Vincenzo Nibali – 7 moments that defined his career

Italian bows out of professional cycling at Il Lombardia after 18 seasons

Vincenzo Nibali rides his final race at Il Lombardia on Saturday, bringing the curtain down on a career that has spanned some eighteen seasons. When he first turned professional in 2005, there were four Italian teams in the newly-created ProTour, Lance Armstrong had yet to announce his first retirement and Hein Verbruggen was still the UCI president.

The lie of the land changed several times in the intervening period, not least in Italian cycling, but through those years of flux, Nibali was a near constant. He rose briskly through the opening seasons of his career before reaching the top table of Grand Tour contenders at the age of 25.

Remarkably, he would stay there for most of the next decade. Nibali shared his first Grand Tour podium with Ivan Basso in 2010, and his last with Primož Roglič and Richard Carapaz in 2019. In between, he became only the sixth rider in history to win all three Grand Tours, landing the Vuelta a España in 2010, the Giro d’Italia in 2013 and 2016, and the Tour de France in 2014.

There were Monument victories, too, at Il Lombardia in 2015 and 2017, and at Milan-San Remo in 2018, as well as near misses in Italian colours, most notably when he crashed out of the Rio 2016 Olympics while he was within touching distance of gold.

All told, Nibali racked up 52 wins across his career, but those numbers only tell a part of the story. In Nibali’s peak years, risk-averse strategies were almost de rigueur in the biggest events, but he raced with a sense of invention that often bucked that trend. His early, all-out assault at the 2014 Tour was a case in point, as was the late onslaught at the Giro two years later.

It didn’t always come off – witness his ill-fated solo effort at Il Lombardia in 2011 or his late disappointment at Liège-Bastogne-Liège the following April – but therein lay a part of Nibali’s appeal to the watching public. Even when he wasn’t the best rider in a race, he was often the best chance of something interesting happening.

It remained that way even in his final Giro in May, when Nibali – at 37 years of age – somehow propelled himself into the contest for the podium places in a race that was otherwise high on suspense but low on excitement.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Ahead of Nibali’s final race, Cyclingnews looks back at some of the defining moments of his career, while the gallery above offers an overview of his eighteen seasons in the peloton.

Giro d'Italia 2010 – The breakthrough

Even before turning professional with Giancarlo Ferretti’s Fassa Bortolo team in 2005, Nibali had been hailed as the coming man of Italian cycling, but the big breakthrough at the top level took time to materialise. On moving to Liquigas in 2006 following the demise of Fassa Bortolo – and the infamous Sony Ericsson sponsorship hoax that followed – Nibali developed gradually, cutting his teeth in Grand Tours by helping Danilo Di Luca to Giro d’Italia victory in 2007.

By the time Nibali placed a promising 6th on the 2009 Tour de France, his steady trajectory had been rather overshadowed by the altogether more dramatic arc of his compatriot and contemporary Riccardo Riccò, whose career rose steeply with all-action displays on the Giro in 2007 and 2008 and then collapsed, beginning with his positive test for CERA on the 2008 Tour. No matter, Nibali was not unduly discouraged. "That 2009 Tour made me understand I could eventually fight for victory in a Grand Tour," he said later.

Nibali was already 25 years old when he stepped into the limelight in earnest in the summer of 2010. His season had been built around another tilt at the Tour, but his schedule was torn up in early May when Franco Pellizotti was among the first riders snared by the biological passport, eventually receiving a two-year ban for blood doping. Liquigas opted to draft Nibali into their Giro line-up alongside Ivan Basso, and his entire career took flight that same month.

Liquigas’ victory in the team time trial in Cuneo put Nibali into the maglia rosa, and though he lost the jersey in a crash on the rain-soaked gravel stage to Montalcino, he recovered to play a key role in Basso’s eventual victory, while helping himself to stage victory over Monte Grappa and to third overall in Verona. The headlines that afternoon in the Roman Arena belonged to Basso – back in pink after his ban for his involvement in the Operacion Puerto blood doping scandal – but the future was assuredly Nibali’s.

