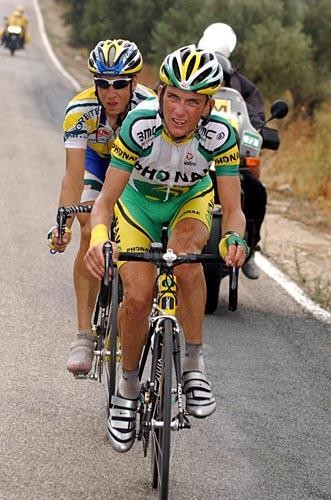

Tyler Hamilton's last stand

The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) dismissed Tyler Hamilton's appeal against his ban for blood...

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

News feature, February 15, 2006

The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) dismissed Tyler Hamilton's appeal against his ban for blood doping on February 10. In its findings, the CAS explained exactly why none of Hamilton's arguments were convincing enough. Cyclingnews' Chief Online Editor Jeff Jones analyses the arbitration report in this special news feature.

The Tyler Hamilton blood doping case has reached its next, and arguably most significant phase, with the Court of Arbitration for Sport's recent decision to uphold Hamilton's appeal against his two year ban. In handing down its verdict late last week, the CAS found that "the HBT (homologous blood transfusion) test as applied to the samples delivered by Hamilton at the Vuelta was reliable, that on September 11, 2004 his (Hamilton's) blood did contain two different red blood cell populations and that such presence was caused by blood doping by homologous blood transfusion, a prohibited method under the UCI rules. As a consequence of this anti-doping rule violation, the CAS Panel has confirmed the two years' suspension imposed on Hamilton."

Hamilton will be able to race again on September 23, 2006, as the CAS ruled that Hamilton voluntarily accepted a provisional suspension from September 23, 2004, and the two year ban should apply from that date, not from April 18, 2005, when the American Arbitration Association (AAA) first found him guilty. In theory, that means he could race again for a ProTour team - à la David Millar - although, unlike Millar, Hamilton doesn't appear to be admitting his culpability.

In reading the CAS's final 34-page arbitration report, many questions that were raised by Hamilton and his defence in the initial AAA/CAS hearing in 2005 are answered, while some remain frustratingly closed. The report concludes that Tyler Hamilton did use someone else's blood to win the September 11 time trial in the 2004 Vuelta a España. And there is still an open case in front of the CAS, initiated by Viatcheslav Ekimov and the Russian Cycling Federation, that he used foreign blood to win the Olympic time trial in Athens.

The arbitration report explains this in typically formal language, and can be read in full here. What follows is an attempt to distill its most significant points for family reading.

Background

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The arbitration panel that considered Hamilton's appeal consisted of the president, Mr Malcolm Holmes QC, a Sydney, Australia barrister; and arbitrators Ms Maidie Oliveau, attorney-at-law in Los Angeles, USA, and Mr David W. Rivkin, attorney-at-law in New York, USA. The appellant, Tyler Hamilton, was represented by Los Angeles, USA lawyers Mr Howard Jacobs and Ms Jill Benjamin, while the Respondents were the US Anti-Doping Agency, represented by Mr Richard Young, attorney-at-law in Colorado Springs, USA, and Mr Travis Tygart, director of USADA legal affairs; and the UCI, represented by Mr Philippe Verbiest, attorney-at-law in Leuven, Belgium. The hearing took place on January 10, 2006 in Denver, Colorado, USA.

The story of Hamilton's positive test is now well known. On September 11, 2004, he won a time trial stage of the Vuelta and underwent a blood test. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) accredited lab in Lausanne, Switzerland used the new homologous blood transfusion (HBT) test to determine that his sample showed signs of a mixed red blood cell count, and took this as evidence that he had transfused someone else's blood. This is, of course, illegal under WADA and UCI rules.

On a peripheral level, Hamilton's Phonak teammate Santiago Perez, who finished second in the 2004 Vuelta behind Roberto Heras, underwent a blood test on October 5, 2004 in Lausanne. He too was found to be positive for a homologous blood transfusion, and was given a two year ban in February 2005. In response to a fairly obvious question, Cyclingnews understands that Hamilton and Perez have different blood types.

