What is the Puy de Dôme? Inside the legendary Tour de France climb

All you need to know about the historic Tour de France summit finish

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Puy de Dôme is simultaneously somehow a new and old legendary Tour de France. Its status was burnished decades ago, helped by battles between cycling champions, its difficulty, its impact on the sport’s race and its unique appearance.

This verdant, volcanic plug and its white observatory tower is visible on the horizon around the Auvergne and the city of Clermont-Ferrand below. When covered by cloud, it can appear to be floating in the sky.

When the 2023 Tour de France visits the Puy de Dôme for the finale of stage 9, it will be like greeting a long-lost friend. It has not been included in the race since 1988, when Dane Johnny Weltz was the stage winner.

Its presence in the race will provoke a twinkle in the eye of those who can recall the great battles of yesteryear. This climb from a bygone era of toe clips and wool jerseys is back for a showdown.

On this Massif Central ascent, characterised by its green and gruelling final four kilometres, legends showed their greatness.

The Puy de Dôme made its debut in the race in 1952 when Fausto Coppi was victorious on the way to a dominant Tour de France victory.

Eventual race winner Federico Bahamontes made up most of his deficit with an emphatic time-trial win there in 1959. However, the climb is still associated with Jacques Anquetil, Raymond Poulidor and the electrifying duel the pair fought up the climb 48 hours before the end of the 1964 Tour de France.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

As the kilometres ticked by slowly, they rode together side-by-side and neck-and-neck, with the rock wall to their right. Neither gave in or pulled away. At last, bent over the bike and grinding slowly in the saddle, yellow jersey-clad Anquetil dropped back in the final kilometre.

The battle was lost, but he kept the race lead by 14 seconds and his fifth and final Tour win would be won. A nation was captivated and the Puy de Dôme’s place in cycling folklore was assured. Fittingly, the 182.4km ninth stage of the 2023 Tour de France which finishes there will start in Poulidor’s home of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat.

Regularly appearing in the final week of the Tour de France over the next 25 years, the Puy de Dôme could both decide the race’s kings and contribute to dramatic dethronings.

In 1975, Eddy Merckx was punched in the kidneys by a spectator close to the finish, an incident which contributed to his toppling by Bernard Thévenet two days later. It would be the last time Merckx ever wore the Tour’s yellow jersey in competition.

Eleven years later, Greg LeMond made good his advantage over Bernard Hinault, putting almost a minute into his La Vie Claire teammate to win the 1986 Tour.

Following its appearance in 1988, it was increasingly thought that a finish on the Puy de Dôme would be logistically impossible. The Tour appeared to have outgrown the mid-France climb, given the size of its organisation and commercial caravan. The train line built to the top in 2012 also narrowed the road even further. (The tarmac is not for public use, save for emergencies and services. However, one day a year, it is open to cyclo-tourists to ride up and test their mettle.)

However, the dream to include this evocative mountain in the modern Tour has been there for decades. “When I started at ASO in January 2004, the first thing I typed on my computer was: objective, Puy de Dôme. For me, it’s one of the strongest symbols of the Tour de France’s legend,” race director Christian Prudhomme told AFP.