A little over three months later, he rode into Madrid in the maillot rojo of Vuelta a España winner after fending off Ezequeil Mosquera’s late onslaught atop Bola del Mundo. He was on his way.

Giro d'Italia 2013 – The coronation

The sliding doors moment of Nibali’s career came in the summer of 2009, when he headed Dave Brailsford’s shopping list for the first Team Sky roster. Nibali resisted those overtures to stay at Liquigas, though he may have questioned the wisdom of that decision when he found himself on the third step of the podium of the 2012 Tour behind two of their riders, Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome - neither of whom had looked remotely like a potential Grand Tour winner when the Italian was first approached by Sky.

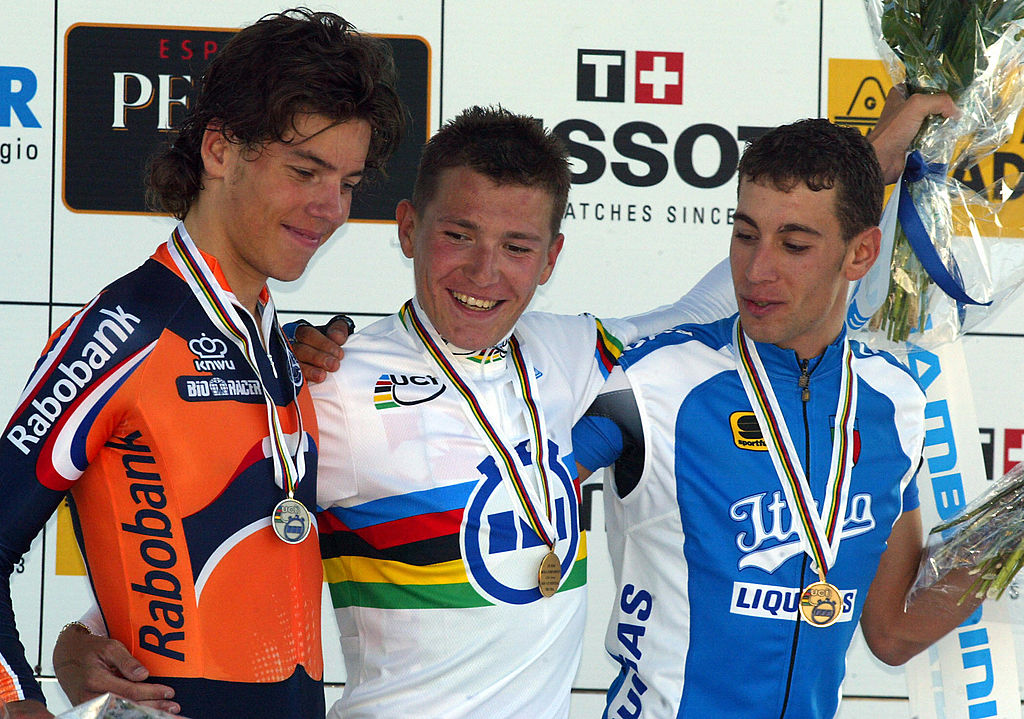

It's difficult to say whether Nibali would have won more in the colours of Sky, but he would surely have won differently. Had he joined the British team, it’s very possible that his Grand Tour strategy would have been based around his qualities as a rouleur, given that he had, after all, been third in the under-23 time trial at the 2004 Worlds.

“There are lots of riders who went to Sky and didn’t manage to express themselves well, and then others who did,” Nibali told Procycling in late 2018. By then, of course, Nibali had long since established a reputation as the seemingly instinctive counterpoint to Sky’s more measured tactical approach.

Nibali’s first victory in Astana colours at the 2013 Tirreno-Adriatico showcased that dichotomy. When Froome surged clear to win the key summit finish at Prati di Tivo, the race looked to be following Sky’s preordained script, only for Nibali to tear it up with a race-winning attack on the muri around Porto Sant’Elpidio two days later.

