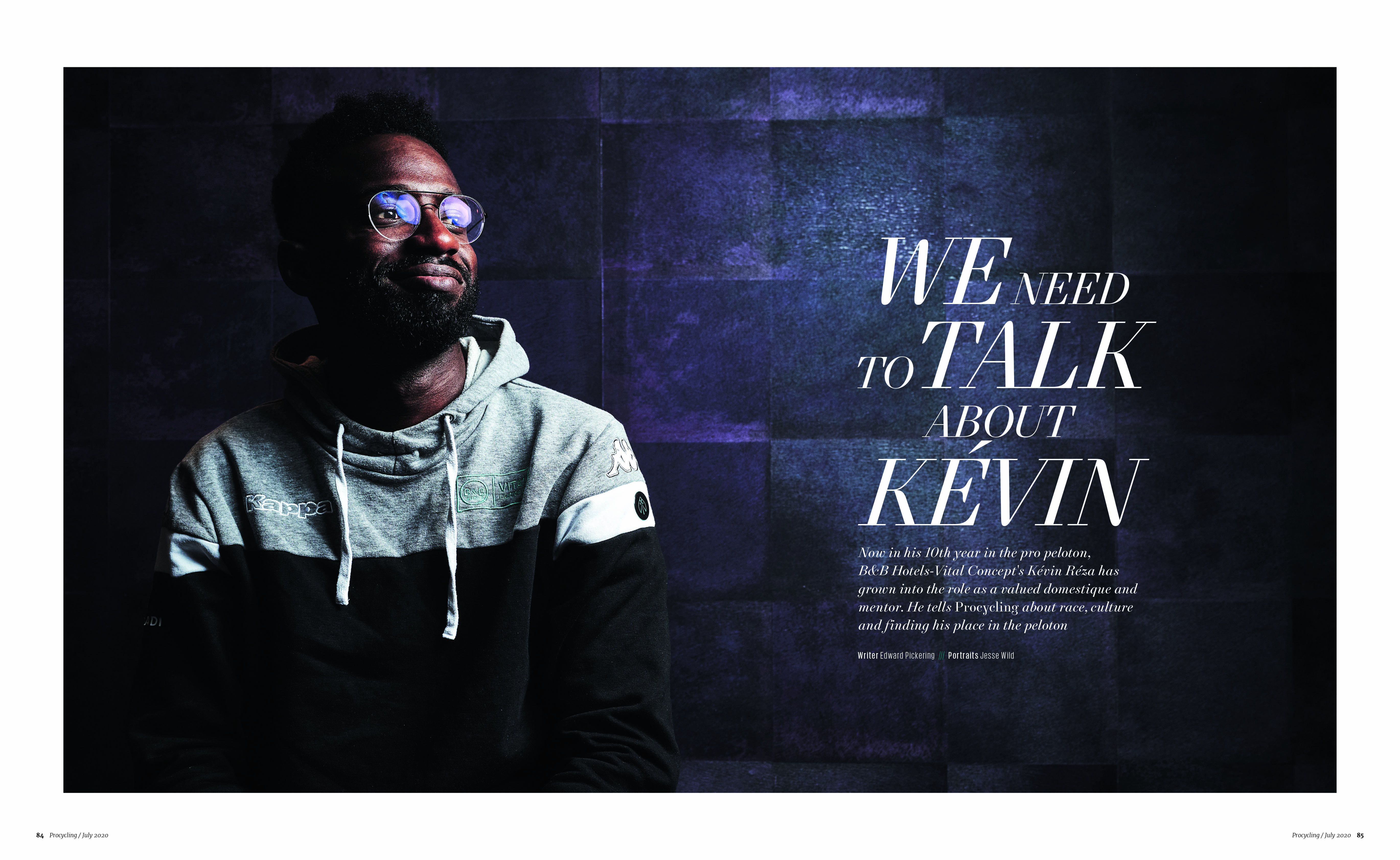

We need to talk about Kévin

Last month, we published an extract from Procycling magazine, but here you can now read the full interview with B&B Hotels-Vital Concept's Kévin Réza

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world’s toughest sport. Pick up your copy now in all good newsagents and supermarkets, or get a Procycling print or digital subscription, and never miss an issue.

This article is from the July 2020 edition of Procycling

The podium of the French National Championships in 2014 said a lot about France, about cycling, and about the politics of both these worlds. On the top step: Arnaud Démare, the sprinter for the FDJ team. The runner-up was also a sprinter for FDJ: Nacer Bouhanni. Europcar's Kévin Réza had come third.

