Waterproof fabrics explained: What are they and how do they work?

Membranes, DWR, hydrostatic head, 2-layer, 3-layer, what does it all mean?

Here at Cyclingnews, we’ve put a lot of effort into helping you stay warm and dry over the last few weeks. We’ve not only put together a guide to the best winter cycling jackets, but also a separate guide to the best waterproof cycling jackets too. However, especially when it comes to waterproof cycling jackets, there is a fair amount of jargon. As far as we’re concerned, forewarned is forearmed, and the more you know as a consumer about the tech behind your purchases the better. It’ll allow you to make better decisions and potentially save some money too by not buying something that you don’t need.

In this article, I’m going to attempt to demystify everything I can think of about waterproof jackets. We will go through how they work, both the waterproof membrane part and the water-repellent bit, as well as diving a little deeper into waterproof and breathability ratings before doing a run through the key players on the market so that you can look at that Gore-Tex Pro label and think “that’s not actually what I need”, before reaching for something more suitable.

There is a big shift coming in the outdoors industry, with global supply chains moving away from fluorinated carbon chemistry. What this means is that, in the long term at least, waterproof garments as we currently know them will have to change. They will have to move away from expanded polytetrafluoroethylene to other options, and the durable water repellent (DWR) coatings too will have to change chemically. The mechanics of how it all works though, so far as we can tell at the moment, will remain the same.

A short glossary of terms

Before we continue, and given the stated aim of this piece is to demystify, I thought it best to begin with a short glossary of the key terms.

Waterproof - In order to be called ‘waterproof’, the item in question must be able to withstand a column of water 1000mm high for 24hrs, but as we’ll get into, there is a broad range of performance beyond that.

Water resistant - This is basically everything that isn’t ‘waterproof’, and will usually take the form of a DWR-coated softshell. Still able to resist a shower, but not prolonged downpours.

Breathability - In its simplest form this is a measure of how sweaty a jacket will be once you start moving. It’s measured in terms of how much water vapour can pass through a set area of fabric in 24hrs. This is always measured in lab conditions though, and can be affected by various factors.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

DWR - Durable water repellent; a wonderful chemical coating on the outside of fabric-faced garments that is hydrophobic, causing water to bead up and run off. Can be applied to just about anything.

Gore-Tex - This is a brand name, produced by Gore Fabrics, and encompassing a wide family of waterproof and water-resistant fabrics. It is not quite synonymous with ‘waterproof jackets’ as Hoover is to vacuum cleaners, but it’s not far off. Just bear in mind that it represents several options in a market of many many more.

How does a waterproof membrane work?

