Where are they now? Lance Armstrong’s 1999 Tour de France US Postal team

The main players in the infamous squad, 25 years on from the Texan's first yellow jersey

A quarter of a century has passed since the 1999 Tour de France, which promised a new era for the sport of professional cycling. It delivered, but not the way it set out to do.

The 1999 edition was dubbed the ‘Tour of Renewal’, coming 12 months after the Festina scandal had shaken the sport to its very foundations. Widespread doping within the peloton had been laid shockingly bare and, after the 1998 Tour somehow made it all the way to Paris, the sport was supposed to have turned the page and started on a fresh, clean, slate.

How farcical that now seems. The 1999 Tour de France was the first in a run of seven successive Tours that do not have a winner. The man standing in yellow atop the podium in Paris on all of those occasions was, of course, Lance Armstrong, the cancer survivor who wrote a story that was, it turned out, too good to be true.

A lot has changed in the past 25 years. Armstrong’s eventual confession to doping, after years of whistles blown, investigations pursued, and lawsuits lodged, sent shockwaves through the sport. The riders on that US Postal squad for the 1999 Tour were all, to differing degrees, caught up in the storm.

But how have they landed now the dust has settled? How do they fill their days? And how are their relationships with not just with Armstrong but with cycling?

There were nine riders on the team – “an odd bunch”, Armstrong once said – and one infamous team manager. Here’s what they’re all up to in 2024.

