When is a positive not a positive? COVID-19 and the Tour de France

Chances of false results are high unless ASO do repeat testing on COVID-19 positives

Disclaimer: The coronavirus pandemic is a serious problem and COVID-19 has led to over 800,000 deaths worldwide. There is no doubt that people should be taking every precaution to keep from spreading SARS-CoV-2. This information is not meant to contradict public health policy or inform medical decisions. It only applies to situations where COVID-19 infections are expected to be very low such as the Tour de France bubble, so wear a mask, wash your hands, and stand clear of the riders, please.

The stakes are high for this shortened season of professional cycling. If COVID-19 spreads at the Tour de France, the consequences will be dire for the ASO, the UCI, the racing season and the population.

However, riders have already had issues with potential false COVID-19 positives and will undergo at least four PCR tests before and during the race. When, not if, a rider falsely turns up positive for the virus, the consequences will fall not on the ASO or UCI but on the teams, staff and riders.

The ASO and the UCI have meticulously prepared strict sanitary measures for the race, including pre-race monitoring and testing in hopes of keeping the virus away. But this level of sanitation counterintuitively makes interpreting a positive COVID-19 test more difficult.

Will the Tour de France have a positive? Possibly. Can we be sure one positive is accurate? Probably not.

Alpes-Maritimes, the region where the Tour de France will start is in a red zone, having crossed a threshold of confirmed infections with 5.5 per cent of tests confirming COVID-19 and 97 per 100,000 residents testing positive every day.

However, inside the 'team bubble' - all people who will be healthy with no symptoms of COVID-19, and who have been meticulously avoiding the public, wearing masks and washing their hands - the chances of that positive being wrong are alarmingly high.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

ASO's written policy is to require any rider or staff member testing positive once to leave the Tour, even if a subsequent test is negative and they have no symptoms. An ASO spokesperson said this policy is "what the health authorities ask of us".

But they might want to take a cue from other professional sports.

The NBA, which had issues with possible false positives before creating their 'bubble' in Orlando, instituted follow-up tests for any players testing positives to rule false positives out. After Detroit Lions quarterback Matthew Stafford turned up a false positive on July 31, the NFL announced it would do two follow-up tests on all positive asymptomatic individuals. Since then, they detected 77 false positives, all relating to the same laboratory in New Jersey.

The Tour de France's mobile environment makes follow-up testing trickier, but if the ASO did immediate follow-up tests (after publication of this article, they announced they would), the chances of getting back-to-back false positives would be far smaller.

Cyclingnews spoke to Ranga Sampath, PhD, the Chief Scientific Officer with the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), a non-profit that conducted independent evaluations of almost 800 different COVID-19 diagnostic tests.

Sampath explains that no test is perfect and human error and problems with testing materials will always lead to some level of mistakes. "Any test has a low but not improbably chance of false positive," he says. "Even a test that is more than 99 per cent specific."

Most of the COVID-19 tests are highly specific in controlled laboratory tests but we don't know the actual rate of false positives in their real world use. Sampath says there is no such thing as a 100 per cent perfect test.

"If someone claimed 100 per cent specificity, I would not believe them. A test is not going to be 100 per cent all the time. You're battling the improbably odds of never being wrong."

COVID-Catch-22

From a public health perspective of stopping the spread of disease, diagnosing someone as COVID-19 positive when they don't really have it (false positive) is less of a concern than missing infections (false negative) and having them spread. But false positives can also wrongly put healthy people in isolation, cause undue stress and possible loss of income.

Dr Andrew N. Cohen of the Center for Research on Aquatic Bioinvasions has been vocal in his criticism of ignoring the importance of false positives and the global strategy of diagnosing COVID-19 based on a single positive test in the absence of any symptoms.

His own research led him to medical literature from previous pandemics - SARS-CoV-1, MERS, Ebola. For those diseases, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommended testing only people with symptoms or known contacts with confirmed cases. For SARS-CoV-1, they specified "a single test result is insufficient for the definitive diagnosis of SARS-CoV infection".

That all changed with COVID-19.

"The more data we get, the clearer that seems to be. Some of this is coming from the sports world, but a lot of it is coming from other places where people do a second test and check positive results, and they find a substantial portion of them are false positive," Cohen tells Cyclingnews.

"What we're saying is certainly out of the mainstream for what has been said for SARS-CoV-2, but it's completely in the mainstream for what the CDC and WHO and medical professionals have said up through 2019 about using PCR-based diagnostic tests, which is that they have a certain rate of false-positives, you need to watch out for them."

When you're testing people who are sick, there is invariably a greater proportion of them who will actually be infected with the virus, so in those cases, a positive result is more reliable. But when you begin testing large numbers of healthy people with no known exposure to infected people, the chances of any positive become so small that the chance of the result being falsely positive skyrockets.

The rate of false positives out of all of the tests done, Cohen says, is low - "down to 1 per cent or a fraction of a per cent, maybe 2 per cent in some places" but when the population you're testing is relatively free of COVID-19, "that's enough to have a substantial proportion of the positives be false positives. It's not intuitive - but that's how the statistics work out."