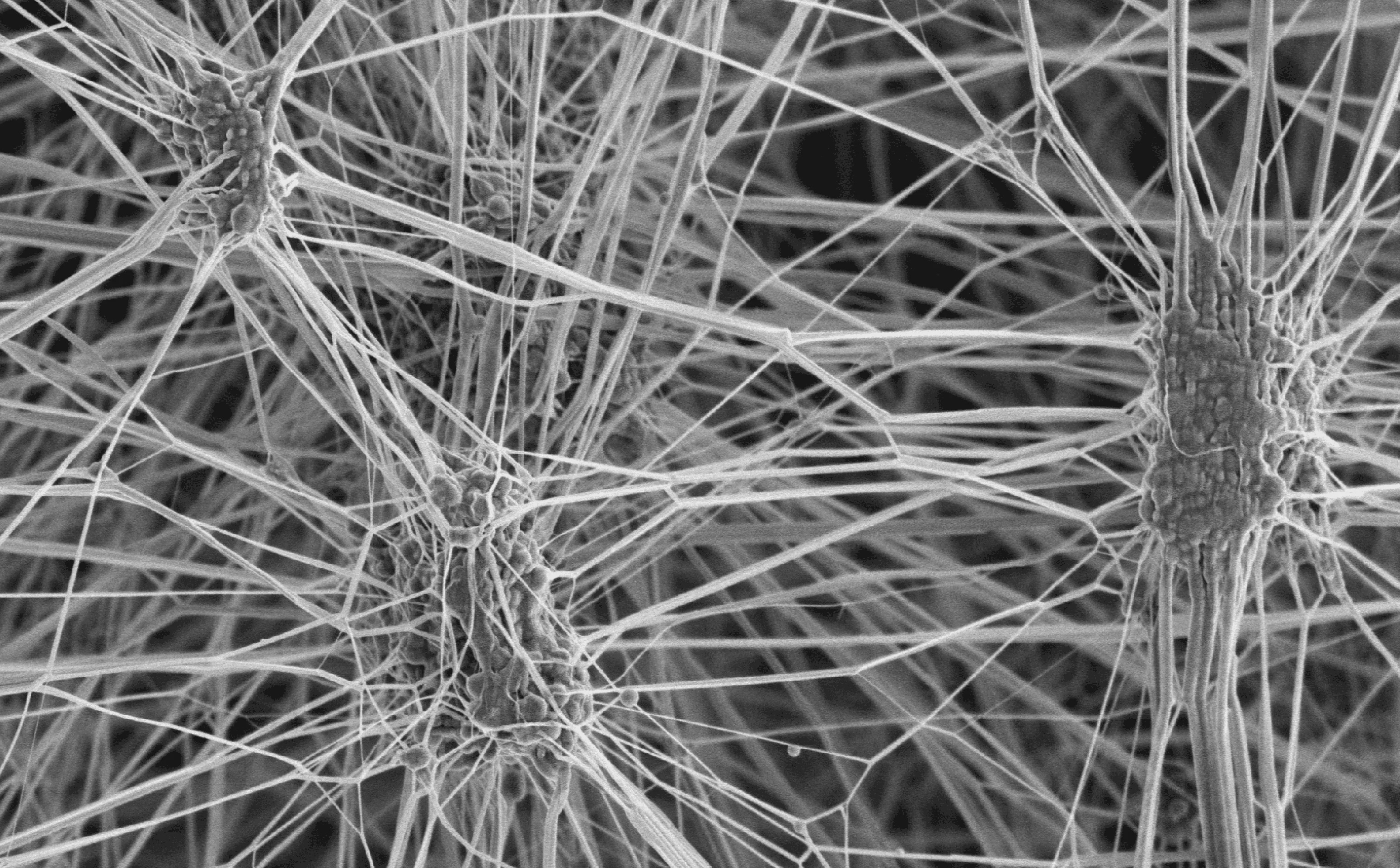

At the heart of nearly every waterproof jacket, or anything else waterproof for that matter (shoes, gloves, socks) there is a waterproof membrane. These are in most cases made of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE for short), with some options made of expanded polyethylete (ePE). The latter is going to become the norm in the not-so-distant future thanks to global supply chains beginning to turn away from fluorinated carbon chemistry; it’s nasty stuff for human health and the environment, but in the form of ePTFE it’s totally safe and inert, so no need to panic.

The first indicators of the shift that’s to come in the outdoors industry began with Gore Fabrics announcing that it’s to retire the high-performance Shakedry fabric. Beyond that we’re not sure what’s to come beside a likely shift to ePE membranes, but our product tester Josh Ross has spent some time digging and interviewing some big players in the waterproof game to work out where the industry goes next.

Regardless of whether it’s an ePTFE or an ePE membrane, the basic mechanism is the same. The way it was explained to me when I worked at an outdoor store was thus: To make ePTFE you take sheets of PTFE, which is exactly the same as what plumbers tape is made of, and you heat it and rapidly stretch it. This creates billions of tiny holes, which are the key to everything.

Water, in its liquid form, is bound by surface tension. The holes in the membrane are physically too small for water droplets to pass through unless they are forced to do so by pressure, which we’ll touch on later when we discuss waterproof ratings. However, and this is the real bit of magic, the holes are small enough for water in its gaseous state to pass through, meaning that as your sweat evaporates it can pass into the environment rather than condensing inside the jacket, leaving you soaking.

