Ultimate Étapes: Stage 16: In Marco Pantani's Wheeltracks - Book Extract

Riding the Stelvio and Mortirolo

This extract is from Ultimate Étapes by Peter Cossins, published by Aurum Press.

Although Marco Pantani bagged his first professional victory 24 hours before this stage of the 1994 Giro d'Italia, his status as one of the sport's legendary climbers has its foundation in this epic day over two of the race's most iconic summits – the Stelvio and the Mortirolo. Pantani later admitted he didn't know much about the Mortirolo before he raced up it, although he had been told it suited his qualities as the most spring heeled of specialist climbers. The rider dubbed Il Pirata ('The Pirate') softened his rivals up on its precipitous slopes before delivering a sabre like victory thrust on the final climb of the Valico di Santa Cristina. In his wake, he left a trail of devastated riders, notably defending champion and five-time Tour winner Miguel Indurain, whose hopes of retaining the title had been shattered.

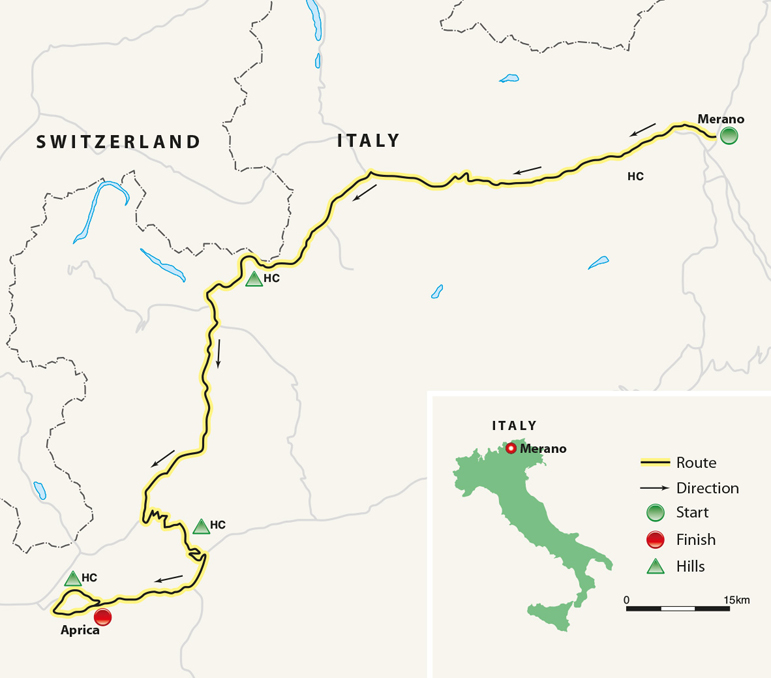

This ride commences in Merano, which lies in the German-speaking South Tyrol region of Italy. Heading east on the Strada del Passo dello Stelvio up the Vinschgau, the fertile upper part of the River Adige valley, the route passes the apple orchards and vineyards for which this area is renowned. This road, which goes on to cross the Reschenbachpass into Austria, can be busy, although those who want to avoid the traffic can escape onto the Vinschgau bike path that runs parallel to but often some distance from the highway.

Most of the traffic and almost all of the trucks disappear when the Strada del Passo dello Stelvio bears off to the left at Spondinig, making a beeline for Prato allo Stelvio, then continues towards the pass on a road built up above the roiling waters of the Suldental. The river's often frantic progress in the opposite direction is an obvious indication that the long climb of the Stelvio is now under way, although the change in gradient is not too radical for the moment. However, the appearance of huge, snowcapped peaks sealing up the top end of the valley suggests that some serious climbing is not too far distant.

The change comes in Trafoi, where huge, tidily stacked piles of wood outside every building attest to the harshness of the winters in this village, which sits surrounded by huge peaks at an altitude of 1,300 metres. The road rises straight through the village until it meets the Schöne Aussicht/Bella Vista Hotel directly in its path and rebounds off this establishment into the first of four-dozen hairpins. For the next 17 kilometres, the gradient will remain above seven per cent, and sometimes well above.

This incredible road owes its existence to the desire of the Habsburgs to construct a route between Lombardy and the Vinschgau. Designed to encourage trade and, particularly, to ease military movements in this highmountain region that was long a part of the Austro–Hungarian empire, the road was designed by Carlo Donegani. The Brescia architect has been fêted for this exceptional feat of engineering ever since. A Mecca for car drivers, partly thanks to BBC's Top Gear voting it 'the greatest driving road in the world', the Stelvio is equally popular among those on two wheels. Motorcyclists gleefully slalom up and back down its slopes, often startling cyclists so rapid is their approach.

