What are Continuous Glucose Monitors? Explaining their use, the ban, and Faulkner's DSQ

We take a deep dive into the key question marks surrounding the small disc at the centre of a storm

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

During her long-range solo breakaway in the latter part of Strade Bianche, Kristen Faulkner was spotted by television cameras with a disc-shaped object on her upper arm. She later admitted it was a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), a device that was banned for use in competition by the UCI in 2021, and, despite her protests, she was stripped of her third place finish.

The rule she broke - specifically point three of article 1.3.006 BIS within the UCI's Technical Regulations - states that 'devices which capture other physiological data, including any metabolic values such as but not limited to glucose or lactate, are not authorised in competition.'

In the days following her punishment, Faulkner issued a statement, in which she reiterated earlier claims that no data was transmitted "during or after the race".

A separate statement was also issued by Supersapiens, the brand that provides its continuous glucose monitors to Faulkner and much of the professional peloton, stating this is an opportunity to better understand "why athletes are choosing to use CGMs".

However, a few questions remain, predominantly centring around the word 'why'. Why was Faulkner using one in the first place? Why didn't she remove it? Why do teams use them at all? And why are they banned?

To begin answering these whys, let's first look at a 'how'. Specifically, how the Supersapiens continuous glucose monitors work.

How do continuous glucose monitors work?

There are a few makers of continuous glucose monitors in existence, but the one most specifically aimed at sporting performance – and the one used by Faulkner – comes from the American brand Supersapiens.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The Supersapiens product leverages the tech within an Abbott continuous glucose monitor, which was originally created for diabetics.

To use it, you apply the monitor to your upper arm using an applicator. This uses a needle to penetrate the skin, opening a hole through which a hair-thick filament is pushed. The needle then retracts into the applicator, leaving the filament in place. At the base of the filament is a plastic disc-shaped patch, which houses all of the circuitry, battery, NFC chip, Bluetooth chip, onboard memory and so on. This sticks to your skin holding the filament in place.

For context, this writer has tried it. It's mostly painless, but Southerland has previously said it's possible to catch a nerve, which can be "uncomfortable" for a couple of days.

Once applied, the sensor needs to be 'activated' within the app. Once activated, each sensor is valid for two weeks - presumably due to battery life or hygiene reasons - before it will lock itself. Prior to activation, and indeed at the end of the two weeks, the sensor is essentially asleep, for want of a better word; it's little more than jewellery. It will not collect data even if it has been applied to your arm.