At that May’s Giro, Nibali set out from Naples as the joint-favourite alongside Wiggins. It quickly became clear that Wiggins was not as adept as Nibali on the sinuous, punchy finales that punctuated the race’s long swing through southern Italy. Nibali proceeded to land a devastating psychological blow when he limited his losses on Wiggins to just 11 seconds in the 55km time trial to Saltara at the end of week one.

Wiggins would abandon the race in the second week, at which point the Giro turned into a procession. Nibali buttressed his lead in the Alps at Bardonecchia, won the mountain time trial to Polsa and then capped his overall victory with a solo triumph in the snow atop Tre Cime di Lavaredo.

“We weren’t inferior at Astana,” Nibali said years later, when it was put to him that his decision to reject Sky was something akin to Francesco Totti turning down Real Madrid to stay at Roma. “In those years, Astana was one of the strongest teams of all, with me, Fuglsang, Westra, Landa – all riders of the top level. If we weren’t Real Madrid, then we were Barcelona…”

Tour de France 2014 – The exhibition

By any measure, Nibali had remarkable 2013 season. Only a most surprising Chris Horner denied him a Giro-Vuelta double, and were it not for an untimely crash, he may very well have won the Florence Worlds to boot.

That long campaign was followed, however, by a decidedly unspectacular start to 2014. By the eve of June’s Critérium du Dauphiné, Alexandre Vinokourov’s patience was reportedly wearing thin, with La Gazzetta dello Sport reporting that the Astana manager had sent Nibali a formal letter telling him that his performances were not commensurate with his earnings.

It later emerged that a similar, er, motivational missive had been sent to everybody on the Astana roster. Certainly, directeur sportif Giuseppe Martinelli seemed unperturbed by the commotion when contacted by Cyclingnews that morning. “It’s important to be competitive at the Dauphiné," Martinelli said when he picked up the phone. "But the main thing is to take another big step in building his condition for the Tour."

Nibali was still subdued at the Dauphiné, where Froome and Alberto Contador engaged in a slugging match out ahead, but he would, as Martinelli predicted, hit his stride in time for the Tour. In the hilly finale in Sheffield on stage 2, Nibali laid down a marker by attacking to claim stage victory and the maillot jaune, and he would continue in the same aggressive tenor when the race hits the cobbles three days later.

On a day of constant rain, Froome abandoned the Tour after an early crash, while Contador struggled on the pavé. Nibali, by contrast, took flight, cruising into the winning break with teammate Jakob Fuglsang. Although Lars Boom stole away for stage victory, Nibali placed a significant down payment on overall victory.

By the time Nibali won atop La Planche des Belles Filles at the start of the second week, the race was already over as a contest. Contador had been forced out by a crash and the men now chasing – Jean-Christophe Peraud, Alejandro Valverde and a young Thibaut Pinot – were simply not at the same level.

The remainder of the Tour became an exhibition, as Nibali added mountaintop wins at Chamrousse and Hautacam. It would surely have been a closer-fought race had Contador and Froome stayed in the contest, but Nibali’s superiority that July brooked no argument.

Il Lombardia 2015 – The redemption

At times, Nibali’s 2015 season felt like a mirror of the previous twelve months. Another low-key spring campaign was followed by another Italian road title. And, after a hefty setback at La Pierre Saint-Martin on the Tour, Vinokourov was back with another instalment of his ongoing tough love TedTalk: “He needs a mechanic for his head, something is broken.”

Although Nibali recovered sufficiently to win at La Toussuire in the final week – in the process upsetting the yellow jersey Froome, with whom tensions had already simmered early in the race – the miracle turnaround never materialised, and he had to settle for fourth place in Paris.