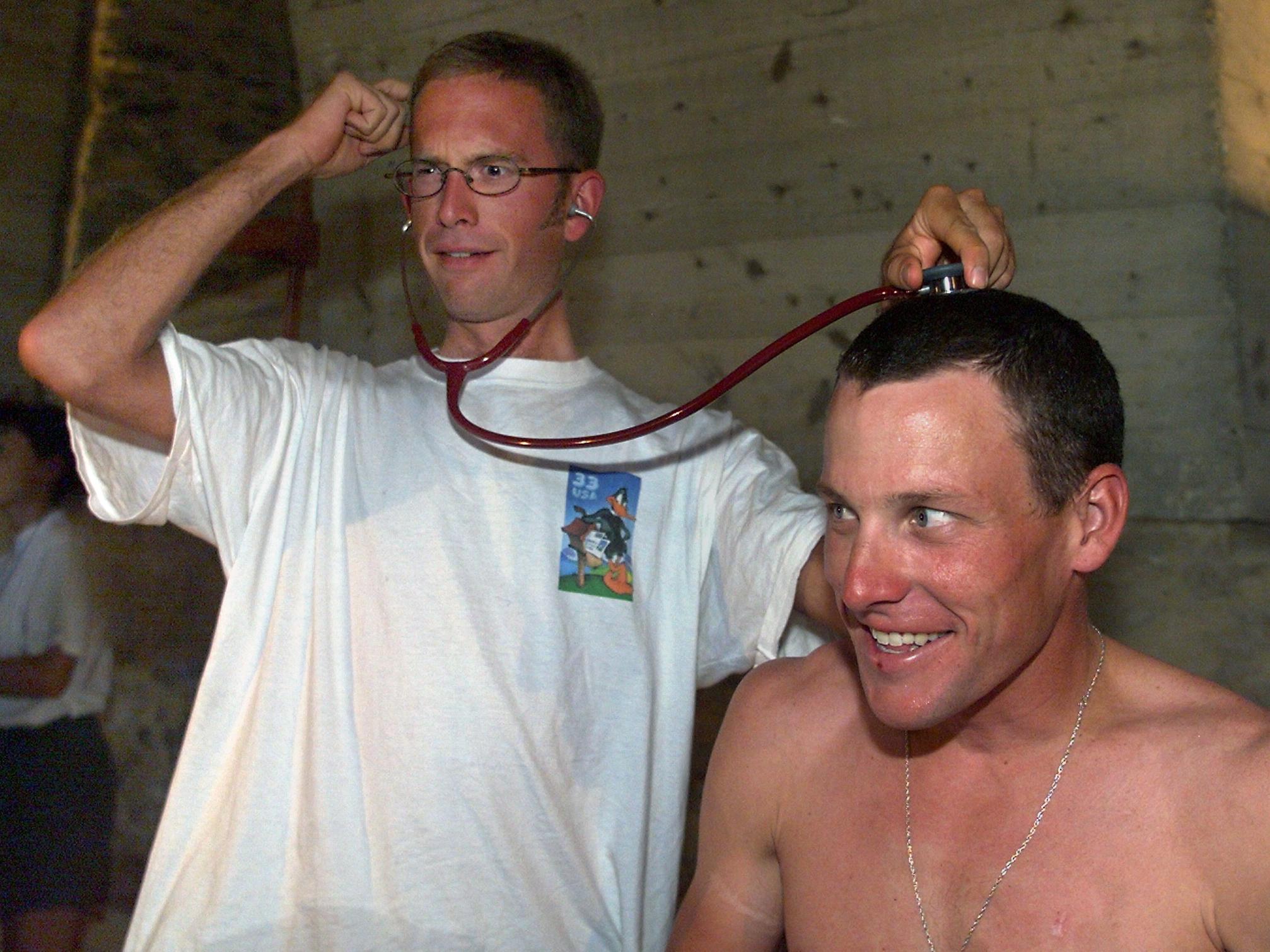

Lance Armstrong

The rider at the heart of it all needs little introduction. He is the most famous cyclist of all time, his rise and fall making for one of the most extraordinary narratives in sporting history.

Armstrong remains banned for life from professional cycling, and while he might have spent several years in the wilderness, fighting lawsuits and flirting with financial ruin, his rehabilitation has gathered pace in recent years, most notably through the launch and growth of his podcast operation. The podcast is named The Move, and currently sits as high as fifth in the US sport podcast charts, but it’s part of a wider stable named WEDU, a company founded by Armstrong in 2016.

It was a different podcast, The Forward, that kick-started the whole thing, with Armstrong insisting he didn’t want to make a cycling podcast and going out to interview figures from the wider world. However, the output there has become more sporadic as The Move, very much a cycling podcast, has taken flight in the past few years. There are spin-off shows, camps in destinations such as Mallorca, and a healthy array of sponsors.

WEDU, which stands for ‘we do’, was conceived as a community for endurance sport enthusiasts, and also features two sportives in the US, the Aspen Fifty and the Texas Hundred. It’s one of Armstrong’s two main business pursuits, alongside Next Ventures, a venture capital fund that invests primarily in the health and wellbeing sector. Armstrong knows the potential of investment better than most; he credits an early purchase of shares in Uber with ‘saving’ his family, amid a claimed bill of $111m in lawsuit losses.

Sign up to the Musette - our subscriber-only newsletter

Armstrong still does some charity outreach, still trains extensively on and off the bike, and still has his bike shop in Austin, Mellow Johnny’s – a play on ‘maillot jaune’, seven of which are proudly displayed on the walls.

But it’s The Move that has thrust Armstrong back into mainstream public consciousness on a regular basis, and in that respect there has seemingly been a softening in public perception. It wasn’t so long ago that Armstrong was so disgraced no one would be seen near him. Pro cyclists would be deemed tainted by association and his appearance at a charity ride taking place a day ahead of the Tour de France in 2015 caused a huge controversy. Nowadays, current pros are regular guests on his podcast, from stars such as Mark Cavendish and Geraint Thomas to up-and-coming Americans like Matteo Jorgensen. Likewise, he has enough partnerships with brands not to be considered any kind of outcast.

So while his sins may never be forgiven, they are perhaps starting to be forgotten, the edge being chipped off the outrage, if only due to the gradual passing of time.

Tyler Hamilton

Tyler Hamilton has a cycling coaching business. So far, so very predictable. But the Montana native also has the most normal, real-person, job of anyone on this list. He’s a financial advisor. Or, to go full Linkedin, he directs investor relations at Black Swift Group. And so, in the hands of one of the most well-known cyclists of recent times, a profession that wouldn’t set many dinner parties alight suddenly becomes rather fascinating. Many former elite athletes go into business as entrepreneurs, but most don’t have the stomach for the suit and tie five days a week.

Hamilton had studied economics at college, dropping out to pursue his cycling career, but moving into finance was far from a clear-cut post-racing route. In fact, it took him a long time to figure out what to do, and at this point it’s worth circling back to his career and remembering Hamilton as something of a tortured soul. He was the most important rider for Armstrong in 1999, the highest-level lieutenant who would leave in 2002 to chase his own dreams, finishing runner-up at that year’s Giro d’Italia and fourth at the following year’s Tour. However, in 2004 he was found out for blood doping, losing an Olympic gold medal. While he did return to the sport following a two-year ban, he tested positive again and a new eight-year sanction ended his career in 2009.