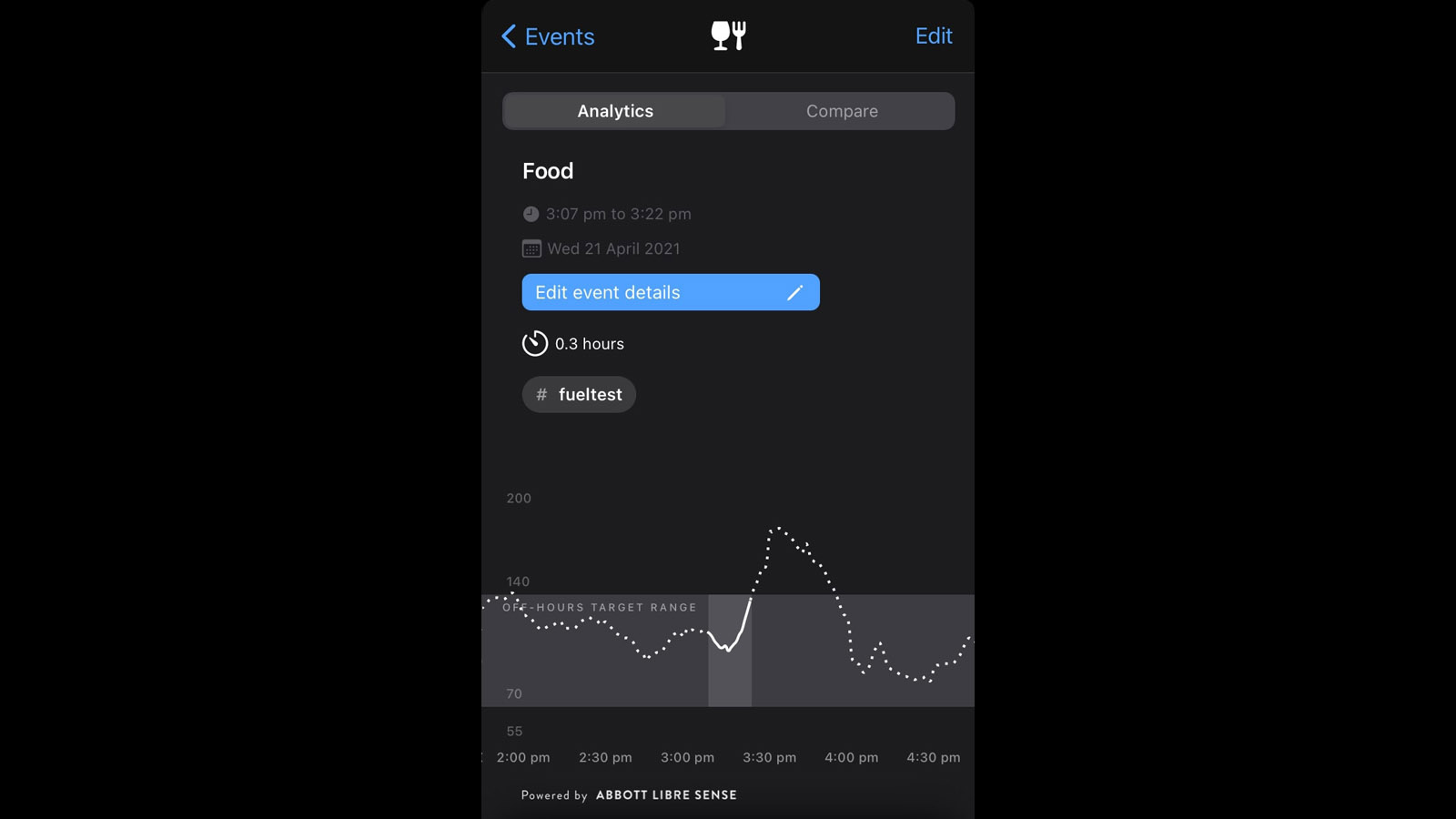

Importantly, within that two-week 'awake' period, the continuous glucose monitor will continually collect data from the filament sensor in your arm. What it does with that data is dependent on whether it's currently connected to a smartphone or bike computer.

If it's not connected to any external device, it will store the data it captures on its onboard memory, where there is approximately enough memory for eight hours of data. The user can then use the onboard NFC chip to transfer this data to a smartphone later. If the monitor is connected to a third-party device, such as your smartphone or a cycling computer, then it will transmit the data in almost real-time (it can have a delay of up to 15 minutes) to said device.

Faulkner's case

In Faulkner's statement, she says: "No race data was ever transmitted during or after the race. I was under the impression that I could race with my device if it did not record any data, because there was no performance advantage whatsoever. The UCI holds the position that wearing a non-connected patch itself – even if there is no transmission of data and no performance advantage – is enough to disqualify me."

Notably, Jayco-AlUla's bike computers are branded as Giant and supplied by Stages. Even if Faulkner was trying to get real-time glucose data, there is no integration between Stages and Supersapiens, so it would have been impossible. Of course, that doesn't totally disprove the possibility that it was collecting and storing data for later analysis.

Based on Faulkner's statement, it would appear that she 'applied' the sensor, but had not yet 'activated' it within the app. As unusual as this may be to an average user, it's entirely possible that Faulkner got the call-up moments after applying the sensor, before she had the chance to activate it.

"I was a last-minute reserve for Strade, so I didn’t know I was racing when I put it in," Faulkner stated on Twitter. "In my attempt to clarify the rules, I asked a trusted staff member on my team before the race If I could wear it. They said yes, because I couldn’t see any data. I was not the only person confused about the rule."

Unfortunately for her, however, the wording of the UCI rule centres around the use of the device that captures data, not specifically the capture of data itself.

Why might Faulkner keep it on, knowing the rules?

Many will argue that Faulkner should have just removed the device in order to avoid the risk. Her reasoning here, beyond the confusion, is two-fold.

Firstly, continuous glucose monitors are expensive. Once applied, sensors cannot be removed and reapplied, and they cost €75 each. Given that Supersapiens has previously offered to supply the entire peloton with devices free of charge, it's unlikely to have been the primary factor in Faulkner's immediate decision, but regardless, wasting a sponsor's product is perhaps a cost that Faulkner wanted to avoid.

Secondly, and arguably more importantly, is that this was the last one she had. "[They're] difficult to ship from the USA to Spain. I only had one left and I didn’t want to waste any," she explained in a separate tweet.

Poignantly, in a response to another tweet, Faulkner said: "Men don’t lose their periods and become infertile due to under-fuelling," which leads us to the motivations for using a CGM in the first place.

Why do pros use them at all?

Continuous glucose monitors were originally designed for use by diabetics, for whom excessively low blood sugar can be life-threatening. Supersapiens' founder Phil Southerland, a diabetic himself, used various iterations of glucose monitoring technology in his own sporting career, finding that when monitoring his glucose closely, he could perform just like any other athlete. He later integrated the CGM technology into his work with Team Type 2, a pro team made up of diabetic cyclists that's now known as Team Novo Nordisk.

Given that glucose is - simply put - fuel for our muscles, Southerland noticed an opportunity to leverage the data to aid athletic performance for non-diabetics too.

