Whatever happened to: Rock Racing 2008

Michael Ball's edgy team shook up the cycling world but burnt out fast

Professional cycling is steeped in tradition and has a whole playbook of unwritten rules and norms, so when clothes designer and entrepreneur Michael Ball broke onto the scene with flashy kits, big black Cadillacs, fashion models and brash attitude with the Rock Racing team, he shook up the sport.

The riders who helped found the team, however, remember the years 2007-2009 fondly – in particular the tight-knit group of Southern Californians who made a name for Ball's Rock & Republic brand on the cycling scene.

The team was a bit like the Icarus myth. Ball signed on convicted dopers and blacklisted Euro pros who were rejected after the Operacion Puerto scandal: he tried to build the team up too high, too fast and, in the end, it crumbled around him.

The 2008 season was the peak of mayhem for Rock Racing: from the temporary comeback of Mario Cipollini, to the Operacion Puerto refugees Santiago Botero, Tyler Hamilton and Oscar Sevilla, being excluded from racing at the Tour of California and riding defiantly and somewhat dejectedly ahead of the race in protest.

Since the team's disappearance, pro cycling has felt a little more staid, a touch more conservative. Rock Racing rolled into races with outrageously expensive vehicles, swapped gaudy team-kit designs for gaudier team-kit designs, and generally made a splash wherever they went.

Cyclingnews found a few of the former riders to tell their stories.

Rahsaan Bahati

Bahati made a name for himself at age 18 when he won the USA Cycling Criterium national championships for elites. He went on to race for big teams like Saturn before landing back in LA with the McGuire-Langdale squad, making $500 a month and living on prize money.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Then, he scored a top 10 in a now-defunct big one-day race in Trenton, New Jersey and earned a berth on Jonathan Vaughters' TIAA-CREF squad – the predecessor to Slipstream and EF Pro Cycling.

But Bahati felt he wasn't given a chance to develop and he ended up packing his bags and heading back home. He tried dabbling on the track, racing a qualifier for a chance to race on the national team at the World Championships. He won the Scratch Race only to be disqualified for dipping below the blue band and missing his shot.

"So after that race, I was kind of just packing my stuff up and a friend of mine named Haldane Morris came over and said, 'I want to introduce you to someone,' and it was Michael Ball," Bahati recalled to Cyclingnews.

"I had a big afro at the time. [Ball] just thought it was the coolest thing. He said he wanted to sponsor me, and you know, as a cyclist, you hear that all the time." But he decided to head to Ball's office for a meeting to see what he had to offer.

"I rolled up – I had a little Audi and thought I was cool – and my $16,000 car and I roll up to his office and it's nothing but Bentleys, Lamborghinis and Ferraris everywhere. It was just, like, out of this world."

Ball, a fashion designer, was also a recreational cyclist and racing enthusiast and wanted to invest in the sport. Bahati says he suggested several different levels of sponsorship and, of course, Ball wanted only the best and picked the highest budget – about $1 million – and they soon got to work hiring riders and building the team.

"Half of the group was close friends and, to be 100 per cent honest with you, on paper, they were not really good bike racers. We were just a good group of people together and the team meshed very well."

They meshed so well that they quickly got results against some of the most established teams in the country.

"We won the CSC Invitational in Arlington, Virginia. It was super hot that day. The reason that was big is because no one respected us. We were just this team that had a bus and these huge Cadillacs.

"Michael Ball didn't believe in skin suits. I ran into Hilton Clark getting ready for the start and he says, 'You can't win today; you don't have a skin suit.' So if you look at the photo of me winning that race, I'm pumping my hand and I'm saying, 'No skin suit!'"

Success built on success, but Ball decided he wanted bigger names, and to be invited to the Tour of California in 2008. He hired Tyler Hamilton, Oscar Sevilla, former Lance Armstrong domestique Victor Hugo Peña and Santiago Botero. He even brought Mario Cipollini out of retirement only for their relationship to soon turn sour after the Tour of California.

Bahati didn't agree with the decision, and fell out with Ball and ended up relegated to racing on the amateur team before the team folded and he created his own Bahati Foundation team. But that, too, got swept up – this time in the Floyd Landis/Lance Armstrong doping allegations. Since then, Bahati has continued to race and win and now works for Zwift.