Hamilton initially upheld the omertà but was subpoenaed as part of the US Postal federal investigation and that was the catalyst for an about-turn. Ever since, he has run like a tap, and it has proved hugely cathartic. Hamilton has been open about the fact he suffered from depression since his best days as a rider, and his whole post-racing life has been testament to the power of letting go of secrets and their baggage. After coming clean to his family and the media, Hamilton penned one of the most explosive sports books of all time, The Secret Race, which came out at a time when the walls were closing in around Armstrong, but little was known of the sordid behind-the-scenes details of daily doping. The book led to another secondary career, as a motivational speaker. That won’t have pleased some of the riders on this list, but there does seem to be an authenticity to Hamilton’s remorse, in that even now when you hear him speak, he still seems troubled by the past, the irony being that the one who has confronted it most directly has perhaps had the hardest time leaving it behind.

As the momentum drained from the speaking duties, Hamilton, alongside his coaching company, Tyler Hamilton Training, trained as a real estate agent in 2015 but soon realised he wasn’t cut out for it. It wasn’t until 2019, when he was approached by an old friend, that he entered the world of finance and investment, and he hasn’t looked back, regularly travelling from his home in Montana to Black Swift Group’s Colorado HQ to cultivate their client base.

Hamilton says he couldn’t face riding his bike for a number of years but has fallen back in love with it, albeit in a different way. He has taken bike packing trips all over the world, and now many of his pedal strokes are spent pulling a trailer containing his three-year-old son from his third marriage. Yoga and meditation also help to keep his mental health in shape.

Pascal Deramé

An internet search and a social media scan sheds no light on how Pascal Deramé fills his days. Our approach via a phone number we dug out remains unanswered, and our enquiries with French cycling insiders yield little progress, either. “He vanished!” says one.

The sole Frenchman on the line-up had a relatively low-key career, retiring after seven years and with one victory to his name. He was a pure domestique, signed ostensibly to add a French ally for Jean-Cyril Robin in 1998, but proving a useful workhorse for Armstrong in 1999, although he’d leave for French team Bonjour by the turn of the season.

Deramé hung up his wheels after the 2002 season and has faded into the background. He remained involved in cycling at a lower-level in France, becoming a director of the long-running U Nantes amateur team in his native Brittany, with a particular focus on developing young talent. He reportedly joined on a voluntary basis at first, before taking up a salaried position, so the love for the sport must have still run deep.

Sadly, he was dismissed in 2017 after more than 15 years of service, as the team faced financial issues. Either the team cut the rider roster or got rid of a director and, as the highest paid, Deramé was the fall guy. “I prefer to hang onto the good memories of the moments we shared, the super guys I met, and a sponsor faithful to cycling,” he told Ouest France.

However, a journalist for that same newspaper informs us that Deramé took it heavily, and cut all ties with cycling. Apparently, he attempted to open a supermarket on the outskirts of Nantes, but didn’t manage to get the project off the ground. He’s said to be living somewhere among the vineyards of Nantes.

George Hincapie

George Hincapie forged a reputation as Armstrong’s sidekick, and that remains the case to this day. He was the only rider by the Texan’s side for all seven of his Tour de France ‘victories’, and he’s now his business partner and co-host of The Move.

With a bigger, heavier physique, Hincapie was more of a Classics specialist, who podiumed Paris-Roubaix and the Tour of Flanders and won three US road race titles. As such, he was deployed in the versatile rouleur role and his importance was underlined by his list of races in Armstrong’s service. In fact, only one rider in history has ridden more Tours than his tally of 17. After Armstrong’s initial retirement, Hincapie helped Alberto Contador to Tour de France glory in 2007, before linking up with the up-and-coming Mark Cavendish at Columbia, and then landing another yellow jersey with Cadel Evans at BMC in 2011. He finally confessed to doping in 2012 following the publication of the USADA Reasoned Decision, although he claimed he had raced clean after 2006.

He has gone on to launch several business ventures, most notably alongside his brother, Rich, a business graduate. Most revolve around cycling, but the pair also opened a luxury guest house in South Carolina, named Hotel Domestique, which in fairness still brings it back to cycling. Rich had already established Hincapie Sportswear, a cycling apparel brand, in 2003, and George joined forces once retired. The brand would be the title sponsor of another joint initiative, a US-based cycling team established in 2012 as a feeder team to BMC Racing. Despite blooding the likes of Toms Skujins and Joey Rosskopf before rising to ProContinental status in 2018, the pandemic was a crushing blow for the set-up and its prospects of competing in Europe, and so it was shut down in 2020.