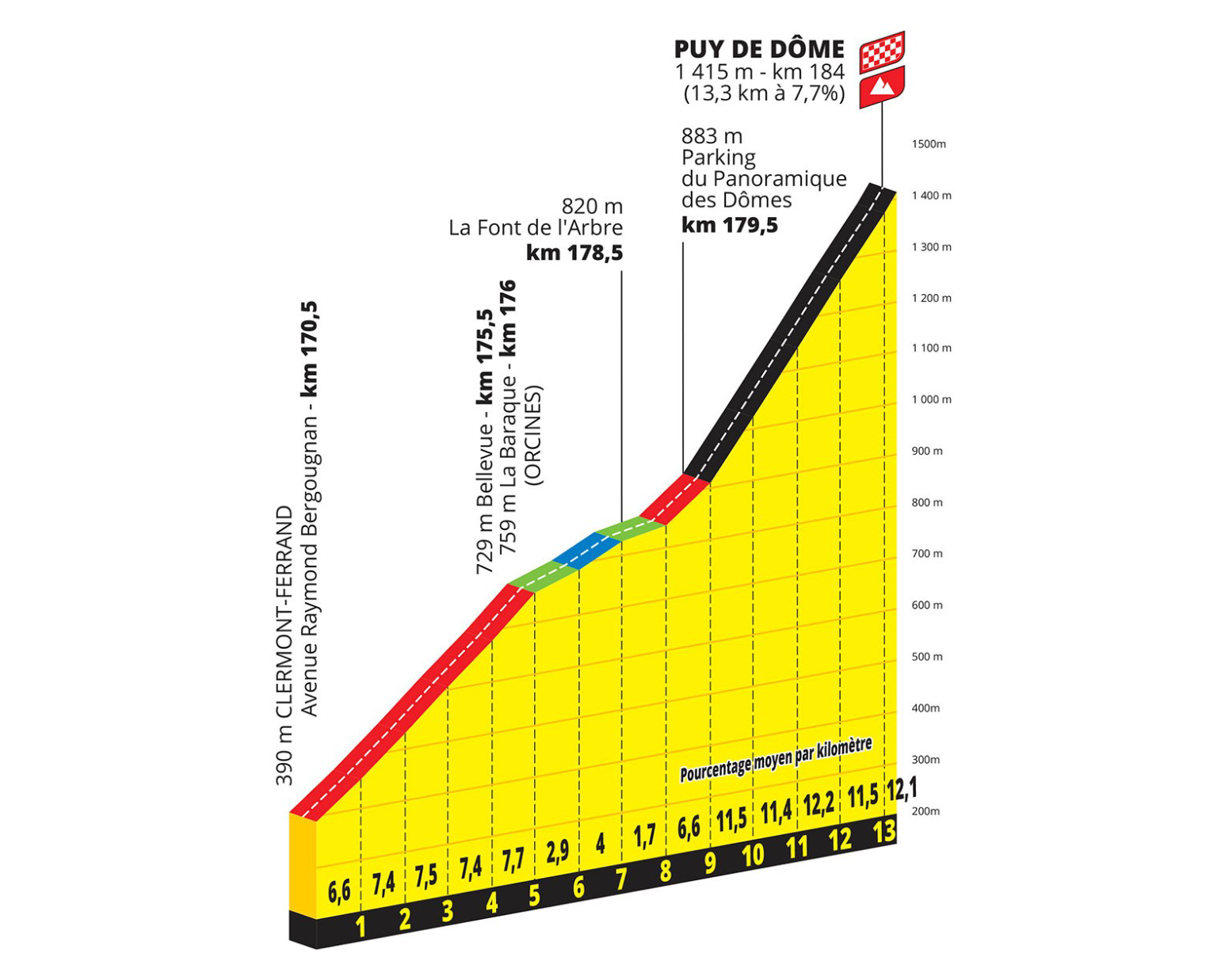

The 13.3-kilometre climb averages 7.7 percent gradient, but it has three distinct, different sections. The opening third, rising west from the outskirts of Clermont-Ferrand, averages approximately seven per cent before a gentler few kilometres of borderline false flat allow a slight breather.

From the Parking du Panoramique du Dôme, there’s no hiding. The road carries on to the finish for 4 kilometres at over 11 percent gradient. As the road curls round the volcano like a snail shell, some riders will feel like they’re inching along as slowly as that little mollusc. It cannot fail to break up the race and have an impact.

We tend to think of mountains like versions drawn by children: rocky expanses with elaborate hairpin bends and jagged, snow-capped tops. Not the Puy de Dôme, which tops out at 1,415 metres and has greenery as far as the eye can see. The views west over other summits in the Parc naturel régional des Volcans d’Auvergne are extensive.

There are no corners on the narrow road up, which hugs the volcano, climbing up next to the rail line which takes visitors to the top on a panoramic train. That will add psychological pain to go with the physical suffering for racers, who will have to judge their effort adroitly. Even on the last leg-hurting ramp of 18 per cent, the finish hides tantalisingly from sight.

“It’s very, very steep. I don’t think I’ve ever been up a climb like this. There is no respite. Without any corners, you have to keep the power on the pedals endlessly,” Jonas Vingegaard said after a reconnaissance ride.

The Puy de Dôme will also stand out for the silence and emptiness in its last part. It is just one of 80 volcanoes in the Chaîne des Puys, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Accordingly, there will be no spectators allowed in the final four kilometres to help preserve its flora and fauna.

Heat-seeking drones will even be in the skies in the days before the race’s arrival, seeking out any bold campers trying to hide in the undergrowth. During stage nine of the 2023 Tour de France, a minimal number of race vehicles will be permitted to follow the peloton, given the narrow width of the road.

Around the world, millions in a whole new generation will tune in to savour the return of the Puy de Dôme to the Tour de France. It’s down to the likes of Tadej Pogačar, Jonas Vingegaard and local hero Romain Bardet to be the authors of new myths and legends. Many will no doubt hope to see this brutal and beautiful climb in a top bike race again very soon.

Formerly the editor of Rouleur magazine, Andy McGrath is a freelance journalist and the author of God Is Dead: The Rise and Fall of Frank Vandenbroucke, Cycling’s Great Wasted Talent and Tadej Pogačar: Unstoppable.