Walker rides a new wave

Life after racing for one of Australia's best

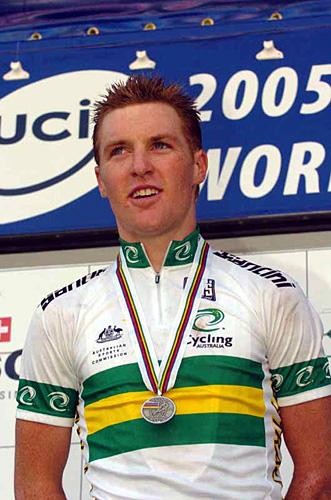

It was an audacious attack late in a tough race that had whittled the field to a handful of contenders. Storming out of the group and quickly establishing a lead that would never be threatened, Will Walker, the young man who had taken silver in the U23 road race at the previous year's International Cycling Union (UCI) World Championships in Madrid, Spain, had won the Australian road race national championship.

It had the local and international cycling press talking... a star was born.

That was in January 2006. Four years later, Walker had ridden for one of Europe's biggest professional teams, been to the Vuelta a España in the same season he signed for Rabobank's senior squad plus he'd ridden the Giro d'Italia... and had then retired. Almost five years after taking that silver medal behind Dmytro Grabovskyy the Victorian was forced to find a life off the bike at the tender age of 24.

It was a cruel twist to this story of a rider who was destined to be a solid general classification contender and a possible hilly Classics champion. Such outstanding success at a young age (he was 21 when he beat the nation's best in the hills around Adelaide to take the green-and-gold jersey) should have been the precursor to a long and fruitful career.

Walker suffers from a heart condition called tachycardia however, which means his heart rate is susceptible to massive fluctuations, especially if placed under duress - the kinds of stress associated with professional cycling, for example. Consequently, the former national champion was forced to gain a medical certificate certifying he could race or find a new occupation on the sidelines.

Having chosen the latter, Walker has brought the same energy he delivered in those early years to his new life, where he runs the Australian distribution for Nalini clothing and recently called the shots as directeur sportif for the Malaysian national team at the 15th Tour de Langkawi, held early last month.

"The process [of adjusting to life off the bike] is there already - it's worse being a director because you think about all the tactics on the road and you just think about all the times you made mistakes," begins Walker.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"And when you were racing, at the end of the day, you'd be pretty pissed off! You'd think, 'I've got the chance next year and the year after and 10 years worth of chances...' Now suddenly I'm like, 'Hang on, all those chances I was thinking I had, they're all gone! Those breakaways I could have been in...'"

Walker endured an annus horribilis in 2009 - the result of a massive crash in training the previous year and then the aforementioned heart condition, which set in early last season. It hit hard during January's Tour Down Under, when he was riding for ProTour outfit Fuji-Servetto.

He recalled that during the race's second stage his heart rate was suddenly fluttering around 300 beats per minute and he was traveling at less than 30km/h. It was easy to tell something was seriously wrong.

He explains that his health issues not only affected his body but also his mind, which is obviously crucial to success as a professional racer. "A lot of times I missed those breakaways because my head wasn't right because I had the heart problems. You become low on confidence and in the last year of riding I didn't get in any breaks because my head just wasn't right," he says.

"Even if I had a health certificate to race - which is why I stopped - I would have been very ordinary anyway. It was better that I couldn't get that and I had to stop, because it's not good to be, 'the next talent' and suddenly be someone who's not that good anymore."

Calling the shots in the tropics

Walker was recommended for the role with the Malaysian national team by fellow Australian and Victorian cycling personality John Beasley, who continues to work extensively with the Asian country's track set up, and has enjoyed success in recent years.

He arrived in Malaysia three weeks before the Tour de Langkawi and was frank about his initial observations: "We had to change a lot of things. They were so far behind the times with everything... it's been a bit of an experience for me," Walker explains. "We've changed everything - now they understand about racing, tactics; they were in nearly every breakaway."

Despite not winning a stage, Walker says that the team's riders took massive steps in their development, thanks in large to his input, although Walker places the credit squarely on his charge's shoulders.

"They were pretty attentive - sometimes there was a break of three and we had two there and I thought, 'Guys, take it a little bit easy'. They were pretty geed."

As for his future in the role, Walker is literally taking it one race at a time. "I'm still doing the Nalini distributorship in Australia and it's a full-time job, but I've just come on the races with these guys part-time, so that's pretty good," he says.

"What we looked at originally was a yearly position but I'm not locked into anything yet - it'd be just an aim to develop Malaysian cycling; whether it goes for a year or two, or a couple of months... I'm not sure just yet. It's up to me to decide."

Walker believes the secret to improving the Malaysians' performance is to expose them to more racing. That could mean a stint in his home country, which would suit his busy schedule well. "So far it's been pretty good - I think if they went to Australia to race they'd do well in the local Scody Cup races and the like. At least if they race well there they can look at what they can do in the future," he says.

'Youth is wasted on the young'

And while Walker enjoys a hectic schedule - in addition to running his business, he makes regular trips to visit his fiancée in Italy - he doesn't see himself adding to this with a permanent role as a directeur sportif. He says that his relative inexperience in comparison to those in similar roles within the professional ranks counts against him.

"I was speaking to somebody else about this - I think all the pro directors have years of experience and then they can pass that on to riders," Walker explains. "If I was a director, younger than the riders with experience, I don't think that would work.

"I think it'd be a long process for me to become a director at a ProTour team, but maybe in a smaller team it could always be a possibility," he adds. "I don't want to be somebody who's in a position he shouldn't be in, to start with, at least.

"It could be a good thing to do after riding 10 Tours de France - like a Stuart O'Grady or someone like that - but I've just done a couple of years as a professional and not even had the experience of winning races, so for me to tell somebody how to do something when I haven't actually done it myself... it'd be cool to do as a job but it wouldn't be right."

Will's bro

One of four boys in the Walker family, Will's brothers Johnny and Nicky are professional cyclists (with Footon-Servetto and Holowesko Partners respectively) but it's his other sibling, Robbie, who could have made the Olympics before any of the others.

A professional snowboarder, Robbie regularly features in magazines and movies dedicated to that sport and loves the lifestyle it brings. "He [Robbie] does the full pro lifestyle thing - when I spoke to him about the Olympics he was like, 'I don't know... It's not really for me, I just do the movies and the comps'," says Walker.

"I think when he saw how much it was on TV he might adjust his stance, however. I don't know how it is in snowboarding, but from my perspective they're pretty relaxed... they're like, 'Ah, yeah, the Olympics - it's on TV but it's just a gold medal.'

"They're pretty relaxed about it but now I think he might try and go for it in the next four years. He's one of the best in the world, so if he aimed for it I'm sure he could do pretty well."