The Hincapies have since added another arm to their eponymous brand, in the form of a series of Gran Fondos, which now counts five events throughout the USA. Remarkably, one of George’s two sons, Enzo, won the Chattanooga event in 2022 at the age of just 13. His father rode as a luxury domestique that day, and still rides his bike extensively, whether it’s in South Carolina or on the road with The Move.

In short, George is hardly twiddling his thumbs, and the Hincapie name could well reverberate around the cycling world for years to come.

Jonathan Vaughters

Jonathan Vaughters did not play much of a part in the 1999 Tour de France, crashing out on stage 2 as the peloton split on the exposed tidal road that links the island of Noirmoutier with mainland France. However, he has since enjoyed the most prominent role within professional cycling of anyone in the squad.

Vaughters is the general manager of the EF Education EasyPost team, who are currently racing their 17th consecutive Tour de France – a success story in itself. His reabsorption back into the centre of the fold still appears to irk those who are forced to watch on from the sidelines, and it’s safe to say the wounds have never healed. After his retirement in 2003, Vaughters reinvented himself as an anti-doping activist, which has earned him respect in some quarters and derision in others: just last week he was branded a “hypocrite clown” by Johan Bruyneel, the boss of US Postal in 1999 (more on him shortly).

In any case, Vaughters went to found the Slipstream Sports set-up, taking it from a small US operation to a 2008 Tour de France debut with a clean philosophy and another rider on this list, Christian Vande Velde, who would finish fourth at that year’s Tour.

Vaughters took the team to the WorldTour the following year and they’ve remained there ever since, which is quite something given his status as a leading voice in calling out the dysfunctional economic ecosystem of pro cycling. The team came very close to folding in 2017, just after Rigoberto Urán finished runner-up in the Tour. The stress of trying to save it, which involved a crowdfunding campaign, was partly to blame for the collapse of his second marriage, according to Vaughters, who also pointed to his diagnosis of autism the following year.

Vaughters has never had the financial freedom of the biggest teams, but his longevity is surely testament to a certain resilience and innovative streak. He has largely had to resort to 'moneyball' signings and while results have been mixed, there’s no arguing with the success of EF’s ‘alternative’ calendar, which has seen the popular free spirit Lachlan Morton headline a feel-good tour of two-wheeled adventures beyond the confines of the elite pro road scene. It’s no exaggeration to say the initiative has reimagined what sponsorship activation and athlete engagement look like in the modern day, and while Vaughters remains a divisive figure, few would argue his team lacks personality or identity.

Vaughters splits his time between his European base in Girona, Spain, and his home city of Denver, Colorado, where he houses a cellar dedicated to his primary non-cycling passion: wine.

Peter Meinert-Nielsen

One of only two non-US riders on the squad, Peter Meinert-Nielsen became a sports director in retirement, and works in cycling now, but wait until you hear what he did in between. He was a kitchen salesman. In 2004 he ran a store of the Hanstholm chain of luxury kitchens and homeware. The store closed down but he spent the last few years of his tenure operating out of his own home in Torring.

Meinert-Nielsen was the oldest of the 1999 US Postal Tour de France squad, at 33 and with 12 Grand Tours already under his belt. That Tour was to be his last, and he still regrets not finishing it, a crash ruling him out on stage 13. He joined the Danish team Fakta in 2000, in what proved to be his final season sue to waning motivation. In retirement, he moved straight into a management role at Fakta. That was until he got into kitchens.

He had a short second stint as a DS with Blue Water in 2013 but the following year he would start the occupation that keeps him busy to this day: helping get more people into cycling. Meinert-Nielsen works as a consultant for the DGI, a non-governmental association of amateur clubs in Denmark, which aims to increase sports participation at grass roots level. He operates in the Jutland region, putting on rides, offering guidance, and helping cycling clubs boost membership numbers.

Meinert-Nielsen has also started appearing as a pundit on Discovery’s cycling coverage in Denmark, but he still leaves plenty of time for riding his bike. Gravel is his thing now, and he’s also partial to a spot of bikepacking and cyclo-tourism. Whatever it is, he lives for it, as a quick scroll through his Instagram will tell you. He describes headwinds as “lovely” and gravel riding as “pure conditioner for the soul”. Now there’s a man who’s still in love with the bike.