A month later, Astana opted to send Nibali to the Vuelta as part of a triumvirate with Fabio Aru and Mikel Landa, though they never even got a chance to quibble about the leadership hierarchy. Nibali was expelled from the race at the end of stage 2 after he was caught on camera taking a tow from a team car as he chased back on following a crash.

At first, Nibali returned to his villa in Lugano, but after a week or so where the walls seemed to draw in a little tighter each day, he called his father Salvatore at home in Messina: “I’m flying down. Take some time off work, you can follow me with the scooter.”

For ten days, Nibali trained in relative seclusion, while his young stablemate Aru rode to overall victory at the Vuelta. The year had been a trying one, both due to the pressures of defending his Tour title and the uncertainty over Astana’s WorldTour licence following a spate of doping cases. Now, Nibali had just a few races left in which to change the narrative.

On returning to action, Nibali placed second at the Coppa Agostoni, and then won the Coppa Bernocchi and Tre Valli Varesine, but his eyes were on the grandest end-of-season prize. In 2010, Nibali had crashed on the rain-slicked descent of Colma di Sormano at Il Lombardia and a year later, he squandered his hand with an overly ambitious attack on Madonna del Ghisallo.

There would be no error this time around. Diego Rosa helped to tee up Nibali’s first effort over the top of the Civilgio, and he still had Pinot for company come the final ascent of San Fermo della Battaglia, but he would not be denied. Nibali soloed into Como with a Monument to his name and his place in the firmament of Italian cycling restored.

Giro d'Italia 2016 – The comeback

After struggling on the Dolomite tappone and again in the Alpe di Siusi time trial on the penultimate weekend of the 2016 Giro, Nibali continued on the same downward trend when the race resumed after the final rest day. By the time he reached Andalo at the finish of stage 17, he was down to fourth overall, 4:43 off Steven Kruijswijk’s maglia rosa and over a minute off the podium. When Nibali rode into the scrum of journalists waiting for him on the finish line, he kept his comments brief: “I'm not myself, I have no explanation.”

By that juncture, conversation seemed to have turned from whether he could win the Giro to when he might abandon it. Some Italian reporters turned up in the lobby of Nibali’s hotel that evening looking for more insight than he was initially willing to give. "Why do you want to wound my pride even more? I'm already in pieces," he lamented when he walked past on his way to dinner.

Nibali eventually agreed to speak briefly with La Gazzetta dello Sport, but while he confirmed he would finish the Giro, he offered no sense that he believed he might yet bend the race to his will, noting that he would undergo blood tests to check for underlying illness. “For me these are humiliations,” he said. “But I'll get to Turin. I can't give up.”

Nibali made it to Turin alright and, somehow, he got there in the maglia rosa too. Even now, six years on, it’s a feat that seems to defy any neat explanation, though that didn’t stop some from being offered. In his press conference after the final stage, Nibali revealed that he had suffered from intestinal issues in the Dolomites, while his father told RAI that he had reverted to using 172.5mm cranks ahead of the final three stages, having switched to 175mm at the start of the season.

Whatever its genesis, the turning point came on the snow-banked upper reaches of the Colle dell’Agnello on stage 19, where, for the first time on the race, Nibali began to ride with something of the vim of old. He continued pressing as the descent began, and his pace forced the hitherto unassailable Kruijswijk into an error. The Dutchman crashed heavily and suddenly Nibali’s path to victory had widened considerably.

Nibali soloed to victory at Risoul that afternoon, but Esteban Chaves did enough to move into pink, 44 seconds clear of the Sicilian. The momentum, however, was all with Nibali. Thanks to a grand offensive from Astana on stage 20, where the late Michele Scarponi was especially prominent, he shook off Chaves on the road to Sant’Anna di Vinadio to claim a most improbable overall triumph, and perhaps the defining victory of his entire career.

Across three weeks of racing, Nibali shone on just two stages. Somehow, that was all he needed to find a way to win.