Jeremiah Wiscovitch

Before Rock Racing, Jeremiah Wiscovitch was an all-rounder who raced for So Cal teams like LeGrange, Seasilver and SC Velo, but he admitted to being a jack-of-all-trades but master of none.

"I don't think I could do anything amazing, but I could do everything pretty well. I could climb with the best, but I'm not going to win a mountaintop finish. I could sprint with the best of them, but I'm not going to win a bunch sprint, but I can consistently be top five with the best guys. I was a pretty good breakaway rider," Wiscovitch tells Cyclingnews.

He signed on with Rock Racing in 2007 when it was still a band of locals and raced mainly as a domestique.

"Our first year, I think we even won a handful of races – maybe four or five of the big NRC races as kind of like a first-year underdog team. And it was kind of like a Cinderella story. We didn't think we could go up against these big-name teams and actually beat them. So we wanted to continue to grow that, but unfortunately we know who the owner of the team was and he didn't have much patience."

One day, he recalls, he was working for Sebastian Haedo (who would later race for Saxo Bank), and was given the green light to go for a sprint and impressed then-directeur sportif Frankie Andreu. But Andreu had a falling out with Michael Ball and left the team, and despite being only one of two riders from the team to finish Tour of Missouri in 2008, Wiscovitch found himself without a renewal.

"I've never been a very political person. I don't really buy into a lot of that stuff, and I'm not going to kiss asses and things like that, you know, so I just kind of call it how it is, and I don't think a lot of management liked that," he said.

Wiscovitch was already on the fence about being a pro bike racer before Rock Racing, struggling with being away from his family, and stopped racing after 2008. He went to school for nursing and now works as a critical-care nurse. He did a few races last year before his daughter was born, and even won a criterium in Ontario.

Currently, he spends his time treating patients suffering from COVID-19 and has been very concerned about the pandemic.

"I've been my entire career as a registered nurse and, you know, we see death every single time I walk in that unit. I'm confronted with death in different forms, whether it be a shooting, heart attacks or septic infections – you name it. But watching how fast these patients deteriorated was just mind-boggling to me. They would go from talking to us to four or five hours later being on full-fledged life support and getting everything we can throw at them just to keep them alive. It's been terrifying."

Cesar Grajales

Grajales came to the US from Colombia, like a number of his compatriots, looking to break into the scene. He won the mountains classification in the San Francisco Grand Prix in his first big race in 2003, then raced the World Championships with the Colombian national team in Hamilton, Canada.

He raced first for Jittery Joe's, and impressed on the climbs of Tour de Georgia, taking 10th overall in 2004.

"The highlight of my 2004 season was beating Lance Armstrong on the 'queen stage' in the Tour de Georgia, which proved to be a major turning point in my cycling career," Grajales tells Cyclingnews.

"Earning the respect of the cycling world was a defining moment for me as a cyclist. I then raced for Navigators Insurance for two years before returning to Jittery Joe's in 2007," he adds.

Following a training camp in the Blue Ridge mountains, Rock Racing directeur sportif Frankie Andreau reached out to Grajales.

"I was really excited to have the opportunity to work with him. With me, I brought fellow Colombian cyclists Victor Hugo Peña and Santiago Botero to the team."

Grajales rejoined Bahati on the Bahati Foundation/OUCH team in 2010, with Floyd Landis attempting his comeback with the squad.

"Friction that began between Lance and Floyd at the 2010 Tour de Gila resulted in our team being excluded from the Tour of California at Lance's direction," Gralajes says. "Had it not been for the support of [Canadian cycling company] Louis Garneau, our team would have lost all funding that year. After that, the team became Real Cyclists, and the following year the team became Competitive Cyclist. I did a couple of years with Stradalli Cycling, and eventually retired in 2015.

"Since then, I've kept pretty busy. In 2017, I took a motorcycle trip from Lyons, Colorado, to Colombia. I now own an excavation company, Highlands Hardscapes LLC, and live in Lyons, Colorado. Two years ago, I started a bicycle touring company, Caturra Bike Tours, providing road and mountain bike tours in my hometown of Manizales, Colombia.

