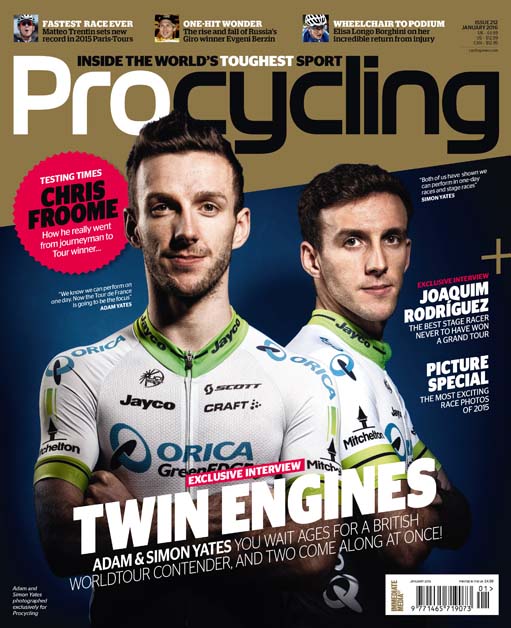

Twin Engines: Up close with the Yates brothers

Simon and Adam from Bury to the WorldTour

This feature first appeared in Procycling magazine. To subscribe, click here.

Yates brothers impress at Tour de France

Yates gets surprise victory at Clásica San Sebastián

Great Britain hoping Adam Yates can spring a surprise at the World Championships

Chaves to target Giro d'Italia top five as Yates brothers return to the Tour de France

Great Britain look to Froome, Thomas and Yates brothers for Olympic medals in 2016

The comparisons simply never stop for Adam and Simon Yates. Ever since they were juniors racing on the Manchester track, the cycling world has been fascinated by the prospect of twins competing at the highest level. Now they are riding in the WorldTour and standing on the edge of greatness. They can boast top finishes in Classics, stage races and the hardest Tour de France stages, and they’re still only 23 years old. Procycling asks what makes them different – from everyone else and from each other. And how far can this unique family go?

Grane Road, otherwise known as the B6232, rises gently west out of the Lancashire town of Haslingden towards Blackburn, past terraces of sandstone brick houses. The road follows the River Ogden before climbing to skirt the bleak heights of Oswaldtwistle Moor to the north; to the south, the scenic Musbury Heights, popular with walkers, overlook three reservoirs in the valley which are fed by the river.

On the left side of the road just outside the town, opposite a small cemetery and marking the boundary between moorland and civilisation, stands the former church of St Stephen, now the Holden Wood tea shop and antique centre. It’s an imposing building, with a tall, square tower topped by an octagonal spire. This is Adam and Simon Yates’ favourite tea shop, a regular waypoint on their training rides, just a 30-minute spin from their childhood home in Bury. It’s where they’ve arranged to meet Procycling. It’s also a small window through which we can get a glimpse of their cycling background, their roots and who they are.

The weather is typically Lancastrian: gunmetal clouds blow low across the sky, obscuring the moor above us. Rain gusts across the landscape in billowing sheets. It’s easy to imagine the Yates twins, when they were younger, racing each other along Grane Road to the shelter of the tea stop.

“We’d get home from school. Get something to eat. Go out round here with lights on in the pitch black,” says Adam. “Two hours, in the freezing cold.” Seeing the doubt on my face, he adds, “Well, you have to, don’t you?”

You can put it down to genetics or luck, why the Yates twins got so good at cycling. You can compare Adam’s organic path into professional sport, heading to France with a bit of cash from the Dave Rayner Fund to race with the amateurs and U23s, with Simon getting selected for the more structured and regimented life at the British Cycling Academy and winning a world title on the track before focusing on the road. You can conclude that given their similar genetics, nature might trump nurture when it comes to producing world-class cyclists. But really the answer to the question – why are the Yates twins so good? – is out on these Lancashire roads.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“We didn’t race against each other in the races,” says Simon, “But during training we did. You’re going up a small climb and one of us will start edging forwards. It turns into a race, full gas. That is when we race each other."

“You’re not training when you first start,” continues Adam. “You’re just going out riding. Then you start edging wheels in front and racing each other, and doing efforts. You’re not thinking, ‘Right, I’ll do 20 minutes here,’ you’re thinking, ‘Let’s have it!’ We learned to race before we learned to train.”

Those half-wheeling contests are a convenient metaphor for the Yates twins’ journey through cycling. Just when you think one has edged ahead of the other, the other comes right back. Simon was the faster starter and the earlier developer – born five minutes before Adam, you could argue that the half-wheeling started right there and then on August 7, 1992. Simon won the World Points Race Championship in early 2013, edging ahead. Adam half-wheeled him back with second overall at the Tour de l’Avenir the same year. Then Simon, with the Haytor stage win and third overall at the Tour of Britain.