For professionals, by monitoring the effect of diet on glucose levels, coaches and athletes can optimise nutrition strategies to ensure glucose levels are at a constant optimal. Done correctly, performance improvements should follow thanks to better adherence to workouts, faster recovery, and more.

Long-term under-fuelling is a problem affecting both men and women cyclists, especially at the upper echelons of our sport where weight is so closely tied with performance, oftentimes inaccurately so. But women are particularly susceptible, with the loss of periods among the various symptoms of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S).

Of course, a CGM device is simply a tool, like a power meter or a heart rate monitor. It's not the entire picture, but it provides another piece to the puzzle that is the picture of an athlete's health and performance.

The benefit of wearing one in a race

Were it legal, having real-time glucose data in a race could give a rider an idea as to how well-fuelled they are going into an important part of a race.

Seeing a low glucose level on their bike computer would perhaps inform a rider not to take on a high-effort long-range attack (during which glucose would be needed as the primary fuel source), and would be a reason to eat more. Conversely, seeing constant levels throughout the race might inform the rider they are successfully adhering to a pre-planned nutrition strategy.

There would also be value for post-ride analysis. Perhaps if a rider tried that long-range attack but blew up before the finish, then coaches could understand whether it was due to a lack of fuel or something else.

Why are they banned?

We've seen the rule, but the 'why' is the difficult question here. At the time of the announcement that the monitors would be banned, EF Education-EasyPost's CEO, Jonathan Vaughters, quipped that it was "On brand" from the UCI saying: "If they can’t understan' it, they ban it."

The governing body's innovations manager, Mick Rogers has since offered some arguments, including concerns over personal privacy, financial accessibility and, most importantly, the increasing influence of technology on human racing.

"The fans don't want to see Formula One in bike racing, they want surprises, they want unpredictability," Rogers told Cycling Weekly. "We feel that putting such powerful information into the hands of younger riders is taking away a skill - deciding when you need to eat and learning about your body [...] It shouldn’t be a completely automated process where every decision is being taken by technology."

Meanwhile, Southerland said that he didn't want his product to be an advantage for one team over another, and that the company would be happy to supply them free of charge to all teams. To our knowledge, this didn't happen officially, but there aren't many WorldTour teams not using the technology in training these days. Alas, it didn't affect the rules, and they remain banned.

Should Faulkner have been punished?

According to the letter of the law, yes. As mentioned above, the the wording of the UCI regulations means that simply by wearing the device - whether or not it was transmitting data - Faulkner broke the rule in question.

The UCI also states in relation to Article 1.3.006 BIS: 'Derogation requests shall be assessed, inter alia, in consideration of criteria of equal access to equipment, sporting fairness and integrity, and shall also comply with articles 1.3.001 to 1.3.006. Derogations may be limited to specific events and riders or teams.'

This is understood to relate primarily to riders with diabetes, who are permitted to wear CGMs in competition. Faulkner did not submit a prior application for derogation and the evidence she submitted to the UCI was clearly not enough to get her off the hook.

Of course, we've not seen the evidence that Faulkner presented to the UCI, so we cannot say for sure, but if as we suspect, the device had been applied but not activated, then from a performance advantage standpoint, it's no different to carrying it in your pocket. That brings us back round to the question of whether the rule - even if correctly applied - is fit for purpose.

Supersapiens statement

Notably, within Supersapiens' latest statement in response to Faulkner's punishment, it has requested that the UCI "start to see CGMs and Supersapiens as a tool for athletes to protect their bodies, not as some sort of performance enhancement device. This isn't about going faster. This is about health.

"We understand nutrition has a much bigger impact on an athlete than just results. As such, Supersapiens has been funding, supporting, and driving female-specific research into the association between menstrual cycle phases and glucose levels in elite female endurance athletes.

"Supersapiens invites the UCI to collaborate around collectively establishing data sets and continued scientific learnings with the goal of designing science-based best practices for optimising nutrition and recovery and mitigating eating disorders."

This ties neatly back to the discussion around RED-S and Faulkner's motivations for using the device in the first place, which is an important topic, but one that deserves its own feature.

Josh is Associate Editor of Cyclingnews – leading our content on the best bikes, kit and the latest breaking tech stories from the pro peloton. He has been with us since the summer of 2019 and throughout that time he's covered everything from buyer's guides and deals to the latest tech news and reviews.

On the bike, Josh has been riding and racing for over 15 years. He started out racing cross country in his teens back when 26-inch wheels and triple chainsets were still mainstream, but he found favour in road racing in his early 20s, racing at a local and national level for Somerset-based Team Tor 2000. These days he rides indoors for convenience and fitness, and outdoors for fun on road, gravel, 'cross and cross-country bikes, the latter usually with his two dogs in tow.