In the enclosed world of cycling, eyebrows were mainly raised at the intra-team politics of the top two riders. Everybody knew there was no love lost between Démare and Bouhanni, uneasy cohabitants in the same team; Bouhanni is an open book, and so the disappointment was visible on his face. But the podium also spoke of wider issues. It reflected perfectly the culture of contemporary France – a 'black-blanc-beur' podium that represented the 'black-white-arab' make-up of the French population and reflected a lot of the commentary on the French football team. And if there was tension between Démare and Bouhanni, well, didn't that also represent reality to an extent, uncomfortable as it might be for any idealists who might have wanted to use it as a symbol of unity and harmony?

From Réza’s perspective, happiness at the sporting achievement was the primary emotion.

"The podium represented modern France and I was proud to be there," he tells Procycling.

His parents, who had come to watch the race, had heard comments in the crowd, but they ignored them.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"They had the intelligence not to answer. That kind of reaction is stupid," he says.

Even in 2020, Kévin Réza is unusual in the peloton. His parents grew up in Guadeloupe, a French territory in the Caribbean. He was born and grew up in the southwestern suburbs of Paris, then moved in his mid-teens to attend a sports school in La Roche-sur-Yon in the Vendée. He still lives in the Vendée, although he describes himself as an eclectic mix of his roots – a city boy who lives in the countryside and escapes to Guadeloupe at least once a year.

"They're very different places, but I feel at home in all of them," he says.

"Guadeloupe is exotic, and I like to go there after the season. The season is always very stressful. So after months of competition, I need to recharge my batteries, and I know that Guadeloupe is good for that, and really good for me. Everything is more relaxed and it lets me get things in order. That's the cool side. The zen.

"Paris is home, I have my family and friends there, and I'm a city boy at heart. And in the Vendée, I have my professional life and am still near the sea and sun."

Réza has full ownership of his culture and background, and he says he always has done. However, it's been a longer journey to find his place within cycling, and he's still looking, to an extent.

He's a decent sprinter, although his best performances have been as a lead-out man for Démare when he rode for FDJ, for Bryan Coquard first at Europcar and now at B&B Hotels-Vital Concept. He's growing into the role of team mentor.

"The most simple way to put it is that I'm here to motivate the guys not to have negative thoughts, to always be positive and help the younger riders bring out their talent, because it is there," he says.

"I can show them the right path to take, having learned from my own experiences. When I started at Europcar, the older riders taught me a lot, and now I can transmit that to the next generation."

Initially, Réza found the responsibility of a mentor hard to deal with. He admits that he's an introvert, who sometimes hides his shyness with jokes, but his B&B Hotels team manager Jérôme Pineau had more confidence in him than the rider himself.

"Jérôme talked to me about the role, and the first months weren't easy, but I've grown into the responsibility," he says.

Réza is part of a silent majority in the peloton. He hasn't won a professional race yet, and he has learned to come to terms with the hard reality that when your job is to support other riders, it's almost impossible to win. But at the same time, one of the things that drew him into cycling was the competition. This tension is ever present in cycling.

"I know I haven't won a race," he says. "I'm a competitor. We race to win. And I've had good results in races, even at the Tour de France. But I still haven't had the chance to raise my arms in a race.

"I fell into the role of pilot fish, so my job is to help my teammates win, or try to win. I've celebrated a lot of wins by proxy, and that is almost the same.

"I'm proud of what I've been able to do. But, at the end of the day, I'd like to have that feeling of winning. There is still hope," he says.

But ironically, success came to him earlier than it does for most. He was encouraged into the sport by his cycling-mad father. The young Kévin didn't need to be pushed, however – he wanted to copy his older brother, four years his senior, who was also riding, and he started riding at the age of four, and racing at the age of six. The family joined CSM Puteaux, a sports club in Nanterre, Paris, and Kévin was in his element.

"It was pure pleasure. There was no ego involved," he says. "We trained on a Wednesday evening and rode on Sunday mornings. Sometimes we raced on a Sunday and then we'd have a barbecue with the other club members.

"My friends were all into football, so being a cyclist was already a little different. But I had good teachers, and they taught us how to love the bike."

Although winning hasn't come easily to Réza the adult, he had a lot of early success. He was the national champion two years running, at six and seven years old.