Christian Vande Velde

US cycling fans will likely be familiar enough with Christian Vande Velde, given he’s on their screens every day this month. Remarkably, the Chicago native has already racked up a decade’s worth of broadcasting experience, appearing as an analyst on NBC’s Tour de France coverage for the first time in 2014, the first year of his racing retirement. Since then, he has become an authoritative voice for US viewers, although these day’s he’s found mostly on a motorbike, doing the roving reporting role from within the peloton.

Vande Velde was only just getting going when he lined up for the 1999 Tour as a 23-year-old second-year pro, and he has described a blissful sort of naivety as the whole experience washed over him and the magnitude of it escaped him. He only rode one further Tour for Armstrong before leaving for Liberty Seguros in 2004 and then finding his feet at CSC. It was under the guidance of 1999 Tour teammate Vaughters, however, that things really clicked, as he blossomed into a GC rider with Slipstream/Garmin, placing fourth at the 2008 Tour de France and eighth a year later.

The latter years of Vande Velde’s career were blighted by crashes. He confessed to doping following the publication of the USADA Reasoned Decision in 2012, but claimed he had "started racing clean again well before joining Slipstream". He served a six-month ban before seeing out a short final season in 2013.

Still, Vande Velde was not deemed persona non grata. He was quickly snapped up by NBC and threw himself into a number of other projects, including rider representation for the CPA riders’ union, with a focus on the US continent.

He soon signed up with Peloton as a celebrity coach, leading virtual indoor training sessions for the exercise bike brand. However, he stopped early in 2020 to launch his own training platform, an app named The Breakaway. Founded alongside two former Strava employees, it takes users’ data to create, with the help of AI, tailored training plans. The app is going strongly but Vande Velde recently announced his return to Peloton as a guest instructor.

Vande Velde moved to South Carolina after leaving his European base of Girona in retirement, and can regularly be seen out riding with Hincapie.

Kevin Livingston

Kevin Livingston was a close friend of Armstrong, and is so again now, but their relationship suffered a notorious blip. Livingston, who’d been headhunted to join US Postal in 1999 after riding with Armstrong at Motorola, deigned to move on after just two seasons and two Tours. What’s more, he wound up working for Armstrong’s arch-rival, Jan Ullrich. Livingston had intended to join the Linda McCartney team after asking for more money and more freedom, which already irked Armstrong, but when that fell through, he ended up doing what Armstrong likened to US Army general Normal Schwarzkopf defecting to communist China.

The pair did re-build their bridges in the wake of Livingston’s shock early retirement after the 2002 season. Livingston continued to live in Armstrong’s hometown of Austin, where he’d moved during their Motorola days. He even opened a base for his retirement project, the Pedal Hard coaching company, in the basement of Armstrong’s bike shop, Mellow Johnny’s. For many years, Livingston operated out of this centre, which included an indoor training hub and a Retul-equipped bike fitting service. This, however, has now shut down.

Livingston also worked with the Trek-Livestrong U23 team and has been involved in race organisation for events in the USA. However, he has consistently kept a low profile, the only sign of him on social media being the roller skiing (a drylands form of cross-country skiing) activities – and the occasional ride – he uploads to Strava. We were unable to get hold of him for this piece and, in his recent biography of Jan Ullrich, Daniel Friebe recounts his own efforts to track Livingston down, which went as far as turning up at Mellow Johnny’s unannounced.

“I spot a shop clerk, tell him why I’m here, to which the colleague responds that he’ll go and fetch Kevin. A minute or two later, the same gentleman returns to uneasily tell me that, no luck, it turns out Kevin’s not around. When I relate all of this to Armstrong the next day,” Friebe continues, “he shakes his head. ‘I don’t get it,’ he mutters. His efforts to solicit Livingston on my behalf come to nothing.”

Frankie Andreu

Armstrong has turned on most riders on this list in one way or another, and while bonds may have been repaired among most, the bridges that were burned between him and Frankie Andreu are as good as irreparable. Andreu and his wife, Betsy, are best known as whistleblowers in the whole saga and while it’d take too long to go over the whole affair here, suffice to say it got very, very ugly.