And so on into 2014 and 2015. Adam nudged ahead with first overall at the Tour of Turkey. Then Simon, with a string of top-10s in the spring stage races. And finally Adam, with a win in Clásica San Sebastián. They profess not to be in competition with each other – in any case, riding for the same team, it’s their job not to be in competition with each other. But there must surely be the smallest hint that they push each other on, just as a half-wheeler on a training ride imperceptibly edges everybody’s speed up. So one more question about their early training rides around Haslingden and the West Pennine Moors: Who was better, back then?

Adam (turns to Simon): “It was you, by a little bit.”

Simon: “Still am now.”

Adam: “Oh, come on!”

A lot is made of the difficulty of telling one Yates twin from the other. But in the flesh it’s pretty easy. While helmets and distance limit the information television viewers have to work with (unless you know that at the Tour, Adam wore sunglasses with green frames while Simon’s were white), they look different in real life. It’s often reported that they are identical twins but they are actually fraternal (non-identical) twins. They don’t look the same: their noses point in subtly different directions, Simon’s smile is slightly wider, his hairline lower; their faces are a different shape. It also helps that Adam tends to wear a beard, while Simon is clean shaven. Look a bit more closely and Adam’s got a scar running down the right side of his chin. Adam’s quiff is higher than Simon’s – ever the rebellious younger brother.

Behaviourally, it’s harder to say. From the evidence of this interview, it might be possible to conclude that Adam talks a little bit more and tends to lead the conversation – he often answered questions first. But Simon’s answers were generally more assertive. It’s actually harder to tell them apart when it comes to their characters than physically – they neither blend into each other, nor act particularly differently. They’ve got the same matter-of-fact confidence as each other, and they’ve managed to develop an extremely competitive streak without becoming chippy about it, which is not straightforward. ‘Confidence’ is a subject they talk about a lot – during the course of our interview, they say the word on 16 different occasions.

But the really interesting comparison between the Yates twins is on the bike. What they have in common is that they are both extremely difficult to define as cyclists. There was a ‘Sliding Doors’ moment in their lives when Simon was picked for the Olympic Academy and Adam wasn’t, which sent Simon temporarily towards track racing and Adam towards the road. While Adam raced in France and honed his natural climbing skills, Simon was putting on a couple more kilos of muscle and getting good enough at tactics and sprinting that he won that World Points Championship race in 2013. When Adam came second in the Tour de l’Avenir that year, it looked like he was a GC rider, while Simon’s two stage wins at the same race were more opportunistic, just like his stage win at the Tour of Britain, which was one part grit, one part perfect timing, one part confidence and one part leg speed.

In 2014, Adam’s Tour of Turkey win confirmed the general feeling that he was the stage racer of the family. Yet in 2015, Adam’s best results have been in one-day races, while Simon has been the rider who performed consistently in multi-day events. Rather than say one or other of the brothers is a climber, or a stage racer, or a one-day rider, it might be more accurate to say that they’re good enough at all of those things to be able to match the specialists, yet too good at them to be labelled as all-rounders.

“You can’t pigeonhole us,” says Adam. “We’ve both shown we can perform in one-day races and stage races.”

I point out that cycling has favoured specialisation in recent years but the Yates twins are having none of it.

“How would you define Joaquim Rodríguez?” asks Simon.

“He wins one-day races, stage races, he’s up there in Grand Tours…” continues Adam. And whether deliberately or not, in asking that question, the Yates twins have given a clue of where they might go as bike riders.

“We always get asked who we look up to in British cycling,” says Adam. “But there’s nobody who is the way we are – small climbers. Froome and Wiggins were strong time triallists first and climbers second.”

The Yates twins have more in common with Rodríguez than with Chris Froome and Bradley Wiggins. Rodríguez is a climber who can win the hardest one-day races, like Lombardia and Flèche Wallonne, mountainous week-long stage races, and finish on the podium of Grand Tours. The Yates twins aren’t exactly the same – their track background means they are far more competitive in small group sprints, and while Rodríguez needs steep hills to thrive, the Yates twins are showing more potential on shallower gradients.

Rodríguez has won the WorldTour overall classification three times – his consistency and ability to get results in Classics, stage races and Grand Tours, means he can win points all year round, either by winning or by high placings. The WorldTour is seen as a by-product of winning races, rather than a win in itself but if you had to design a competition to favour riders like the Yates twins, it would look a lot like the WorldTour.

