remo look like a short ride.

Nicknamed the "King of Willunga Hill" for his prowess on the Tour Down Under’s kingmaker, his Strava record of 6:34 from 2020 also still stands.

Mark Cavendish

It was a coup to have the Tour champion elect and sprint star on the same side, and Cavendish did not disappoint. Wearing the rainbow jersey of world champion, Cavendish won stage 3 to Tournai, adding stage 18 to Brive and the race finale in Paris.

But behind the scenes, it was not all happy families. With Team Sky regularly committing resources to protect their GC prospects rather than chasing breakaways, the team’s peerless sprinter felt like a "back-up rider." He realised the team’s quest for yellow superseded his personal desire to go for green and stage wins. The promise to go for both jerseys, on which he had joined the squad, was a false one.

Cavendish left for Omega Pharma-Quick Step in 2013 and continued his remarkable, prolific career. The rest is history: after overcoming Epstein-Barr and a late career blip, the Manxman bowed out at the Singapore Criterium in November, months after winning a 35th and final Tour de France stage to earn the all-time record outright.

Numbers don’t do justice to his longevity, tactical nous or lethal acceleration, and ability to kick again in his pomp. "The Manx Missile" has earned a more relaxing winter with his wife Peta and five kids at their home in Essex, not beholden to a training plan for the first time in over two decades.

How will he replace the routine and adrenaline rush of the sport? A close friend of ex-MotoGP competitor Cal Crutchlow, Cavendish has said in the past that he’d like to race motorbikes. He has also agreed to do the Paris Marathon with his brother.

But it’s likely he will stay involved in cycling in some capacity. "The past few years I’ve known what I want to do after. I’ve set the wheels in motion for that. I want to stay in management in the sport," he told Men’s Health in October.

Bernhard Eisel

The Austrian was one of the sport's most respected road captains, a team player who lived for the spring’s cobbled races.

A regular right-hand man to Mark Cavendish for much of his career, their paths deviated at Team Sky. After being part of the 2012 Tour-winning team, even setting the pace on some mountains, the former Gent-Wevelgem winner decided to stay put. Eisel’s four-year stint at Sky transformed his training. "They changed the sport and my approach to the whole sport," Eisel told Procycling in 2018.

That year, while racing for Dimension Data, Eisel crashed into a team car at Tirreno-Adriatico, suffering a subdural head haematoma and needing brain surgery, nearly ending his career prematurely.

After retiring at the beginning of 2020, he joined Eurosport and GCN as a presenter and on-the-ground pundit, which included doing what is seemingly a rite of passage for charismatic ex-pros, giving insight from the back of a motorbike mid-stage.

He has been a sports director at Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe since 2022. An Austrian on a team backed by an Austrian company seems an appropriate fit.

Christian Knees

The tall, low-key German spent ten years as a racer with Team Sky and its various incarnations. The 2012 Tour was his first involvement in a Grand Tour-winning team.

"His size was perfect for Bradley to sit behind … he could ride all day and hold a breakaway," sports director Sean Yates says.

A powerful unit on the flat with staying power on hills, he was also by Chris Froome’s side for his 2017 Tour and Vuelta wins, as well as his 2018 Giro triumph.

After retiring in the winter of 2020, Knees took his experience into the team car, becoming assistant sports director for INEOS Grenadiers. The former German road race champion has his own coaching company, PMP, and still rides regularly.

Kanstantsin Siutsou

Siutsou was the ninth and last name on Team Sky’s start list for the 2012 Tour; the UCI only reduced line-up sizes to eight riders for Grand Tours before 2018.

"Kosta" didn’t last long though, crashing out of the race on stage 3 to Boulogne-sur-Mer, fracturing the tibia bone in his leg. Accordingly, the likes of Porte, Knees and Rogers had to shoulder his workload.

A former under-23 world champion and stage winner in the 2009 Giro, he was a trusted domestique, completing 17 Grand Tours during a career predominantly spent with HTC-Columbia and Sky.

However, things ended ignominiously as the then-36-year-old tested positive for EPO in late 2018 while racing for Bahrain Merida and was banned for four years.

The Belarussian is now based in the Florida city of Sarasota. He is a co-founder and investor in Velotooler.com, a web-based program that connects retailers and cyclists with skilled bike mechanics.