Andreu was an elder statesman of the 1999 Tour squad, a 32-year-old who had already ridden seven Tours. He’d ridden with Armstrong at Motorola, and played an important road captain role but only for two of the ‘victories’, retiring in 2000, although he did dabble as an assistant team director in 2001 and 2002.

Andreu has made a name for himself with microphone in hand, and that started on Universal Sports’ Tour de France television coverage, where he was cast in a reporter role and, somewhat bizarrely, made his way around the buses trying to grab words with, among others, his former teammates.

Andreu did make attempts to get into team management but never had much luck, partly because, he says, of the whole Armstrong affair. He was fired from Toyota-United in 2006, which he pointed out coincided with the controversy surrounding his testimony, and he only lasted several months at the ill-fated Rock Racing set-up. He then managed five years as DS at the Kenda Pro Cycling team but suggested in his USADA affidavit they weren’t getting race invites due to his feud with Armstrong. “I have been told that my public disputes with Lance Armstrong have made it more difficult for others in the cycling industry to work with me because they fear reprisal from Lance and his associates,” he stated.

Andreu has instead thrown himself into his broadcasting. Despite no longer being a part of TV Tour de France coverage, he has established a successful announcement and commentary business, Andreu Racing LLC, which sees him perform as the official speaker for a number of events, from US crit racing and Gran Fondos to running events and triathlons. He performs the master of ceremonies role pre and post-race, as well as often commentating on live streaming coverage, and judging by his schedule, he’s not short of work.

Johan Bruyneel

Pulling the strings of this nine-man squad was the infamous Johan Bruyneel, a Belgian team director inextricably linked with Armstrong’s rise and fall, and by extension with the very worst of cycling’s doping excesses. In fact, his name still seems to carry super-villain connotations, not quite in the ‘he-who-must-not-be-named’ manner of a Michele Ferrari, but not far off. That’s because, like Ferrari and like Armstrong, he is banned from the sport of professional cycling for the rest of his life.

Bruyneel was initially handed a 10-year ban, but halfway through it was upgraded to life, although he appears to have avoided the worst of the million-dollar financial impact of the US lawsuits by virtue of living abroad, calling Madrid home for a number of years. Nevertheless, Bruyneel has opened up about the toll of the fallout from the scandal, saying his physical and mental health declined as he hit “rock bottom”. His close alliance with Armstrong was undimmed and if anything the pair grew closer. “When I was in really deep trouble – and there were many times when I was in really deep trouble – he was there, unquestioning and without hesitating: 'What do you need?’,” Bruyneel told the Dutch journalist Raymond Kerckhoffs in 2020. “I think that that reinforced our bond.”

Bruyneel remains closely linked to Armstrong in business, as a central member of the Wedu operation. He regularly appears on The Move, has his own spin-off podcast JB2, and hosts the Spanish version – La Movida – in perfect Spanish. For those who don’t listen to those podcasts, Bruyneel sits most prominently in the public imagination for his output on X (formerly Twitter), where his bio sets out his stall in no uncertain terms: “Calling out bullshitters and hypocrites.”

Vaughters, as we’ve touched upon, is a favourite target in this regard. As recently as last week, it was revealed that the EF rider Andrea Piccolo had been stopped at a border on suspicion of trafficking human growth hormone (itself a throwback to the old days), with Vaughters showing the media a text message from the rider. “LEAKY Jonathan Vaughters has been at it again, doing what he does best: leaking private and personal messages to save his own ass,” cried Bruyneel.

Few are safe from Bruyneel’s cynical, scathing barbs. The World Anti-Doping Agency and UCI president are regularly taken on, but there are also a few more surprising hits, such as a recent insinuation against the former Belgian world champion Philippe Gilbert and a somewhat bizarre eagerness to undermine the Gen-Z social media commentariat. The latter in particular, whether he has a point or not, adds to a look that gives frustration and insecurity. Professional cycling mostly seems to irritate Bruyneel, and yet he remains resolutely attached to it, bitterly suckered to the perspex window. When he’s looking in on so many of his fellow former sinners, can you really blame him?

If you subscribe to Cyclingnews, you should sign up for our new subscriber-only newsletter. From exclusive interviews and tech galleries to race analysis and in-depth features, the Musette means you'll never miss out on member-exclusive content. Sign up now

Patrick is a freelance sports writer and editor. He’s an NCTJ-accredited journalist with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages (French and Spanish). Patrick worked full-time at Cyclingnews for eight years between 2015 and 2023, latterly as Deputy Editor.