"I was lucky to grow up in one of the world's most beautiful cycling destinations, and I enjoy showing people the real face of Colombia. As lead guide of Caturra Bike Tours, I get to share my passion for cycling with others in the very place that shaped me as a cyclist."

Kayle Leogrande

Kayle Leogrande is probably best known for his doping sanctions – the first that came in 2008 and a more recent case where he tested positive for seven different banned substances in 2017.

Before joining Rock Racing in 2007, Leogrande says he had been absent from racing for almost a decade before deciding to come back in 2004. He raced for Jelly Belly in 2005 but soon decided to spend more time building his tattoo shop, so he raced as an amateur for La Grange.

"I won elite Nationals that summer in 2006, and got a call from Rahsaan Bahati, who I was good friends with, explaining there was this guy in LA that wanted to meet me and that he was building a team. I laughed, saying, 'What the hell is Rock & Republic?!'

"I met with Michael Ball and he was a cool cat. He had a lot of energy and was eager to get a team put together but I could tell he didn't know what he was doing as far as building a cycling team was concerned."

But Leogrande just wanted to ride and said the first year was magical.

"I witnessed so many insane and, well, unbelievable things with my time on the team. I met Chris Cornell at a party Michael put on in Santa Monica. I met my now ex-wife at that very party. It was a very fast-paced two years on the team with me it was cool being teammates in 2008 with some of the sport's best athletes like Cippolini, Hamilton, Botero, Sevilla.

"What wasn't cool was making the 2008 Tour of California squad with the form of my life only to be sidelined along with others, and made to stick around for the week being tortured by watching the race take place and not being able to participate after all the training and sacrifice I had put into getting there.

"Bittersweet to say the least, but there were some good times and friendships I made that are still going, and I'm thankful for that, at least. Not many cycling teams allow the opportunity to be yourself unconditionally and to meet people you'd probably never meet. Michael was a friend and someone who enjoyed being around the riders he employed.

"Things got a little out of hand from the lack of organisation but, at the end of the day, I always had what I needed and always got paid to train and race my bike. You can't complain about that..."

Team soigneur Susanne Sonye told USADA in 2007 that she knew Leogrande was doping at Superweek that year, that he used testosterone and EPO, and tampered with a doping control. Leogrande attempted to sue USADA to prevent the B-sample analysis, and tried to sue Sonye for slander, but ultimately lost. The entire affair went on during Leogrande's tenure with Rock Racing.

After being banned for two years, Leogrande's orbit touched paths with Lance Armstrong's downward spiral when he left some EPO behind when he moved out of his apartment, and the owner called the Food and Drug Administration. Leogrande was questioned by Jeff Novitzky as part of the inquiry into Armstrong that was closed without charges. USADA, years later, went on to ban Armstrong for life.

Leogrande is three years into an eight-year ban for his second doping case and makes his living doing tattoos.

Adam Switters

Adam Switters was a promising junior, racing with the USA Cycling programme under Danny van Haute on the road and in cyclo-cross. He says he had some talks with Gavin Chilcott about joining BMC as it was getting started but didn't quite make the cut.

His berth on Rock Racing came about thanks to social media when he was 20 years old.

"I actually saw a tweet by Rahsaan Bahati (who I was friends with at the time) about a new team looking for some young riders," Switters tells Cyclingnews. "I quickly emailed him, and I think the next day I drove six hours down to LA to sign a contract. I was attending UC Davis at the time, so I think I missed a few classes to sign that contract."

When asked for his favourite memory from his two seasons with the team, Switters says there were too many to share.

"One of my favourites was the reality TV show that never aired. We had a whole crew following us around for two weeks during our training camp in Malibu. We were staying in these million-dollar mansions. Michael Ball was throwing out courtside tickets to Lakers games for winning sprints, $1,000 for KOMs... I think at the end of camp, we all just pooled our money together and came home with just under a grand each.