Milan-San Remo 2018 – The heist

In some ways, that 2016 Giro was a race Nibali could ill afford to lose, given that he was in the process of negotiating the biggest payday of his career, namely his move from Astana to the nascent Bahrain-Merida team. The new squad was built around Nibali, and while he had a little more freedom to build his own race programme, he also carried the bulk of the responsibility to bring results in those early seasons.

Nibali lived up to his side of the bargain in his first season with the team, which yielded podium finishes at the Giro and the Vuelta, as well as a fine solo victory at Il Lombardia. His 2018 campaign, meanwhile, was built around the Tour, but that lent a rare opportunity to build towards a mini peak in the spring.

Even so, Nibali’s low-key early-season campaign suggested that he was travelling to Milan-San Remo more in hope than in expectation. He had placed third at La Classicissima in 2012 after attacking on the Poggio, while he ignited the race with an offensive on the Cipressa two years later, but if he was named in previews for the 2018 race, it was as a courtesy afforded by his pedigree rather than an obligation demanded by his seemingly non-descript form.

Peter Sagan, as ever in that era, was the man to watch. And watch him is what everybody did on the Poggio. Only the unheralded Krists Neilands dared to go on the offensive. Nibali, ostensibly riding to protect Sonny Colbrelli's interests, decided to test the waters and set out in pursuit. The rest is history.

“When I saw we had 20 or so seconds, on the last part of the Poggio, where the gradient was harder, I decided to go hard,” said Nibali, who realised he was clutching the chance of a lifetime when he crested the summit alone in front. After cutting a tight trajectory through the hairpins on the descent, he had enough in hand to ensure he reached the finish on Via Roma just ahead of the fast-closing chasers.

Giro d'Italia 2022 – The farewell

When the 2020 Giro was postponed until October amid the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, host broadcaster RAI built its advertising campaign around Nibali, who pedalled alongside computer-generated renderings of past champions to the strains of ‘Nessun Dorma.’ At the modern Giro, no matter the eventual winner, Nibali was always the star.

But even that old certainty began to fray around the edges during Nibali’s two-year tenure at Trek-Segafredo. Second place – ahead of Roglič, no less – at the 2019 Giro had suggested Nibali might yet surpass Fiorenzo Magni as the oldest ever winner, but he never scaled such heights at Trek, placing a distant seventh in the pandemic-delayed 2020 edition and then struggling to 18th after an injury-plagued build-up a year later.

When Nibali signed a one-year contract with Astana-Qazaqstan for 2022, the subtext was clear, and the open secret was finally announced publicly in the Processo alla Tappa studio after stage 5 of the Giro in his hometown of Messina. The previous afternoon, Nibali had lost over two minutes atop Mount Etna and the remainder of his Giro, it seemed, would now amount to little more than a lap of honour. “I want to try to do something on this Giro,” Nibali said that afternoon as he made his way towards the sickle-shaped harbour for the crossing to the Mainland, but it seemed more an expression of hope than a statement of intent.

And yet, like Zinedine Zidane at the 2006 World Cup, something seemed to stir once he realised his time on this stage was hastening to its end. After limiting his losses on the Blockhaus, Nibali continued to rise in the overall standings through the second week, capped by a fine display in the miniature epic to Turin on stage 14.

Come the third week – his third week – Nibali was suddenly in touching distance of a podium finish, but it was a mixed blessing. He had wanted to mark his valedictory Giro with a stage win, but now he no longer had the freedom of movement necessary to try. He would be hemmed in by his own consistency en route to fourth overall in Verona. But then again, maybe that was the most fitting way to sign off on a Giro career where consistency was the hallmark.

For all his flourishes, for all the daring descents and unexpected, Nibali’s greatest qualities were more mundane but no less valuable: endurance and longevity. He didn’t inspire extremes of adulation like Pantani, nor did he enjoy a polarising rivalry like Moser and Saronni.

Instead, much like Felice Gimondi, he was that rarest of things: a guarantee. His final Giro only confirmed what his home nation surely already knew. They'll miss him when he’s gone.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.