What is the Côte de la Redoute? Inside the decisive climb of Liège-Bastogne-Liège

All you need to know about the pivotal hill of cycling’s oldest Monument

“The Côte de la Redoute is a Monument within a Monument” is how Liège-Bastogne-Liège director Christian Prudhomme recently described the race's most famous climb. La Redoute is not the steepest nor the longest of the ten to a dozen ascents included in each edition of La Doyenne but remains the focal point of the final Spring Classic of each season.

Although it was first climbed in the 1975 edition of a race which started in 1892 a sign stone the summit of the Côte de la Redoute says, “Here the greatest riders have forged their victories.”

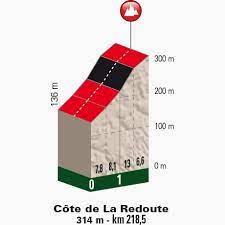

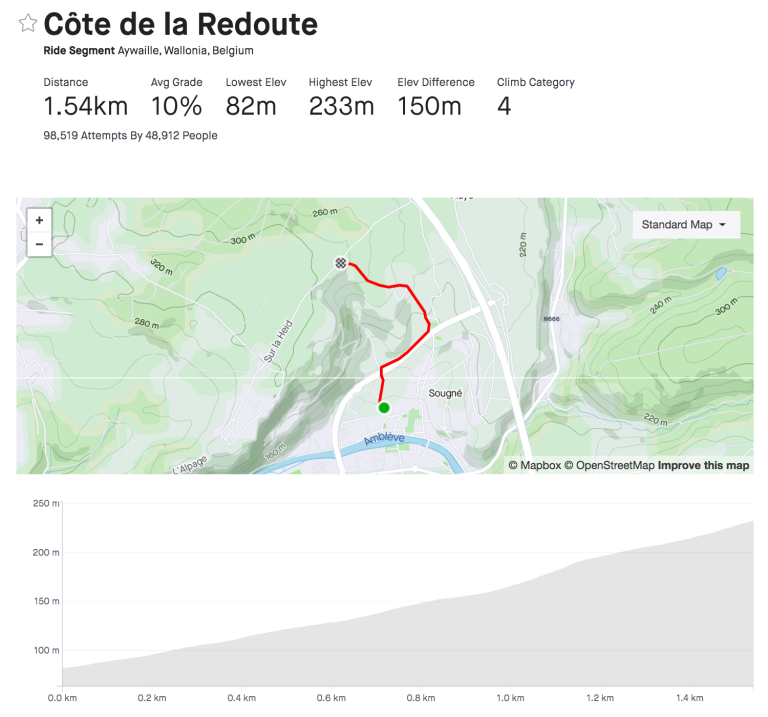

La Redoute is not the hardest climb of Liège-Bastogne-Liège. An average gradient of a leg-burning 9.4% for 1.6 kilometres puts La Redoute behind two other frequently used Liège climbs in difficulty: the Stockeu (1 km at 12%) and the Côte de la Roche-aux-Faucons (1.3 km at 11%).

The more recently created Liège-Bastogne-Liège Femmes, now in its seventh edition, always uses this emblematic climb, and it plays a similar pivotal role as in the men's race. La Redoute also features in the Under-23 men's version of Liège, and puts in occasional appearances in the Tour de Wallonie, the region's leading stage race.

What makes La Redoute so important, compared to the two harder climbs, is its position in the race. The Stockeu always forms part of an early trio of ascents (Wanne - Stockeu - Haut-Levée) tackled in rapid succession and which combine to lift the curtain on the crucial last 80 kilometres of Liège. As for the recently introduced Roche-aux-Faucons, it provides one last opportunity for the climbers to blast away on their favoured terrain before the definitive drop back to Liège.

La Redoute, on the other hand, set midway between prelude and final conclusion, is like the main act of a play. It won't tell us who’ll be lighting up cigars and knocking back the champagne in the five-star hotel in the last scene and who’ll be down on their luck and out on the street. But La Redoute pinpoints who the main actors of the afternoon’s entertainment in Liège will be, and what kind of plans (then mislaid or not) they have for their future.