Then there were the results of some of Hamilton's other blood tests taken throughout the year 2004. During the Athens Olympics in Athens, Hamilton rode and won the individual time trial on August 18. He was tested using the HBT test, and his A sample was found to be positive. But, due to a lab error, his B sample was accidentally frozen and was unable to be tested. Thus, Hamilton could not be declared positive on the basis of those two tests alone.

Rewind back to April 2004, when Hamilton was subjected to blood checkups as part of the UCI's health program. This was during the time of Liege-Bastogne-Liege and the Tour de Romandie, both races that Hamilton had won in 2003. As with all riders, Hamilton's haematocrit, haemoglobin, and percentage of reticulocytes (new red blood cells) were tested.

The UCI uses a simple method to determine whether a rider is "unfit to race", and whether there is a likelihood that blood manipulation has taken place. The so-called HR-OFF Stimulation Index (SI) is the relationship of the amount of haemoglobin and reticulocytes in a rider's blood. If this value is over 133, then it means that there are a lot of red blood cells floating around, but there are not so many reticulocytes, which means that the body isn't producing the extra cells. Taking EPO or using any kind of blood doping will give high HR-OFF SIs and a low reticulocyte count.

According to an article in the Los Angeles Times, published in April 2005, Hamilton's HR-OFF score was 123.8 on April 24, the day before L-B-L, where he finished ninth. Five days later on April 29, just as he set out to successfully defend his Tour de Romandie title, it was a very high 132.9, with a corresponding reticulocyte count of 0.22 percent and a haematocrit level of 49.7 percent (the UCI limit being 50). He had another blood test on June 8, 2004, and both this and the April 29 sample were tested using the brand new HBT test, which was then in the process of being validated.

As a result of these tests, the UCI's medical officer Dr Mario Zorzoli sent a letter to Hamilton and the Phonak team on June 10 informing them that "the blood checks that took place during the Tour de Romandie 2004...showed an abnormal profile" and that they showed "strong signs of possible manipulation." Thus, there was evidence that Hamilton was using homologous blood transfusions well before the Athens and Vuelta tests took place, even if it couldn't be used to declare him positive. In addition, he was warned that he would be "closely monitored" for the rest of the season.

The final blood tests of note took place in December 2004 in January 2005, at Hamilton's instigation. He submitted a sample of his blood taken on September 20 to be screened at MIT using flow cytometry, and this time, it only showed the presence of one blood type. However, MIT is not a WADA accredited lab, nor was it one of the labs instructed on how to use the HBT test.

Establishing guilt

According to the WADA Code, an anti-doping violation "may be established by any reliable means". In other words, it was not necessary for the USADA and UCI to rely on a positive test to demonstrate that Hamilton was guilty of blood doping. There was more to consider than just the Vuelta sample, and these additional tests were claimed by USADA to provide "independent evidence of doping" and to "corroborate" the results of the Vuelta test.

Hamilton's lawyers claimed that the use of the UCI health checks in such a manner was "inappropriate and unauthorised." This is unsurprising, not only in the context of this case. It could be quite significant in the Russian Cycling Federation's appeal to try to strip Hamilton of his Athens gold medal, despite only having a positive A sample to go on. A CAS ruling on that is expected soon.

The thrust of the appeal

In representing their client, Tyler Hamilton's legal team left no avenue unexplored in trying to overturn the AAA/CAS's original decision. In fact, there was new evidence brought to light that addressed some of Hamilton's previous questions relating to the AAA/CAS decision.

One of the most important submissions made by Hamilton was the assertion that the HBT test was not sufficiently validated by the time it was used in the Vuelta. The test is based on flow cytometry, which can detect mixed red blood cell populations by binding surface markers to a fluorescent tag. It has been used for decades in several areas of medicine, most importantly to detect maternal/foetal bleeding as well as to match patients for organ transplant. But it had never been used as part of an anti-doping test, its rate of false positives is unknown, and there was documented concern regarding "false positives".