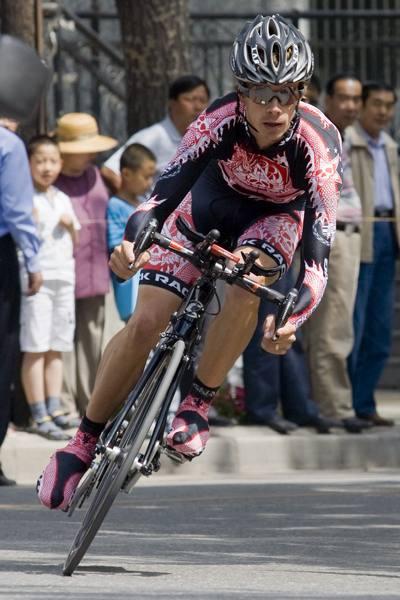

"Another favourite was the Vuelta a Colombia [in 2008, ed]. We had Botero, Sevilla, Hugo Peña and Hamilton all racing well. We travelled down there about 10 days early and stayed at Victor Hugo Peña's parents' place. He was so nice and his family was great. We were doing 20-30 mile climbs every day. Cycling in Colombia was crazy. Those guys are like rock stars down there.

"I eventually got my Masters in Kinesiology in 2015. I live in Folsom, CA. I'm currently working at Mercy General in Sacramento in Electrophysiology (ablation of cardiac arrhythmia and insertion of ICDs and pacemakers). I'm married with a two-year-old son, and have one more on the way."

Santiago Botero

Botero, winner of the polka-dot jersey at the 2000 Tour de France while racing for Kelme, won the 2002 time trial world championship and a trio of stages in the Tour and Vuelta a España.

Part of a wave of Colombian talent that emerged in the top tier, Botero signed with Kelme in 1996 and raced his first Grand Tour, the Vuelta a España, the following year. After racing the Giro d'Italia in 1998, Botero was on track for another Vuelta start after winning a stage of Paris-Nice, but ran into trouble with anti-doping controllers when his testosterone values measured at almost five times the allowed levels.

Then-team doctor Eufemiano Fuentes argued his levels were natural, but Kelme left him out of the team for the Vuelta. The Colombian federation eventually rejected Fuentes' arguments and banned Botero for six months.

Kelme welcomed him back once his ban was up, and gave him a start in the Tour de France in 2000, where he won the stage to Briançon and the mountains jersey. After winning more stages of the Tour and Vuelta and his world title, Botero moved to T-Mobile for a year before joining Tyler Hamilton on the Phonak squad.

He was booted off the team after being named as a client of Fuentes in the Operacion Puerto affair and returned home to Colombia where he raced 2007 with EPM-Orbitel. Cesar Grajales brought him into Rock Racing in 2008, and the team raced the Vuelta a Colombia, with Botero, Peña, Sevilla and Hamilton sweeping the prologue's top four.

When Ball tried to include Botero, Hamilton and Sevilla on the team's roster for the 2008 Tour of California, organisers AEG rejected their entry and the team was forced to race without them.

Botero finally called it quits in 2010 after racing two seasons for Orgullo Paisa in Colombia following a bout with dengue fever.

Mario Cipollini

Quite the fashion-conscious rider during his professional career, Mario Cipollini was a natural fit for Rock Racing. The only problem was he'd retired three years earlier. He was 41 when he signed on to race with the team at the Tour of California and it was clear that – despite a third place in one sprint stage – he was past his prime.

Cipollini had been lured to the team with the prospect of directing its European team, but quickly became disillusioned with the project and dissolved his contract with Ball.

He's since re-retired and has battled a heart ailment, being implicated in Operacion Puerto and in legal troubles after splitting with his wife.