The Yates brothers grew up in Bury, just outside Manchester. Their dad, now retired and a keen cyclist, worked in a factory just outside the town, while their mother is a civil servant working at the Highways Agency.

Adam: “Not much to say, really. Bury’s nothing special. We’ve got a world-famous market.”

Simon: “Don’t forget that.”

Adam: “And black puddings. But there’s nothing special about it.”

Simon: “It’s the last tram stop outside Manchester, so you can get into town, but it’s good to get out here, to go riding. We lived in Redvales, small, quiet community. Used to be a mill town, eh?”

Adam: “It’s hard to describe because when you grow up somewhere like that it’s just normal. There was a field round the corner we used to play football on.”

Simon: “And the monkey bridge. Out near the reservoir we used to climb around on that, jumping in the river. It was a little bit dangerous.”

They graduated from the monkey bridge to mountain bikes, then track cycling as their father took them to watch, and then participate in races at Manchester Velodrome – they were track racers before they were road racers. For the 2011 season, both applied to the British Cycling Olympic Academy, which is where their paths diverged. Simon was selected, while Adam was not. British Cycling are renowned for making unemotional, hard decisions, and this is a classic of the genre, although it seems to have exercised everybody else in the cycling world more than it has the Yates brothers themselves.

“It wasn’t because I wasn’t good enough,” insists Adam. “But I just didn’t have the results to prove myself. I wasn’t devastated because I kind of knew it wasn’t going to happen. I knew I could do something but I wasn’t keen on staying in England. Racing in Britain didn’t suit my characteristics at all. I was still pretty good on a track, and pretty quick for a small guy, but I’m best going uphill. There aren’t any races here that finish on climbs.”

So Adam packed up and went to France, supported by the Dave Rayner Fund. He spent two years based in Troyes with fellow Bury native Josh Hunt, the half-brother of Jeremy Hunt, who now races for One Pro Cycling, then a year in Belfort with CC Étupes, one of the best amateur teams in France.

“It was savage, really. There are ex-pros and guys who live like pros. There’s no limit on the number of riders in a team so you turn up and see 20 guys from one team. And against that, it was just me and Josh. I loved it,” Adam says.

Results picked up when he moved to Belfort, on the Franco-Swiss border, in 2013 and started training more in the mountains. A stage win and third overall at the Tour de Franche-Comté was a precursor to his second place at the Tour de l’Avenir that year.

Meanwhile, Simon was living a more regimented existence at the Academy, which had moved back to Manchester after being based in Tuscany. He thrived but his memory is that it was every bit as hard as Adam’s existence in France, but in a different way.

“In Picardy [the Côte Picarde race] I crashed pretty heavily, on a very wet day, on a descent. I slipped out and slid for ages, until I was under a bush. My bike was broken and they didn’t see me so I got left behind. I had to get a lift off some random Swiss guy,” says Simon.

“The next week was the Toscana [Terra di Ciclismo], with a stage on the gravel roads. In the final, with 15 guys, I was thinking, I could win this, because it was a group of climbers and I was quick from the track. But somebody crashed in front of me.

“This was my crashing period. Two days later we raced a crit around Rome. It was very rainy and there was oil everywhere. I crashed in the neutral zone and in the first lap, so I pulled out and waited for my teammates to finish.”

He pauses, and adds: “I was having a few doubts around then.”

In the second half of 2013, the Yates brothers’ different paths converged again. They’d moved apart a little physically: the small differences which had existed between them as juniors had been trained and developed.

“We were still similar but Simon’s always been a bit bigger,” says Adam.

“This is probably why I was a tiny bit better when we were younger – I was a little more developed, a bit stronger,” says Simon.

The two stage wins and second overall that they gathered between them at the Tour de l’Avenir were newsworthy but it was Simon’s stage win at Haytor at the Tour of Britain, with Adam just down the hill in 14th place, which announced them as contenders on the world stage.

Haytor, in the south-east corner of Dartmoor, is a tactical climb. It has a very fast start and then the steepest part is the second quarter, where it’s easy to go too hard. Once the road hits the open moorland, about halfway up, there’s still the best part of 3km to ride and most of this is draggy and right into the prevailing westerly wind. The final stretch to the car park at the top is steep. In short, the length of the climb means that attacking early is risky, while the headwind means attacking in the middle section is equally risky. And the steepness of the final stretch means that even an early attack here probably won’t work. The best tactics, especially in the context of 2013, where a strong Sky team were focusing on defending Bradley Wiggins’ overall lead, were to allow Sky to control the climb, then jump late, at a point where top speed could be held to the line. Here, the headwind finally becomes a possible advantage – if a rider can get a gap, the chase stalls.