Where La Redoute best played out that role as the main scene-setter was unquestionably the 1999 edition of Liège-Bastogne-Liège. In what was arguably the hugely controversial Belgian champion Frank Vandenbroucke’s finest racing moment, he and Italian Classics rival Michele Bartoli went toe to toe, a couple of metres apart but never so much as glancing at the other, nearly all the way to the summit.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Vandenbroucke briefly distanced Bartoli at the summit before easing back, then making a definitive attack in the Côte de Saint-Nicolas further on. But the tension of the two riders on La Redoute and then Vandenbroucke briefly edging clear remain some of the most memorable moments in the sport.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as double Liège winner Sean Kelly has pointed out on a number of occasions, La Redoute used to be the last big climb before the finish. As a result, if a breakaway escaped it was very hard to pull them back on the fast run-in.

The last part of the Liège-Bastogne-Liège route changed in the early 1990s, and the uphill finish at Ans and the last climb of the Côte de Saint-Nicolas rendered the Côte de la Redoute less relevant.

However, the return to the flat city centre finish on the Boulevard de la Sauvenière in 2019 has once again given the earlier climbs more prominence - and the Côte de la Redoute is, once again, back to being Liège's first climb among equals.

Since 2019, only one breakaway has formed on La Redoute and stayed away to the finish and it was a cracker. In 2022, Remco Evenepoel made a devastating attack on its highest slopes and soloed all the way to the line. It simultaneously marked a breakthrough moment for the young Belgian, saved the Classics team for his QuickStep team, and confirmed La Redoute’s revived status.

Geographically, the Côte de la Redoute marks the point where after 200 kilometres the Liège-Bastogne-Liège men's race leaves behind the bleak, wild beauty of the southern Ardennes, with its dense forests, isolated farmsteads and hauntingly empty, windswept plateaus. From La Redoute onwards, the Classic enters a patchwork of suburban semi-rural sprawl made up of orderly gardens and chalets, out-of-town supermarkets and petrol stations. This gives way in turn to a bizarre mix of university parklands and industrial wasteland that merge into southern Liège and the finish next to the River Meuse.

Starting off as an outlying village lane, the earliest part of La Redoute is anything but photogenic, running as it does out past a series of vegetable gardens, and through a short, echoing concrete underpass beneath an ‘A’ road. The next segment heading right and parallel to the same main road is hardly more visually interesting. But the lone line of fans' caravans lining one side and the banners popping up between them make a difference and the slope, wavering between 8% and 10% at this point, is already beginning to bite.

Once the route takes a 90-degree turn left, a point easily spotted as that's normally where the race barriers begin, the 'real' Côte de la Redoute begins.

The middle section is narrow, increasingly steep and agonisingly straight, its gradient digging into the hillside past country fields, with slopes running from 8% to nearly 16% at the end of a single 200-metre ramp. There are even some thankfully brief pitches of 22% on the left-hand bend where this ramp, the worst of them all, finishes.

The atmosphere is invariably electric. The crowds on each side are rarely less than five or six deep, the noise deafening. In the 2017 Worlds in Norway, for example, when Flemish rider Yves Lampaert wanted to say how noisy and fired up the Scandinavian crowds had been, he said “they sounded just like the crowds on La Redoute.”

Every metre or two there’s another sign painted into the road graffiti reading 'Phil'-'Phil'-'Phil' in honour of local hero Philippe Gilbert, the 2011 Liège-Bastogne-Liège winner who was born in Remouchamps, the town at its foot. When it comes to the final 300 metres, the crowds thin out and the gradient drops away from 16 to two percent as it joins another farm track.

But then there’s a short, slightly tougher segment of 6% between two gentle gradients - and with narrow, twisting roads across a high plateau that follows that is often seen as the best place to attack: that's what Remco Evenepoel thought in 2022.

In an intriguing change, the 2023 race will not reach the usual highest point on the Côte de la Redoute. Instead it will deviate off towards a new small climb, the Côte de Cornemont, before heading onto the more frequently used Côte des Forges.

It’s ironic that an ascent as renowned as La Redoute did not originally have a name of any kind. The climb was called that purely because its earliest part originally started in a back street of Remouchamps called Rue de la Redoute. That road up was blocked when the motorway and its access roads were built, but the name still stuck.

The word redoute is a military term for a kind of earthworks outside a fortress, in this case built on the hill about Remouchamps during the build-up to a major battle in the French Revolutionary Wars of the 1790s. But regardless of its unnamed past, when it comes to its role in the sporting present and future, La Redoute remains pivotal and a name everybody in professional cycling cannot fail to know.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.