Hamilton also claimed that the UCI, USADA and some of the labs were involved in a "concealment of documents"; that there had been "inconsistent statements of witnesses"; that there had been "serious doubt" raised by the co-creator of the HBT test concerning the Lausanne Laboratory test methodology, in an email to the IOC dated 13 August 2004 which "was never retracted"; there were problems with controls used in the HBT test; There was "disagreement among USADA's own experts over the meaning of the basic terms of the WADA positivity criteria."; and the test methodology was flawed because there had been a disregard for the "previously recommended 5% threshold for inappropriate and nonscientific reasons."

As a second line of defence (if the test and the test results were found to be watertight), Hamilton submitted that there were other possible causes for a mixed red blood cell count: disease, bone marrow transplant, intra-uterine transfusion or chimera. The first three had already been ruled out during the 2005 AAA/CAS hearing, and when DNA tests performed on Hamilton showed that he wasn't a chimera, Hamilton was left with having to prove that the test itself (or how it was applied) was dodgy.

Dismantling the appeal

The arbitration panel dismissed Hamilton's arguments as follows:

Firstly, to the claim that there should have been a threshold applied to test results, the panel stated: "The test criteria require a clearly definable peak to be produced on testing. This is an objective fact. It may not require a numerical percentage threshold, but it is either there or it is not...In one case the HBT test found a blood sample with a mixed population down to 0.4%."

With regard to the disagreement over positivity criteria, the panel stated, "The test criteria used in anti-doping are conservative in that the positivity criteria adopted by WADA and applied in this case require positive results for two antigens whereas in the usual clinical use of flow cytometry, one may be sufficient. In the case of the Vuelta sample mixed populations were found for three antigens."

As for problems with controls used in the HBT test, the panel cited evidence from "leading practitioners and scientific researchers" that the test had been carried out in a rigorous manner and "that there is no possible washover effect from the controls to the samples." And although the Lausanne lab was not yet officially accredited to perform the test [this occurred on October 4, 2005], directors of three other accredited labs - including the one that developed the test - were satisfied that Lausanne had done things correctly.

When accreditation was finally given to Lausanne a year later, the panel noted that "the methodology at the time of the visit in October 2005 was substantially the same methodology as had been used in the Lausanne Laboratory at the time of the Vuelta test." During that time, there were minor changes made to improve the sensitivity of the test, without affecting its specificity.

Hamilton's legal team challenged the testimony of some of the witnesses that were called by the Respondents, claiming that some of them had made "inconsistent statements" and that their testimony should be rejected. After obtaining some of the inter-laboratory communications (see below), Hamilton did indeed find some differences between some of the witnesses' oral testimony and their own emailed material. However, while the panel acknowledged several instances of inconsistency, it did not consider them important enough to cast doubt on the test.

Turning to the "concealment of documents" accusation, it transpired that the CAS hearing was adjourned in September 2005 so that Hamilton could have access to further documents from the Lausanne Laboratory, the Athens Laboratory and the Sydney Laboratory. He was supplied with these from the Sydney lab, and he and his lawyer visited the Athens and Lausanne labs in person to inspect their records. He later confirmed that he had "virtually unrestricted access to all documents and records of the Athens Laboratory."

Thus, the panel found "that there was no concealment such as would cast doubt on the validity of the test. On the contrary, the complete and open production of documents and the totally unfettered access that was given by the Athens Laboratory to the Appellant confirms that those involved in the implementation and validation of the test had nothing to hide."

One of the documents obtained by Hamilton was an email from the test's co-creator, Dr Michael Ashenden, to the International Olympic Committee's (IOC) Dr Patrick Schamasch, dated August 13, 2004, in which he raises serious doubts concerning the Lausanne lab's test methodology. Hamilton claimed that the email "was never retracted, concerning a methodology that was never changed."

Dr Ashenden wrote that there were "anomalies in results emanating from the Lausanne lab...In particular, I wish to make you aware that recent results from Lausanne, including a false positive for one antigen in a recent blood sample, are unreliable and do NOT represent the methodology being considered for implementation by the IOC in Athens. Nor are any speculations or concerns raised by Lausanne as an outcome of their recent testing valid - since these conclusions are derived from an inappropriate application of methodology. The test used in Lausanne is NOT the same test used in Sydney and Athens."