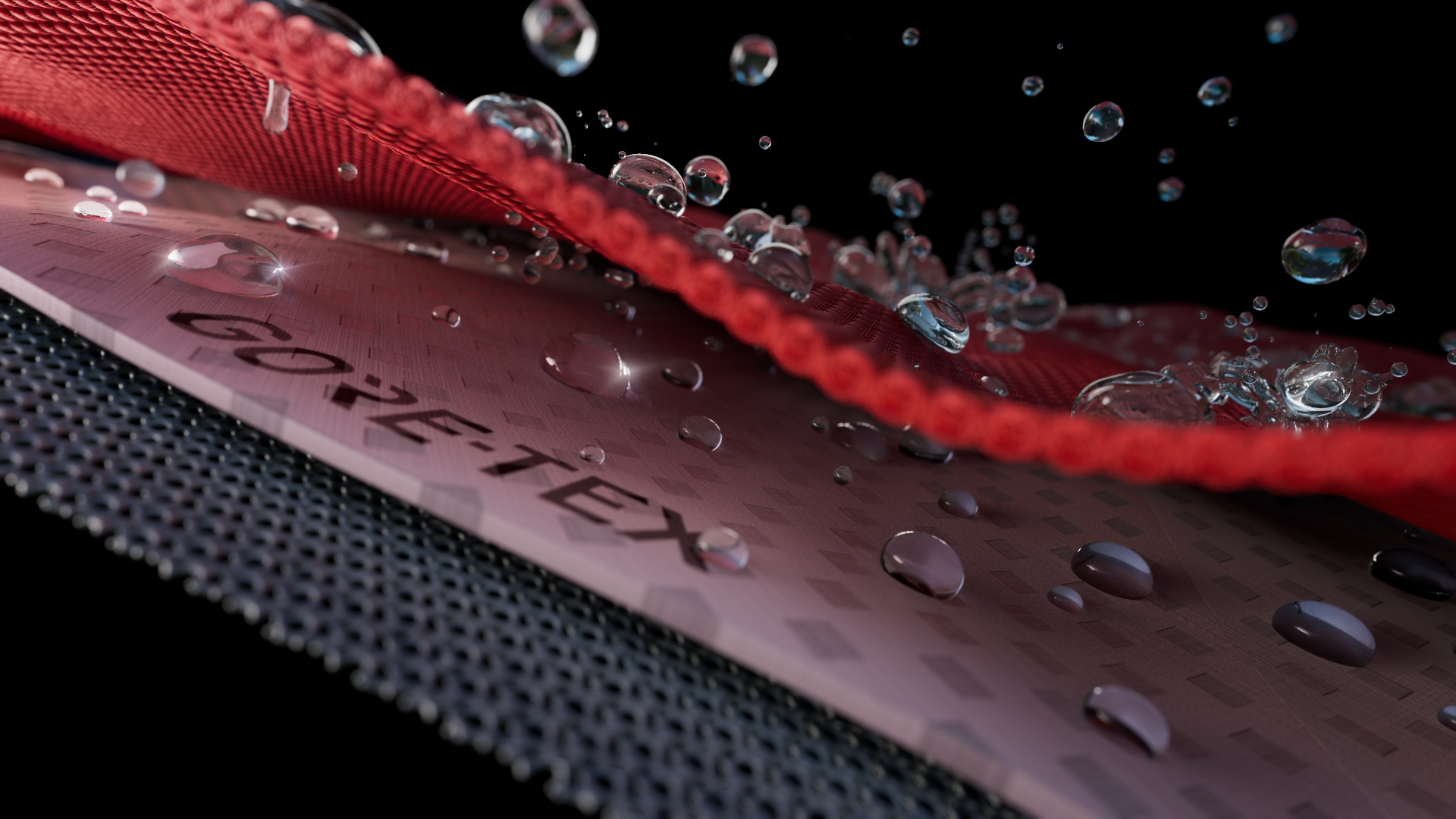

These membranes are fragile though, and if contaminated by dirt the pores can clog. In order to protect it, the membrane is sandwiched between other layers in varying combinations.