Sampath agreed with Cohen's logic, saying this is something that is considered in any diagnostic test and he also recommends follow-up testing.

"It's basic statistics: even with a highly specific test, if the prevalence of the virus is low, the chance of a false positive becomes high. Repeat testing is the only way to rule out a false positive," Sampath said.

Base rate fallacy a.k.a. False-positive paradox

The same math could explain the spate of positive results in recent weeks that have hit professional cycling.

Before the Vuelta a Burgos, Itamar Einhorn came back positive, and Israel Start-Up Nation pulled riders off the start line. Silvan Dillier (AG2R La Mondiale) was kept out of Strade Bianche, his teammate Larry Warbasse removed from the team's Tour du Limousin roster, Hugo Houle (Astana) sat out Il Lombardia, Inge van der Heijden was kept from the Dutch championships and Bora-Hansgrohe prohibited from racing the Bretagne Classic when Oscar Gatto tested positive.

What do they all have in common? Subsequent tests came back negative.

It's possible that these healthy athletes battled the virus so quickly that they never showed symptoms and their bodies eradicated it soon enough that their follow-up tests came back negative, but Houle also had a test for antibodies that might pick up evidence of a past infection - that too was negative.

Did they have COVID-19 or not? The answer to this puzzle might lie in the "base rate fallacy", also known as the "false positive paradox": The closer the baseline rate COVID-19 infection gets to the rate of falsely positive tests, (FPR) the less confidence we can have that any positive test is really picking up the COVID-19 virus.

Most people think that if the chance of getting a false-positive result is 1 in 1,000, then any positive result is 99.9 per cent true. That isn't the case, because you have to factor in the rate of infection in the population. If the infection rate is 1 in 1,000 and the chance of a false positive is the same, 1 in 1,000, then the chance a positive result is true is a coin flip - the positive could be real, or it could be false - 50-50.

Take 100,000 people, and assume 100 have COVID, and test them all. Up to 20 per cent of the tests can miss an active infection (either because people are tested too soon after exposure or they don't stick the swab up their nose far enough) and be a false negative.

Let's say that the lab being used is pretty good at their job and only 1 in 1,000 tests is a false positive.

Eighty COVID-19-infected people will be correctly identified, 20 will not because of false negatives. Of the other 99,900 healthy people, around 100 will test positive even though they aren't infected and 99,800 will be negative.

Just looking at the positives, there are a total of 180. 80 are correct and 100 are not! Only 44.4 per cent (80 of 180) of the positives were correct. That's the "Positive Predictive Value (PPV)".

| Header Cell - Column 0 | Has COVID | Healthy | Total | PPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive test | 80 | 100 | 180 | 44.40% |

| Negative test | 20 | 99800 | 99820 | 100.00% |

| 100 | 99900 | 100000 | ||

| (20% false negative rate) | (0.01% false positive rate) | 0.18% of tests positive | Row 3 - Cell 4 | |

| Row 4 - Cell 0 | Row 4 - Cell 1 | Row 4 - Cell 2 | Row 4 - Cell 3 | Row 4 - Cell 4 |

| Row 5 - Cell 0 | Chance you have COVID | Chance you don't | Row 5 - Cell 3 | Row 5 - Cell 4 |