Taken on its own, this email is quite damning, especially as it was not produced in the initial AAA/CAS hearing. But, contrary to Hamilton's claim that "it was never retracted", subsequent communication between the Sydney and Lausanne laboratories addressed all the concerns.

It turned out that the Sydney lab was wrong, as Dr Ashenden stated in a later email to Lausanne: "the sample that you found to have two peaks WAS in fact a mixed cell population, and was NOT a false positive as we originally stated." Dr Ashenden apologised for the confusion, and went on to acknowledge that any the other concerns relating to the methodology used were unfounded, and were "due to the fact that the Lausanne Laboratory was still finalising software adjustments and establishing optimal titers for their new flow cytometer."

Again, the CAS arbitration panel was satisfied that this email exchange did not cast doubt on the HBT test or the Lausanne lab's competency to perform it.

Finally, and perhaps the key part of Hamilton's appeal, was the false positive rate of the test, or rather the lack thereof. A false positive is a result that shows a mixed red blood cell population when in fact, there is none. A chimera would not produce a false positive, as it is a real result showing a mixed RBC population.

There was no false positive study conducted during the validation of this HBT test, and WADA experts have testified that they didn't need to do one. It is certainly possible to produce a false negative, as evidenced by Dr Ashenden's August 13, 2004 email to the Lausanne lab. The Sydney lab mistakenly identified a sample as negative when in fact it should have been positive, as the Lausanne lab showed. But what about false positives?

"There is no chance of a false positive when following the methodology implemented in Athens," wrote Dr Ashenden in his initial email. This implies that there is a real chance for false positives to occur if the laboratory has not followed correct procedure. But no-one knows what this chance is, because it hasn't been studied. The positive predictive value of the HBT test is therefore unknown.

It would be nice if we could believe the scientists when they tell us that their test is perfect, but hundreds of years of experience has shown this to be a dangerous approach. Take, for instance, the test developed to detect EPO in urine samples. This is a WADA validated test, but has recently been found to have problems giving false positives. These false positives were not taken into account when the test was first put into use.

Hamilton went further to try to prove that the HBT test could produce false positives, alleging - from his perusal of the lab records - that over 20 samples (not his own) were falsely reported as positive. But in each case, USADA was able to show the reason behind a "false positive" to the satisfaction of the panel. Most were either deliberate errors, equipment malfunctions, or actually not reported as positives in the first place. But it does show that there is a finite probability of a false positive, even if it does rely on very bad lab work.

Unfortunately for Hamilton, he could not prove that the Lausanne lab had followed an incorrect procedure or had an equipment malfunction when analysing his own sample. Thus, he must be considered a true positive.

The verdict

In weighing everything up, the arbitration panel was convinced that Tyler Hamilton's appeal was not sufficient to prove that he hadn't blood doped in the 2004 Vuelta. "For the reasons described above, the Panel finds that the presence of a mixed blood population in Appellant's Vuelta sample as detected by the HBT test proves that the Appellant engaged in blood doping, a Prohibited Method, that violated the UCI Anti-Doping Rules; Chapter II, article 15.2 and Chapter III, article 21."

That won't satisfy Hamilton, nor his supporters, but the CAS is the highest court that he can appeal to on sporting grounds. As evidenced by the report, it wasn't a completely open and shut case: there is still enough doubt to convince the "true believers" that he is not guilty...but not enough to convince the arbitration panel.

Hamilton's only 'victory' was the backdating of his suspension by nearly seven months, as the panel judged that he had accepted voluntary suspension from the time he was suspended by his team on September 23, 2004. Instead of running up until April 18, 2007, his ban will expire on September 22, 2006, meaning that he could (theoretically) compete in the World Championship road race on September 24 and perhaps finish off the 2006 season.

He could also, in theory, ride for a ProTour team, as the ProTour code of ethics, which prevents teams from signing convicted dopers for four years, did not come into place until 2005. David Millar has already done so for Saunier Duval, for example, and the UCI's Enrico Carpani enlightened Cyclingnews about the rules:"The four years additional ban comes from the code of ethics decided on and accepted by the teams, and not by the UCI rules," he said. "The UCI has no power over that, so the decision to maintain and respect this agreement will be an exclusively 'internal affair' for them."