Both flanks of the pass are impressive, but the classic ascent is this eastern side, which features 48 of the Stelvio's 75 hairpins. Initially the road climbs through pine forest, the trees creating a barrier that on a quiet day often leaves cyclists in a haven of peace, the only sounds their breathing and the whirr of chain over sprockets. These interludes allow those who are dependent on leg- rather than horsepower the opportunity to reflect on the brilliance of Donegani's creation, which enables altitude to be gained with relative ease and compensates to some degree for the prolonged effort required to achieve the summit.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

As at Alpe d'Huez, the hairpins are numbered in reverse order. Initially there is some distance between them, but bend 42 brings a change. Sweeping right around it you're onto the first 'ladder' of switchbacks, although the density of the trees cloaks this marvel of engineering. The road rises quickly to reach bend 35, which sits about a thousand vertical metres below the summit. By the next gaggle of hairpins, beginning at bend 32, the trees are starting to thin out, allowing stunning views across to the Ortler massif on the southern side of the valley. Climb a little further and the Franzenshöhe hotel and restaurant comes into sight and, high above it, there's a first glimpse of the top of the pass.

Looking down from the summit at the highest 20 or so hairpins, you could be forgiven for thinking that they were something from a child's drawing of a fantastical mountain road. It really is that wonderful, and seeing that view will be ample reward for negotiating those final bends, which lift the road from 2,188 metres at the hotel to more than 2,700 metres at the summit.

The strain of riding at this kind of altitude can make this section into a bit of a breathless slog, but there is good reason to relish the next halfdozen kilometres. For a start, the gradient does ease a little above the Franzenshöhe. It also helps that from bend 14 onwards the hairpins are heaped so compactly, the rock and stone walls above one switchback supporting the lower part of the next, that the top of the pass is not only very evident but almost seems to come more quickly than expected.

The last few bends are among the steepest on the mountain, but by that point the thrill and relief of knowing you've just about made it kicks in. At the top there are cafés, restaurants, hotels, a bank, a surprising number of shops selling tacky mementos and, often, lots of motorcyclists high-fiving each other having managed to make it to the top aboard high-powered machines. It feels slightly surreal to arrive in this busy little hub having climbed so high through a landscape where just about the only sign of man's incursion has been the incredible road. It does, though, mean you can reload with something warm while you drink in that view and dwell for a few minutes on what is a crowning achievement for any cyclist.

The descent to the Mortirolo

From the summit, the road plummets past the Swiss border post and the turn onto the Umbrailpass towards the ski resort of Bormio. Although less numerous than on the other flank, there are still hairpins aplenty, interspersed with longer, straighter sections. After he had tied up the 1980 Giro on this stage, partly thanks to the daredevil descending of teammate Jean-René Bernaudeau, Bernard Hinault admitted that he'd feared for his wellbeing on these extremely fast sections, where unlit tunnels add a significant element of danger. Just before Bormio, a left turn heads up the equally impressive Passo di Gavia. But those set on an encounter with the Mortirolo will continue through the stylish resort on the SS38 for another 30 kilometres, where a rather nondescript left turn at Mazzo di Valtellina heads away from the valley floor and into trees that conceal the first vicious ramps of the Mortirolo, also known as the Passo di Foppa.

There are no fewer than 33 hairpins on this gruelling ascent, some going with the precipitous incline rather than attempting to take the edge off it. Between kilometres two and nine, the gradient is north of 12 per cent, suffocating enough even without trees crowding in on both sides of the narrow ribbon of a road, cutting off any hint of a cooling breeze and often shutting out any view that might offer even the most temporary distraction from this gruelling test. Although the late Marco Pantani (whose feats on this climb are commemorated at bend 11) dismissed any rider who used anything more than a 23 sprocket, it's wise to opt for something much bigger, a 27 at least. As you twiddle towards the summit, ponder on where doping's excesses took the sport and riders with turbo-charged blood around the turn of the millennium.

Between bends five and four, with the gradient already easing, the pines finally give way to rough pasture, which continues to the summit. Unlike the majesty of the Stelvio pass, this is a very unremarkable point and there's little incentive to dawdle before the far less recipitous drop into Monno and Edolo. Climbing once again as it continues on through Aprica, the road's final test is the Valico di Santa Cristina.

Although far less exacting than the Stelvio or Mortirolo, it should not be underestimated, especially for those who have already had these two monsters gnawing savagely at their reserves. The average gradient may be a more palatable eight per cent, but this is a pass of two halves. The first, on the main SS39 road, is steady. However, just before this road switches south and down into the Valtellina, the route swings right onto the Via Maranta, heading for the hamlet of Mezzomonte, and takes on a quite different complexion.

This narrow road, which hasn't featured on the Giro's itinerary since 1999, is tightly tree-lined, often mossy and damp, and is seriously steep. Climbing in this muggy, sometimes cloying realm, where traffic is almost non-existent, it is not easy to summon up the hysteria that greeted Pantani when he flew up these slopes in 1994. His exploit more than doubled the TV audience, from three million watching as the stage crossed the Stelvio to more than seven million by this point. A cycling legend was born on these slopes, although you would never guess that from the very discreet brown sign at the Santa Cristina's summit.