| If test result is positive | 44.4% | 55.6% | Row 6 - Cell 3 | Row 6 - Cell 4 |

| If test result is negative | 0% | 100% | Row 7 - Cell 3 | Row 7 - Cell 4 |

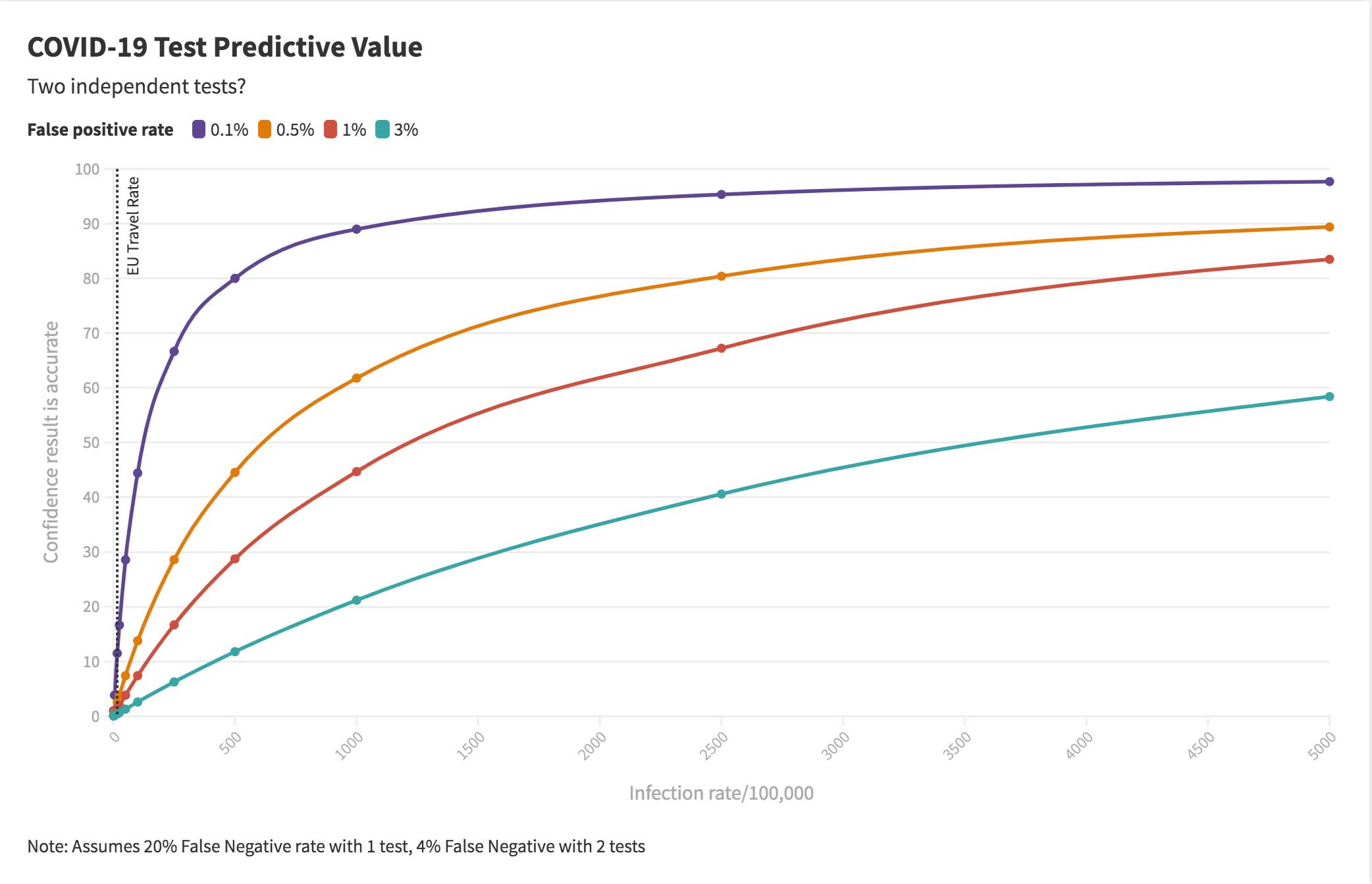

The graph at the top of this section highlights the relationship between overall prevalence of the virus in a population and how much confidence we can have in a test given four different false positive rates.

The more careful the team bubble is to be virus-free, the less confidence we can have in any positive test.

Only 18 in 1,000 of the samples are positive in this example. The Tour de France team bubble will have at least that many tests.

| Header Cell - Column 0 | Have COVID-19 | Healthy | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actual status | 100 | 99,900 | 100,000 |

| First result positive | 80 | 100 | 180 |

| Second result positive | 64 | 0 | 64 |

| Second result negative | 16 | 100 | 116 |

| First result negative | 20 | 99,800 | 99,820 |

| Second result positive | 16 | 100 | 116 |

| Second result negative | 4 | 99,700 | 99,704 |

| Chance person has COVID | Chance person COVID-free | ||

| Two positive results | 100.00% | 0.00% | |

| Two negative results | 0.00% | 100.00% | |

| One of each | 13.8% | 86.2% |

Credit: Stan Brown/BrownMath.com

If you do a second test to confirm the positive, the chances of getting a false-positive plummets because now you have two independent tests on the same person with the same outcome. One can be nearly 100 per cent confident of two identical results, but only there's a 13.8% chance the person is actually COVID-19 infected if they have one of each.

Even with one positive is followed by one negative, it's 97.6% likely the person doesn't have COVID-19 if the infection rate 100 in 100,000. Even if it's tenfold higher, one of each still casts doubt on a single positive.

This simple mathematical certainty is why the NBA and NFL added in a second PCR test for every positive to rule out false positives.

Cycling has chosen a safety-first policy, which is commendable. But if a rider or staffer who tests positive can have a rapid re-test then it would prevent quite a few people unnecessarily ejected from the race.

Both Cohen and Sampath recommend the Tour de France do double tests on anyone who comes up positive for COVID-19.

"If I were running the show, I'd think about setting up two swabbing stations, a few hundred yards apart, with separate staff, for riders' left and right nostrils (although I might check to see if there are any studies on the probability of having detectable virus in one nostril but not the other), sending the specimens by different couriers to two different labs that use two different assays and running both specimens (or if timing allows, running the second only if the first is positive). That's about as independent as one could get," Cohen says.

"It would be good data too. Over the multiple testings during the race, they'd likely detect at least a few false positives, thereby gathering important information on the false positive rate in actual practice. Protect the Tour and contribute to medical science—what could be better?"

Laura Weislo has been with Cyclingnews since 2006 after making a switch from a career in science. As Managing Editor, she coordinates coverage for North American events and global news. As former elite-level road racer who dabbled in cyclo-cross and track, Laura has a passion for all three disciplines. When not working she likes to go camping and explore lesser traveled roads, paths and gravel tracks. Laura specialises in covering doping, anti-doping, UCI governance and performing data analysis.