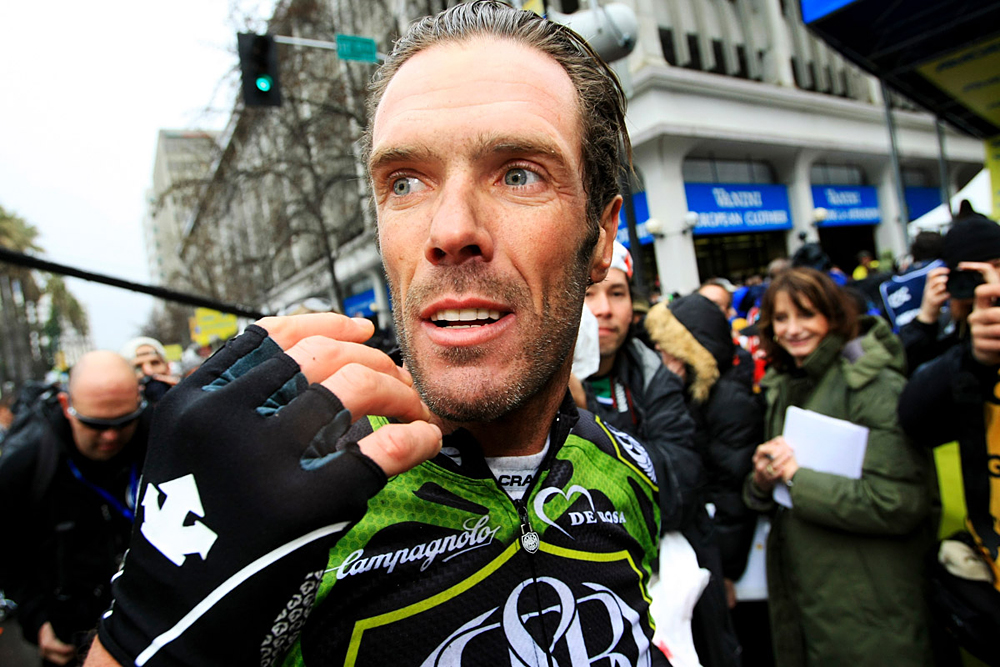

Michael Creed

Michael Creed spent two seasons in the sport's big leagues on the US Postal and Discovery Channel teams after becoming U23 national time trial champion.

He returned home in 2006 to race for Jonathan Vaughters' TIAA-CREF team. After the team went Pro Continental and became Team Slipstream with higher ambitions in 2007, Creed moved across to Rock Racing at the start of 2008.

Creed is now the director of the Aevolo U23 development team.

Tyler Hamilton

Tyler Hamilton established himself as a Grand Tour contender after coming out from the shadow of Lance Armstrong, having been a trusted domestique for the Texan's first three Tour de France victories.

He moved to Bjarne Riis' CSC team in 2002, and became famous for his grit and determination after pushing through the pain of a fractured shoulder to finish second at the 2002 Giro d'Italia, and then raced through a fractured collarbone at the 2003 Tour de France to win a stage and finish fourth overall.

He left Riis' outfit for the new Phonak squad in 2004, but again crashed in the Tour de France – only this time he dropped out. He went on to win the Olympic Games time trial in Athens. but during the subsequent Vuelta a España, he and teammate Santiago Perez tested positive for blood transfusions. Hamilton was banned through 2006 and named as a client of Fuentes in Operacion Puerto.

After coming back with the Tinkoff team in 2007 and then being dropped from its roster over the Operacion Puerto allegations, Hamilton jumped ship for Rock Racing, winning the US national championship in Greenville in 2008. He retired after testing positive in 2009 for DHEA, which he claimed to take for depression. He was subsequently banned for eight years.

In 2010, Hamilton became a pivotal witness in USADA's investigation into Armstrong and doping at US Postal, and in 2012 wrote a tell-all memoir with Daniel Coyle: The Secret Race: Inside the Hidden World of the Tour de France: Doping, Cover-ups, and Winning at All Costs.

He lives in Colorado and still runs a coaching business, and last year joined the investment advisers Black Swift Group to lead its Professional Athlete Wealth Advisory Division.

Victor Hugo Peña

Victor Hugo Peña came to the team after the failure of the Unibet squad to survive the UCI's squabble with the ASO, but he was a former lieutenant for Lance Armstrong during his reign at the Tour de France. Peña beat Armstrong by one second in the prologue of the 2003 Tour de France, and when it came to the stage 4 team time trial, the Colombian moved into the maillot jaune for three days – the first rider from the country to have led the Tour.