For those wanting to loop back towards the Valtellina, the road from the pass towards Trivigno and onwards leads back to the top of the Mortirolo. Otherwise, follow the drop down into the resort town of Aprica, which is fast and should be taken with care given the dampness under the trees, to complete what is sure to be an unforgettable day's riding.

Sportives

The Granfondo Stelvio Santini takes place in early June. Established in 2012, it has already become a favourite for sportive-baggers as its longest 151-kilometre route features both the Mortirolo and the Stelvio. The three route options all start in Bormio and finish atop the Stelvio, tackling this epic ascent from the Bormio side. The short and medium versions don't include the Mortirolo, which some may regard as a good reason for missing the longer option, but if you've come this far… Information: www.granfondostelviosantini.com

At the end of August, the Passo dello Stelvio Park authority closes both sides of the Stelvio to motorized traffic, enabling riders to have what is effectively a pro-like closed road over one of Europe's highest passes as their playground. The descent off the Umbrailpass into Switzerland is also closed, which allows participants in the Stilfserjoch Radtag (the Stelvio Cycling Day) the option of a stunning circuit including both ascents of the Stelvio, a test that's never yet been set to the pros. Information: www.stelviopark.bz.it/it/radtag

Based on Aprica and taking place at the end of June, the Gran Fondo La Campionissimo ('champion of champions') was established in 2015. Thanks to some canny route planning, all three routes (85, 155 and 175 kilometres) feature the Mortirolo, although the shortest option tackles the easier side from Edolo. The two longer routes both cross the outstanding Gavia pass and the Mazzo ascent of the Mortirolo. The longer of them goes on to the Santa Cristina. Information: www.granfondolacampionissimo.it/en

Other Riding

It would be almost criminal to be in Bormio and not take on the Gavia. The narrow road to the 2,621-metre pass entered cycling legend in 1988, when a snowstorm enveloped the Giro and the USA's Andy Hampsten emerged from the whiteness to claim the pink jersey, which remains his country's only success in that Grand Tour. It is entirely possible to complete a circuit from Bormio comprising the Mortirolo and Gavia via Ponte di Legno.

After looking north from Bormio to the Stelvio, east to the Gavia and south to the Mortirolo, to the west there are more Giro favourites in the shape of the Foscagno, Eira and Livigno passes. The penultimate stage of the 2010 corsa rosa featured all three of these 2,200-metre-plus ascents before returning to Bormio for the passage over the Gavia and a finale on the Tonale Pass, where Swiss rider Johann Tschopp claimed by far the greatest success of his career. This gave a total distance of 178 kilometres of almost constant climbing or descending, which most would be advised to split over two days of riding.

Fact File: In Pantani's Wheeltracks

Route Details

Country : Italy

Race: 1994 Giro d'Italia (stage 15)

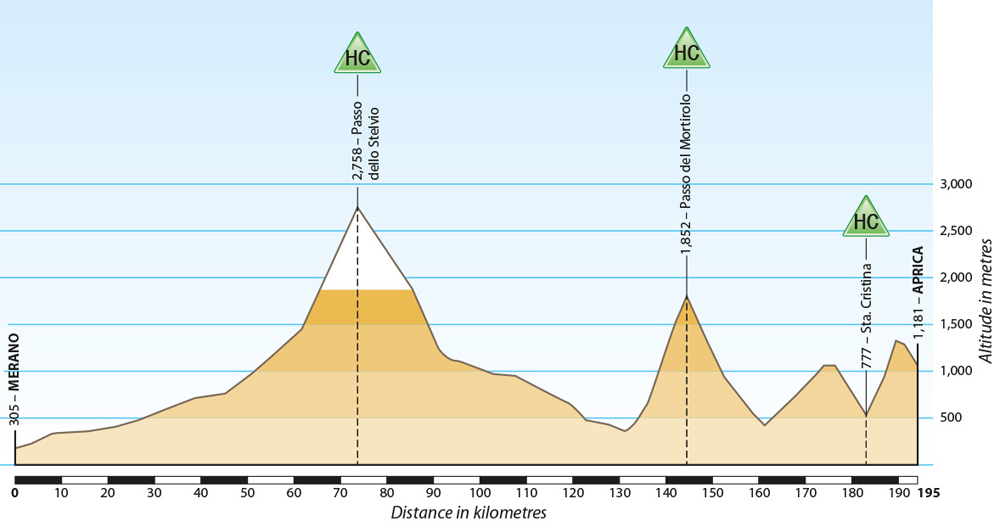

Route: Merano–Aprica/Valtellina, 195km

Terrain: High mountains

Climb Stats

Passo di Stelvio

Height: 2,758m

Altitude gained: 1,832m

Length: 25.7km

Average gradient: 7.2%

Maximum gradient: Short sections

at up to 15%

Passo del Mortirolo

Height: 1,852m

Altitude gained: 1,300m

Length: 12.4km

Average gradient: 10.5%

Maximum gradient: 18%

Valico di Santa Cristina

Height: 1,427m

Altitude gained: 1,024m

Length: 12.52km

Average gradient: 8.2%

Maximum gradient: 15.5%