It's clear, however, that unlike Millar, Hamilton has no intention of admitting guilt. On the contrary, he is steadfastly maintaining his innocence. On his personal website, www.tylerhamilton.com, he writes that his mission is to "fight for reform within the anti-doping movement. I do support the anti-doping mission and USADA, however the current system has failed an innocent athlete and needs to change.

"Out of respect to fairness and the rights of all athletes, there should be clear separation between the agencies that develop new tests and those that adjudicate anti-doping cases. Credible, independent experts, not those who funded or developed the original methodology, should be charged with properly validating new tests.

"I don't believe any athlete should be subjected to a flawed test or charged with a doping violation through the use of a method that is not fully validated or generates fluctuating results. I will also continue to support the formation of unions to help protect the rights of athletes. My goal is to keep other athletes from experiencing the enormous pain and horrendous toll of being wrongly accused."

Finally, what happened to www.believetyler.org, a site that was set up by friends of Hamilton's to help him with his legal defence? "Believetyler.org is an informational site created to give the public the full story behind the current allegations, and to allow those who want to help to do so through an on-line donation link."

You have to use the Wayback machine to find it now, otherwise you get a 404 error. In answer to the question, Cyclingnews has been informed by Deirdre Moynihan, one of the site's founders, that believetyler.org was shut down because she wished to focus the attention on Tyler's own website, www.tylerhamilton.com. "We wholeheartedly and without hesitation support Tyler, and we will not give up until he is once again victorious on and off the bike," said Moynihan.

Cyclingnews coverage of Tyler Hamilton's blood doping case

February 12, 2006 - Hamilton appeal rejected

January 10, 2006 - Hamilton faces CAS again

November 23, 2005 - Wire in the blood II: Hamilton's last hope

November 22, 2005 - Wire in the blood: Hamilton's last hope

October 6, 2005 - CAS to rule on Hamilton case by year-end

September 13, 2005 - Hamilton case heard, but not finalised

September 6, 2005 - Hamilton appeal to be heard this week

August 21, 2005 - Hamilton racing again

August 4, 2005 - Hamilton hearing on September 6

June 21, 2005 - Still no word on Hamilton hearing date

June 16, 2005 - Hamilton appeal hearing delayed

June 3, 2005 - Hamilton appeal is go

May 18, 2005 - Hamilton appeal set for June

April 29, 2005 - Tyler's side of things: Hamilton reacts to doping ban

April 22, 2005 - Hamilton: "The fight will continue"

April 20, 2005 - Armstrong comments on Hamilton verdict

April 19, 2005 - The Hamilton decision: Is he guilty and is the science perfect?

April 19, 2005 - Hamilton's defence

April 19, 2005 - Hamilton suspended for two years

April 18, 2005 - Hamilton's defence: The vanishing twin?

April 17, 2005 - Hamilton decision expected on Monday

April 13, 2005 - Hamilton awaits

March 14, 2005 - A longer wait for Hamilton

March 11, 2005 - Hamilton optimistic, but proceedings kept open

March 1, 2005 - Distributor plays down Hamilton role in IMAX movie

February 28, 2005 - Hamilton hearing starts

February 4, 2005 - Hamilton hearing date set

December 1, 2004 - Phonak: "Black day for cycling", Hamilton confirms sacking; UCI explains

November 30, 2004 - Hamilton sacking doesn't save Phonak

November 25, 2004 - Hamilton speaks out

November 18, 2004 - WADA code opens door to Hamilton appeal

October 22, 2004 - Hamilton vows to clear his name

October 21, 2004 - Russians appeal Hamilton's gold

October 1, 2004 - Pound weighs in to Hamilton controversy

September 29, 2004 - Russia to appeal against Hamilton decision

September 23, 2004 - Official: Hamilton's Olympic B test dropped

September 23, 2004 - Phonak claims one B test negative; Tyler Hamilton's statement

September 23, 2004 - Armstrong on Hamilton

September 22, 2004 - Hamilton suspended by Phonak

September 22, 2004 - Hamilton and Phonak protest innocence

September 21, 2004 - Hamilton fails blood test