It was his last Tour with the US Postal team, and Peña left for Phonak along with Floyd Landis for two seasons before Landis' doping scandal spelled the end of that team.

In 2007, his Unibet team became embroiled in a spat between Tour organisers ASO regarding the number of ProTour teams. Unibet would have been granted automatic entry to the Tour, but the ASO tried to argue that sports betting and gambling advertising was restricted in France. They refused the team entry to the early season races and eventually the Tour de France, and the team disbanded.

Peña found a home at Rock Racing and won his last race with the team in 2009 at the Vuelta a Colombia. He closed out his final seasons with local teams and retired in 2015. He is now a stay-at-home dad.

Sterling Magnell

Sterling Magnell is currently the national team coach in Rwanda, having been brought over after retiring from racing at the suggestion of Tom Ritchey. You can read the full feature about Magnell here.

Doug Ollerenshaw

Doug Ollerenshaw came up through the collegiate-racing ranks, winning the Division 1 national title in 2003, then having a stint with Jelly Belly in 2004 and HealthNet for three seasons. He won a stage of Tour de Beauce in 2005 and a second place in the 2007 Tour de Georgia from a breakaway.

One of the smartest guys in professional cycling, Ollerenshaw retired after his year with Rock Racing in 2008 in order to pursue a PhD at Emory University in Georgia. He earned his degree in Biomedical Engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University in Atlanta, and is currently studying brain function with the Allen Brain Observatory.

Fred Rodriguez

Rodriguez came to Rock Racing after a successful European career with the likes of Mapei, Domo-Farm Frites, Acqua e Sapone and Lotto. A notable lead-out man and sprinter in his own right, Rodriguez finished on the podium of the 2002 Milan-San Remo and Gent-Wevelgem and won a stage in the 2004 Giro d'Italia.

Rodriguez also excelled on home soil, winning the national championship title in 2000, 2001, 2004 and late in his career in 2013.

He returned to the States to race with Rock Racing in 2008, landing on the podium in the Philadelphia International Classic in his first season and leading the team's European campaign in 2009.

When the team imploded at the start of the 2010 season after failing to earn a UCI licence, Rodriguez was left without a team. He signed in mid-2011 with Exergy – another flash in the pan project – before riding out his final three seasons with Jelly Belly.

He now runs a cycling clothing business in California.

Óscar Sevilla

Sevilla is still racing at age 43 with Team Medellin. After being blacklisted following Operacion Puerto, he spent a year with Relax-GAM before joining Rock Racing. He won a stage in the Vuelta a Colombia and the Reading Classic in 2008, and at the Vuelta a Chihuahua in 2009.

After being left team-less in 2010, he joined a team in Colombia but tested positive for Hydroxy Ethyl Starch. He served a year-long ban but during that time fell in love, got married and settled in Colombia and has continued his career at the Continental level, occasionally training with Egan Bernal.

He was crowned the winner of the 2018 Vuelta a San Juan Internacional after Gonzalo Najar tested positive and managed to finish third overall this year behind Remco Evenepoel and Filippo Ganna.

Justin Williams

Williams was fresh out of the junior ranks when he joined Rock Racing in 2008. He joined the nascent Trek-Livestrong team in 2010 but then stepped away from the sport to attend college.

His brother Cory convinced him to come back and now Williams is part of his own Legion cycling team that dominates the criterium circuit in Southern California.

Sergio Hernandez

Hernandez was just 22 when he signed with Rock Racing in 2007 and he remained with the team through to the end. A solid rider, he fought through injuries, racing with Jelly Belly for two seasons and InCycle-Cannondale for a few more before finally giving up on pro cycling and opening a bike shop in Puerto Rico. We could not reach Hernandez for this story.

We could not reach Brock Curry or Peter Dawson for this story.

Laura Weislo has been with Cyclingnews since 2006 after making a switch from a career in science. As Managing Editor, she coordinates coverage for North American events and global news. As former elite-level road racer who dabbled in cyclo-cross and track, Laura has a passion for all three disciplines. When not working she likes to go camping and explore lesser traveled roads, paths and gravel tracks. Laura specialises in covering doping, anti-doping, UCI governance and performing data analysis.