According to his LinkedIn profile, for a couple of years between 2019 and 2021, he was also a tower climber, helping to build 5G telecommunication installations. Once you’ve cycled up 2,600-metre mountains and gone down them at warp speed, scaling a 100-metre tower probably holds no fear.

Dave Brailsford

The man who implemented a "marginal gains" philosophy to great effect at British Cycling and Team Sky has moved even higher up the sporting tree.

After first working with INEOS CEO and chairman Jim Ratcliffe when the company took over sponsorship from Sky in 2019, he was appointed Director of Sport at the INEOS group in late 2021. Brailsford collaborated with other leaders across their sports interests, including the New Zealand All Blacks rugby team, Ineos Britannia sailing team and French football club OGC Nice, with the aim of cross-pollinating new ideas.

It was a step back from hands-on management of the cycling team and, while it’s impossible to pinpoint the exact impact, results suffered. There were seven Grand Tour victories in nine seasons for Sky, but Ineos Grenadiers have not won one since Egan Bernal’s 2021 Giro title. Brailsford stopped being team principal of Ineos Grenadiers in January 2024, with John Allert coming in as chief executive.

Brailsford was a driving force, shaping the team’s philosophy with meticulous attention to detail, and pinning down a plan to go with the vision.

It was rarely plain sailing, mind. Their management figurehead came under fire in 2018 as a British parliamentary select committee accused Team Sky of "crossing an ethical line" with their use of therapeutic use exemptions (TUEs). In 2021, the team’s former doctor Richard Freeman was struck off the medical register after having a banned testosterone gel delivered to the National Cycling Centre in 2011. Brailsford denied wrongdoing and resisted calls for his resignation.

With Ineos buying 25% of Manchester United, he became an influential figure behind the scenes as Ratcliffe’s guru-in-chief at the club. Going from Ineos Grenadiers to the Red Devils is a step from the frying pan into the fire. Brailsford is no dyed-in-the-wool football expert, though he has now spent several years deep in the milieu.

Returning 13-time Premier League winners Manchester United to their former glories will be just as difficult as getting a Briton on the top step of the Tour podium.

In November, Portuguese manager Ruben Amorim came on board as the club’s new manager. So far, it seems to be more considerable pains than marginal gains: the iconic football club were languishing in 13th place in the Premier League at the time of writing, with fans up in arms about rising ticket prices.

Sean Yates

Yates lives in the little Spanish village of Useras, moving there after seeing the Valenciana area’s beauty on a rest day bike ride during the 2016 Vuelta while working as a Tinkoff-Saxo sports director.

Ever the maverick, Yates bought 30 acres of land five kilometres down a dirt track. For several years, he lived off-grid there in a caravan with solar panels, a vegetable plot, a compostable toilet and rainwater collection before moving to a house on the village outskirts.

The lead sports director for Sky back then regards the 2012 Tour as the zenith of his managerial career. "When you start with a new team, there’s kind of nothing to lose," he tells Cyclingnews. "Once you get to the top, you’re there to be shot at. But getting there is the fun bit."

"There were some conflicts. Ultimately, it was all about getting the job done," Yates says. "For me, the pinnacle was the Champs-Elysées. That will never happen again: a British yellow jersey holder leading out a British world champion to win the final stage of the Tour de France – with a British DS."

"Basically since Nico Portal sadly left us [dying in 2020], that was the start of the decline of Sky," Yates adds. "Dave [Brailsford] moved on, other people took over and it’s just gone downhill big time."

Yates last worked as a pro team directeur sportif with Italian squad Eolo-Kometa in 2022. He has a coaching business, Sean Yates Coaching, and rides between 10-15,000 km a year, using an electric bike when the terrain dictates.

"I do some eight-hour rides sometimes. I’ve had heart issues for a number of years, which have been making me slow down a bit," he says. Pacemaker-fitted Yates has had two strokes and has an atrioventricular canal defect.

If you subscribe to Cyclingnews, you should sign up for our new subscriber-only newsletter. From exclusive interviews and tech galleries to race analysis and in-depth features, the Musette means you'll never miss out on member-exclusive content. Sign up now

Formerly the editor of Rouleur magazine, Andy McGrath is a freelance journalist and the author of God Is Dead: The Rise and Fall of Frank Vandenbroucke, Cycling’s Great Wasted Talent and Tadej Pogačar: Unstoppable.