"I started winning early," he says. "I was French champion two times at that age, and I still have the piss taken out of me by my teammates about it now. But a win is a win. It's part of my history, and being national champion was great. I still have the tricolour jerseys."

Turning professional wasn't necessarily Réza's destiny, however. The early success wasn't followed by a clear trajectory towards a career in the sport, and he struggled through his junior years, both at school and in sport. He admits that he was having a hard time academically, and proposed to his parents that he apply to sports school.

He failed the entrance exam for one in Roubaix, but got a spot in Notre-Dame du Roc, a sports school in La Roche-sur-Yon, and at the age of 16, he left for the Vendée.

"I still wasn't thinking of turning pro at that point," he says. "I found it very difficult. There was a lot of competition, and I wasn't physically mature. I was a lot smaller and skinnier than the others. But I kept going, and getting beaten back, and then got better and better."

Finding a place

After he left school, Réza got a place on the Vendée-U under-23 squad, the feeder team for Bbox Bouygues Telecom (now Direct Energie), rode as a stagiaire for them, and finally signed for them in 2011 when they became Europcar.

"I've never been a fan, and it was never a dream to be a professional," he admits. "It was more about goals.

"As a stagiaire, things had gone well and I thought it would be easy to find my place among the pros. But it was difficult. The older riders, like Thomas Voeckler and Anthony Charteau, quickly made me understand, but my first year was very hard. I think my character didn't help – I'm not good at speaking my mind.

"I had difficult moments physically, but it was more of a mental challenge. I had to come down off my cloud, and learn what I had to do."

Once Réza settled, things improved. He rode his first Tour de France in 2013, achieving two top 10s, including on his 'home' stage on the Champs-Élysées, in between supporting team leader Voeckler. The following year, he established a good rapport with the team's sprinter, Bryan Coquard, developing into a lead-out rider. A breakdown in communication with his team led to his transfer to FDJ in 2015, where he was put in the service of Démare.

"I was a bit angry when I left Europcar," he says. "I hadn't wanted to leave. It was a good team for me. Then my first year with FDJ wasn't great – I wasn't feeling good in the races and I was having trouble communicating with my teammates and understanding what they wanted me to do. It was the same on their side, and it was a complicated season for me to manage. When you change teams, you try to please the new team, and gain their confidence. But the first months were not as I'd hoped and I think I withdrew, and went inside myself a little."

Réza's career was hit hard by a crash in the 2016 Vuelta a España, in which he fractured his skull. The rehabilitation and recovery was hard. Even harder than that was finding his confidence again when he returned to racing.

"It was complicated," he says. "I lost confidence and I was riding differently afterwards. I still got results, but I was a different rider. There were three fractures, so managing the recovery was hard, and I was still young at the time and found it difficult to talk about.

"I considered stopping, but I didn't want to stop with a failure. I didn't want to have done all that work for nothing. Psychologically I found it very difficult to be in a peloton again, especially when I was riding close to the others, or when things got sketchy.

"You can put it out of your head, you do what you have to do. You have to take risks, or you can't race, but even now, three-and-a-half years later, I still have a fear of falling. On the other hand, I do a lot of strength training that I didn't do before, so I actually feel physically stronger than before the crash."

Kévin Réza is now in his 10th season as a pro, and he thinks he's found his place.

"I remember, when I turned pro at 22, I always said, 'Don't worry, kid, you have plenty of time.'

"Here I am now and it's already been 10 years. It's passed very fast. But on reflection, you learn a lot in 10 years," he says. "If you have a career that is a decade long, it means you've had a good career. I'm satisfied to have toughed it out, that I've been able to survive."

This article is from the July 2020 edition of Procycling

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world's toughest sport. Pick up your copy now in all good newsagents and supermarkets, or get a Procycling print or digital subscription, and never miss an issue.

Follow @Procycling_mag on Twitter

Edward Pickering is Procycling magazine's editor. He graduated in French and Art History from Leeds University and spent three years teaching English in Japan before returning to do a postgraduate diploma in magazine journalism at Harlow College, Essex. He did a two-week internship at Cycling Weekly in late 2001 and didn't leave until 11 years later, by which time he was Cycle Sport magazine's deputy editor. After two years as a freelance writer, he joined Procycling as editor in 2015. He is the author of The Race Against Time, The Yellow Jersey Club and Ronde, and he spends his spare time running, playing the piano and playing taiko drums.