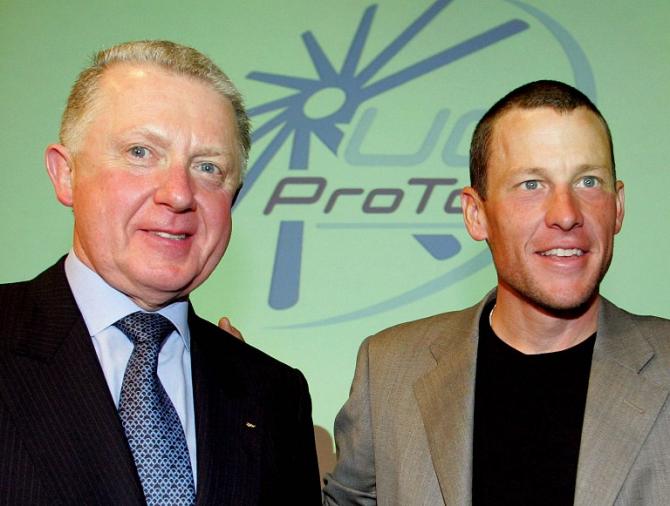

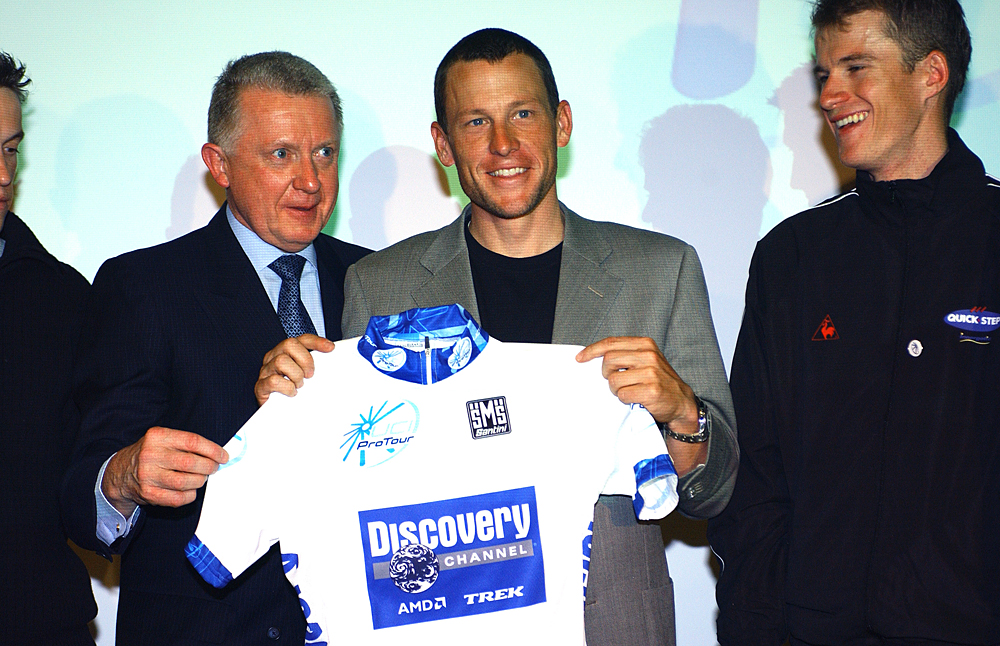

Verbruggen's defiant legacy at the head of cycling

Jeremy Whittle remembers the former UCI president

Hein Verbruggen's presidency of the International Cycling Union (UCI) was dogged by controversy and scandal. Jeremy Whittle remembers his dealings with the former UCI President, who died earlier this week.

For the most part, Hein Verbruggen hated the media. As President of the UCI during the first – and perhaps the worst — of the Great Doping Scandals of the past 20 years, the Festina Affair, he spent the aftermath berating journalists and critics for their damning coverage of that crippled Tour de France.

The letter he sent to me in the autumn of 1998 called me a 'demagogue', a rabble-rouser, as if, long before 'Fake News' became such a get-out clause, I had invented the police raids, arrests, rider protests and walkouts that had characterised that year's race.

Despite his bluster, however, he was a hugely influential figure within world sport, and within the Olympic movement. He was also a fiercely confrontational interviewee.