The racing could not have played out any better for Simon: Stefano Pirazzi attacked on the steep early section and Dan Martin went on the drag in the middle. Both were easily contained, for the reasons above. It was David Lopez of Sky who went early on the final steep section, but even that wasn’t enough. Emerging from the wreckage of his rivals’ poorly-chosen tactics, Simon Yates made one move, at exactly the right moment.

A lot was made of this win, and rightly so; he had dropped Bradley Wiggins and Nairo Quintana, among others, in the dash to the line, although he’s characteristically understated about it.

“There was a bit of a headwind and it’s not that steep a climb, so you get a lot from sitting on the wheels,” says Simon. “Everybody has the chance to win and these were the best uphill riders so I was, well, not worried, but nervous if I was good enough. I was confident that if I got to the end, I was fast enough to win. I’d just won two Avenir stages in similar fashion, so I knew I could do it.”

The story of the plucky amateur beating the seasoned professionals is a compelling one but both Yates twins see it as logical. In the past, when cycling was structured differently, a result like this would have been surprising but not now. In the past, riders were junior or amateur or professional, and there was little crossover between different categories, which meant there were huge leaps between them.

“There isn’t the massive step up in level any more,” says Adam. “The level of the U23s is already so high. We always get asked why we’re so good. It’s because when you race U23, it’s already at such an outrageously high level, that when you step up, it’s not a massive jump.”

Simon had still got the tactics right, however, and in explaining his Haytor win he shows an understanding of bike racing that he thinks is innate but is more likely to have been unconsciously and efficiently absorbed over years of track and road racing.

“Cycling’s a dynamic sport,” says Simon. “Sometimes you’ve got to take risks. I thought I’d gone too early but I managed to get a gap and it was a headwind. Once there was a gap it was hard to bring me back.”

I point out that Simon’s track background makes him a real danger in small group finishes, citing him out-sprinting Rui Costa to come second in the final stage of the Critérium du Dauphiné this year as a good example.

“The problem is that there are a lot of track guys these days,” says Adam. “Everyone’s got a little kick.”

“But it’s a lot to do with tactics, as well,” he continues. “Like I said before, we learned how to race before we learned how to train. We know where we need to be before a sprint, which wheel to be on. You know that from the track. You take it to the road and you don’t even think about it – it just happens.”

Procycling: “Well let’s talk about that. You’re obviously physically gifted but tactics make the difference between winning and not. Have you always worked on your tactics?”

Adam: “No.”

Simon: “We haven’t really worked on tactics.”

Adam: “It’s not something you can work on, if you think about it.”

Simon: “How would you work on that?”

Procycling: “By watching races, looking at finishes, talking to coaches…”

Adam: “There’s only so much that you can do.”

Simon: “We do watch a lot of races. I’m a cycling fan but I wouldn’t say I watch it to learn, it’s more to enjoy it.”

Adam: “Anything can happen. You can study a race, and then in the end it’s no use to you.”

Procycling: “Then why are you so good at racing tactically?”

Adam: “I wouldn’t even say that we’re good at it. It’s more that you just know.”

Simon: “It’s more a feel. You feel it. I don’t think that I have to be here or there in a group. You can feel that a certain guy has been strong all day, so I’ll be floating around him and in a position where I can move. It’s hard to describe. When you think about timing, you can feel when you can go. You can feel that dip in the speed, which I picked up in my track days, and that’s how I won a lot of races. Both my world titles [Simon also has a junior world title, the 2010 madison, with Dan McLay, to his name], I’ve won in the last sprint – you can feel the moment, the dip in pace, and that’s when you turn it on.”

Adam: “You don’t learn and study it, you just know how to do it.”

Wherever it comes from, Simon Yates put years of training, unconscious absorption of racing tactics and innate ability to use in that one jump on Haytor. His stage victory helped him to eventually finish third overall, 1:03 behind winner Wiggins. Simon had lost 1:33 in the time trial stage alone.

“Without the TT, I’d have won overall, eh?” he says.

To read the rest of the interview, along with interviews with Joaquim Rodríguez, Elisa Longo Borghini and Bob Jungels, and in-depth features about BMC, the Tour de San Luis, Paris’ inner-city Auber 93 team, the Ruban Jaune, Evgeni Berzin, plus a themed picture special by Tim De Waele, buy the January 2016 edition of Procycling, available in newsagents.

This feature first appeared in Procycling magazine. To subscribe, click here.