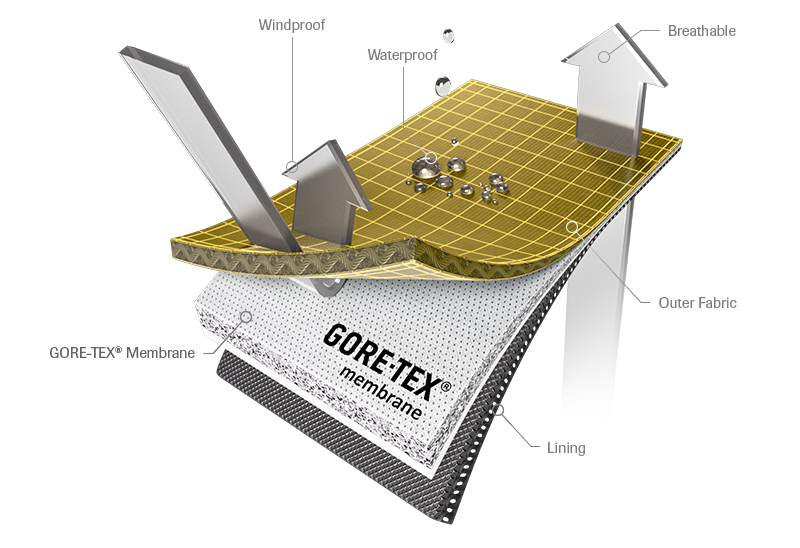

2 layer, 2.5 layer, or 3 layer?

In most cases, the waterproof membrane is bonded to a face fabric. This is what you see as the outside of the jacket, and manufacturers can make this as light and flexy or as heavyweight as they please, or mix and match in different areas to tailor (with heavier shoulders to resist backpack wear, for example).

Two-layer jackets call it a day at that, and simply suspend a mesh inside the jacket as a lining. Through this mesh you can usually see the white ePTFE membrane. Two-layer jackets usually represent the budget end of the jacket spectrum; they’re less packable and a bit heavier due to adding the mesh layer, and tend to use bulkier face fabrics.

Three-layer jackets on the other hand sit at the other end of the spectrum and occupy the more premium spaces. As well as an outer fabric, they have a protective inner layer bonded onto the membrane, which much better protects the membrane from the dirt and oils from both your body and the environment that can hamper its breathability over time.

Between the two, you’ll find 2.5-layer waterproofs. These take the form of an outer fabric, then a membrane, but instead of an inner fabric bonded on, or a mesh, these systems instead opt for a spray-on protective coating. They’re effectively just superlight three-layer jackets that aren’t quite so durable, but for cycling, they can make a lot of sense, especially if you’re not wearing a backpack or any other luggage.

Gore-Tex Shakedry, as is found on the Rapha Pro Team Lightweight Gore-Tex Shakedry Jacket, is something of an anomaly in that it is a two-layer fabric, but instead of featuring a membrane and an outer fabric, it places the membrane on the outside and just uses an inner lining fabric to protect it from your bodily excretions.

DWR and the importance of reproofing

However good a waterproof membrane is, if the outer fabric becomes saturated with water, there is no way for your sweat to escape, at which time you will get very soggy. This is usually the point where people assume that water has come through the jacket. Unless it’s burst through the seams or been forced through somehow this will almost certainly not be the case. This is where the durable water repellent comes in.

In short, the DWR is a chemical spray applied to the face fabric and it produces a hydrophobic effect, causing water to bead up and run off. The ‘durable’ nature of it is transient though, as with time or washing, the coating wears off and allows the face fabric to be more easily saturated. As such, it is important to reproof your jacket, or trouser, or anything else with what usually takes the form of either a spray-on coating or a wash-in treatment.

For best reproofing results though you should wash your garment first too. As the tiny pores in the membrane clog up this also reduces the breathability, and washing flushes these out and restores the ability to breathe. It is important to wash waterproof garments absolutely according to the instructions and only with approved chemicals; normal washing detergent can deteriorate the membrane and with it any usability of the garment for the purpose it was intended.

With non-membrane, water-resistant garments (softshells, basically, like the Gabba) you can be a bit more cavalier with your washing, but still follow the instructions. Fortunately for you, we have a separate explainer of hardshell vs softshell jackets if you wish to go down that particular rabbit hole.

Waterproof and breathability ratings

As I alluded to in the glossary at the top, waterproof fabrics are rated on both their waterproof-ness and their breathability.

Waterproof ratings are measured by the ability of a section of fabric to withstand a column of water resting upon it. The minimum height of this column, or the ‘hydrostatic head’ as it is also known, is one metre high, which is a lot of water if you stop and visualise it. High-end waterproof fabrics top out at a hydrostatic head of 30m, which is enormous as a visual image.