When, a few years after Festina, he agreed to meet for an interview in Los Angeles, he shook my hand, bypassed a 'hello' and began the conversation by saying: 'You write too much about doping.'

As doping scandals proliferated in cycling, attacking the media became a default stance for the UCI under his presidency, with fierce critic Paul Kimmage being one high-profile target. But there were others across Europe, all of whom were berated and targeted by Verbruggen.

The blighted and catastrophic Tour de France of July 1998 was the catalyst for the founding of WADA, the world anti-doping body that quickly became Verbruggen's nemesis, despite it having been created to accelerate progress in the war on dopers.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Almost immediately, there was conflict between the UCI and WADA. Presided over by Dick Pound, WADA's slanging matches with Verbruggen and, latterly, Lance Armstrong, the UCI President's pet project, became legendary.

Pound had long believed Verbruggen, seduced by commercial considerations, was turning a blind eye to the evils within his sport. The Canadian never felt that the Dutchman was really willing to tackle the spread of doping.

"Verbruggen's forte as a professional was in marketing," Pound once told me. "He wasn't prepared to rock the boat."

Verbruggen was quick to retaliate.

"Mr Pound is not objective. He's the sheriff who shoots everything that moves. WADA should be above all that and he should establish proof before he speaks. Athletes have the right to defend themselves – even if it's with the cheapest excuse."

But Verbruggen always aggressively fought his corner, shooting down any negative messengers, labelling every whistleblower from within the peloton, from Christophe Bassons to Filippo Simeoni, as failed, bitter and, even more cruelly, as 'little riders'.

Verbruggen's own version of his personal history painted a different interpretation of events. The Dutchman, describing the period prior to his tenure of the UCI Presidency as "an era when doping flourished", always maintained he had made a difference.

"There were insufficient controls, not enough regulation or professionalism," he said, back in 2005. "A group of people within the sport saw that things couldn't go on like that, [race] organisers like Jean-Marie Leblanc, team managers like Roger Legeay, and others within the UCI. Now we have a rule book and much better controls for doping."

But it was his longing to break cycling in America, the holy land of commercial growth in sports marketing, and his unsettlingly cosy relationship with Armstrong, that most damaged his reputation, both within cycling and at IOC level.

As the Legend of Lance grew, so did Verbruggen's defensive dismissiveness of any who voiced a sceptical view. That morning in Los Angeles in 2005, Verbruggen waved away the allegations against Armstrong, writing them off as mere 'gossip'.

"If you saw what Lance has to go through! I think they controlled him maybe five or six times last Christmas. That's out of competition, at seven o'clock in the morning, at his house."

The success of Armstrong, the comeback kid, and the marketability of this all-American hero, was a godsend for an administrator who'd grown weary of the bickering of 'old Europe'. For a while, as the networks flocked to the Tour de France, Armstrong ranked alongside Tiger Woods in popularity terms.

But was Verbruggen really so starry-eyed about Armstrong that he was blinkered to the suspicions over his performances, or did he collude willingly in a cover up?

Those – like Armstrong – who defend Verbruggen's actions (or lack of them) during the years of rampant growth of EPO use, argue that — without proper protocols and a reliable test — there was nothing he could do.

"What was Hein gonna do?" Armstrong insisted when I interviewed him in 2015. "Go to 1997. What do you do? You know that everybody's using EPO...

"There was nothing to do," Armstrong said. "We now know all these guys — the UCI, the IAAF, FIFA — operate the same. They're sitting on this stuff, thinking, 'If we nuke this, our sport is burned to the ground…'"

Certainly, the CIRC report of 2015 was condemnatory, citing a façade of concern over doping but accusing the UCI of ensuring that the earlier Vrijman report, commissioned by Verbruggen, into allegations of doping against the American "reflected the UCI's and Lance Armstrong's personal conclusions".

Despite the findings of CIRC, Verbruggen always remained defiant. "I have studied the CIRC report and it confirms what I have always said: there have never been any corruption cover-ups, complicity or corruption in the Lance Armstrong case."

*Jeremy Whittle's new book, 'Ventoux,' is out now, published by Simon and Schuster.