For general use in mild rainy conditions, you’re going to struggle to overcome anything over 5000mm of hydrostatic head (HH). Where things get tricky is in really bad conditions, or if something starts to force water through. Carrying luggage in a backpack or hip pack? You’ll need a higher rating as the weight of the pack can squeeze water in. High winds can modify things too, as high-velocity raindrops can batter their way in through lesser membranes. The same would also be true if you are riding very quickly towards a raindrop, or, compounding both, riding fast into a headwind and driving rain.

The flip side of this is that as membranes get more waterproof, with smaller pores, they also get less breathable.

Breathability is the flipside, and potentially more important for riding in generally damp conditions. Breathability, as mentioned before, is the ability of a set area of fabric to allow water vapour to pass through it in a 24-hour period. More breathable, the harder you can ride before you get sweaty. If you run hot you’ll need a more breathable jacket, in simple terms.

Breathability is affected by the DWR status, but also the outside conditions. As it relies on both a temperature and humidity differential to work best (your body heat basically forces the sweat out). If you’re somewhere warm and humid the jacket isn’t going to breathe nearly as well as somewhere cold and dry. They aren’t magic.

The trick is finding a jacket that balances both the right level of waterproofing for your activity, and the right level of breathability. It’s what makes the now critically endangered Shakedry such an appealing prospect as it is both extremely waterproof and extremely breathable, meaning it can keep you dry in a range of conditions and activity levels. It also means that while we can suggest jackets that work well, it is very much body and condition-specific, and also why for racing-level outputs, many riders simply opt for a softshell.

Waterproof fabrics for cycling

It’s easy when buying a waterproof jacket to think “what’s the most waterproof option I can buy for X price?”. I’ve done it, I’ve seen many others do it, and it’s natural to assume that more waterproof = more being dry. Sadly it’s not the case. If you opt for a Gore-Tex Pro cycling jacket and use it in anything but the most extreme conditions, you will probably be a sweaty mess very quickly. It’s why jackets, especially when constructed from the more waterproof three-layer fabrics, tend to also feature large vents like pit zips that can be used to dump heat when it’s not torrential.

As a general guide, you’re going to want something of at least 10,000mm of hydrostatic head for cycling in the rain, but you wouldn’t want to wear a pack or ride at high speed into a headwind. Beyond that, it’s up to you where your needs lie, but above 20,000mm and you’re into ‘very waterproof’ territory, as far as cycling is concerned.

Breathability, you definitely want a rating of over 10,000 for anything beyond pootling about. Given that there are more waterproof fabrics than you can shake a stick at, it doesn't really serve any purpose to list them all. Given that Gore is the most confusing and the most sought-after, it makes sense to run through the range in general terms. All have a waterproof rating of over 28,000mm:

Gore-Tex - 2- or 3- layer, the basic option. Not so breathable as 'Pro' or 'Active'

Gore-Tex Pro - The extreme option. Hyper-waterproof, relatively breathable but overkill for cycling applications

Gore-Tex Paclite - Less breathable than the others, but a focus on packability. Best for an emergency layer rather than regular use

Gore-Tex Active - This is the high output option, in general terms. Extremely breathable, but not so breathable as Shakedry. Significantly more durable however

Gore-Tex Shakedry - Ultra waterproof, hyper-breathable, and extremely flimsy.

Additionally, I hope the above information has given you a bit more background and enables you to make the right choice. The key to making the best purchase, as is almost always the case, is to be honest with the kind of riding you’re going to do.

Will joined the Cyclingnews team as a reviews writer in 2022, having previously written for Cyclist, BikeRadar and Advntr. He’s tried his hand at most cycling disciplines, from the standard mix of road, gravel, and mountain bike, to the more unusual like bike polo and tracklocross. He’s made his own bike frames, covered tech news from the biggest races on the planet, and published countless premium galleries thanks to his excellent photographic eye. Also, given he doesn’t ever ride indoors he’s become a real expert on foul-weather riding gear. His collection of bikes is a real smorgasbord, with everything from vintage-style steel tourers through to superlight flat bar hill climb machines.