Turning a moment into a movement: Gender equality and the campaign for women at the National Hill Climb

4,100 sign an open letter for equal prize money

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The coming of autumn means one thing in the UK cycling calendar: hill climb season. Shorter, colder days are accompanied by uphill time trials, seemingly endemic to the UK and by and large run by local clubs. The season culminates in the National Hill Climb Championships, which takes place this weekend in Streatley, near Reading.

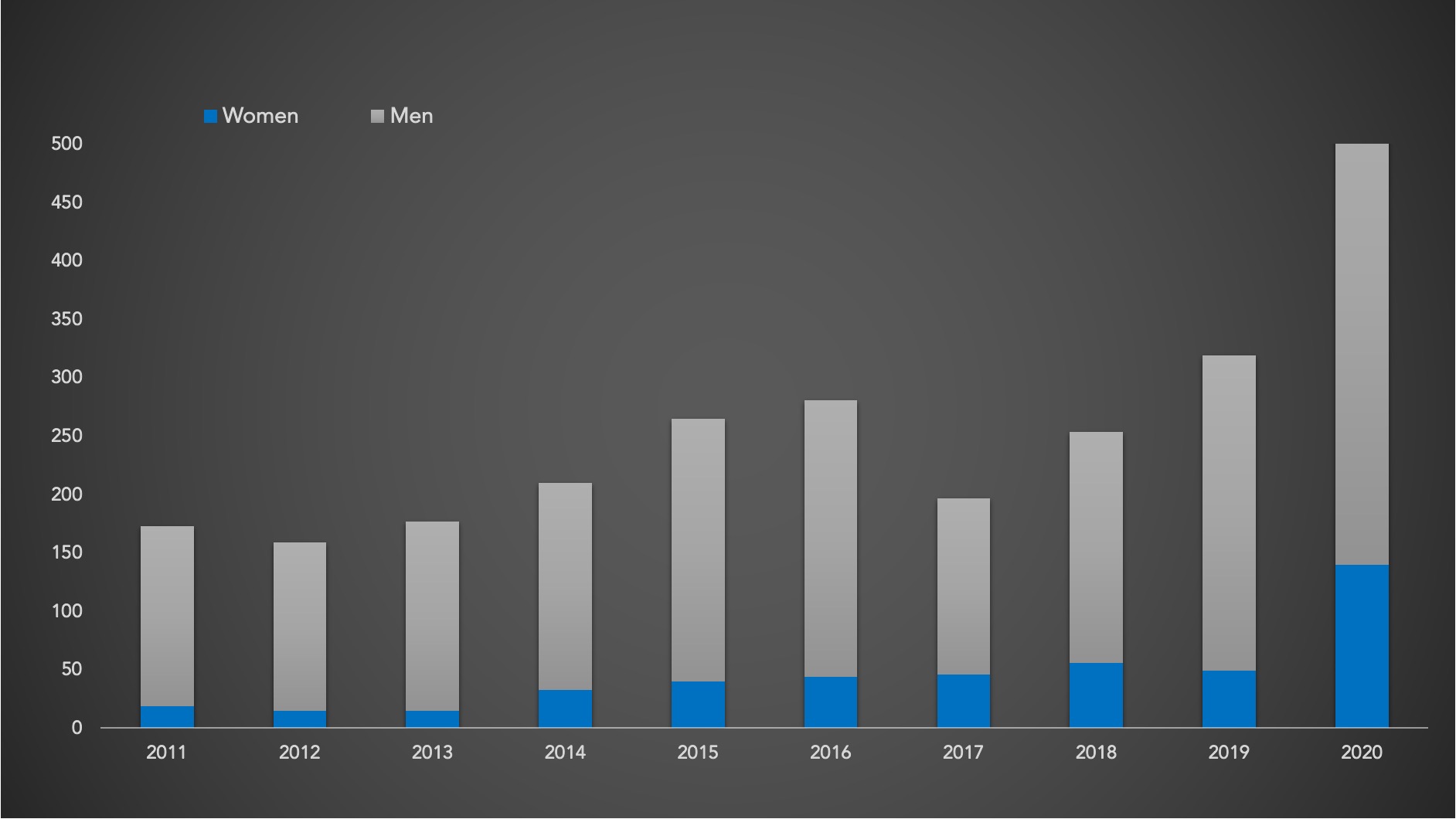

This year’s event promises to be different. Of the names on the start sheet, 140 are female – the highest number of female entrants ever to enter this national championship. At the time of writing, over 4,100 people have signed an open letter to the UK’s time trial organisation (Cycling Time Trials, CTT) asking for a rule change requiring equal prize money to the top three finishers, male and female, in each category. As well as this, women are sharing their own stories of hill climbing on social media and inspiring others with the hashtag #climbhighertogether. Combined, women are taking the issue of gender parity into their own hands and raising their voices to speak out against inequality in cycling, with a hope for lasting change.

Laurie Pestana is one of those women. Pestana first started racing bikes when she was nine. She says she’s been the ‘token girl’ on the race scene for a major portion of her life, and is pretty sick of it. Following a professional cycling career in Belgium, Pestana got into hill-climbing when she returned to study in the UK and took part in the BUCS (inter-university) hill climb.

In the time since, Pestana has put her passion for equality into a major push to see more women race this year’s national hill climb, inspired by efforts like the Helen 100 to get junior women into cyclo-cross.

Pestana’s campaign has raised the profile of the national championships, and matched sponsors to women’s entries – funding around 90 female riders to take part. But she says the solution runs much deeper than covering entry costs. The campaign makes a statement that says that women are welcome and encouraged to race, empowering them and showing that they are valued before they’ve even touched the start line.

More than half of these women will be taking part in the Nationals for the first time, which is undoubtedly a daunting prospect, but Pestana hopes the positive experience will trickle down, feeding back into local clubs and women’s cycling groups, providing new role models, and starting a grassroots movement to see more women giving hill climbs a go.

The numbers speak for themselves. Women’s entries are almost three times higher than last year, with a record 140 female names on the start sheet and it doesn’t go unnoticed that Pestana has managed to achieve this in what for many has been a testing year. That said, it’s not all been easy for her. Whilst she says the positives have been awesome – like fantastic sponsors and seeing more women getting involved – she’s also received backlash with personal and threatening messages.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But Pestana is resilient. She tells me she won’t be bullied into silence, and if people are choosing to critique her as a person then they haven’t got an argument against what she’s actually pushing for. I, for one, think she’s fantastic.

Social media has been a cornerstone of the campaign for women racing at the Nationals, and it’s not only Pestana making a splash. In response to the campaign and to encourage women to share their stories and raise the profile of women’s racing, Becky Hair started #climbhighertogether.

Hair was named as one of the top 100 women in cycling in 2019 for her efforts in inclusion of women, and is an avid and talented hill climber herself. She asks women to use the hashtag to share how they got into hill climbs and stories from their races, recognising that women’s racing sees less exposure, and looking to change that from the ground up.

“We want to start a movement, not a moment,” she says. “We want to encourage others to race, to get past those barriers, to have a go, and to feel welcomed into our community.”

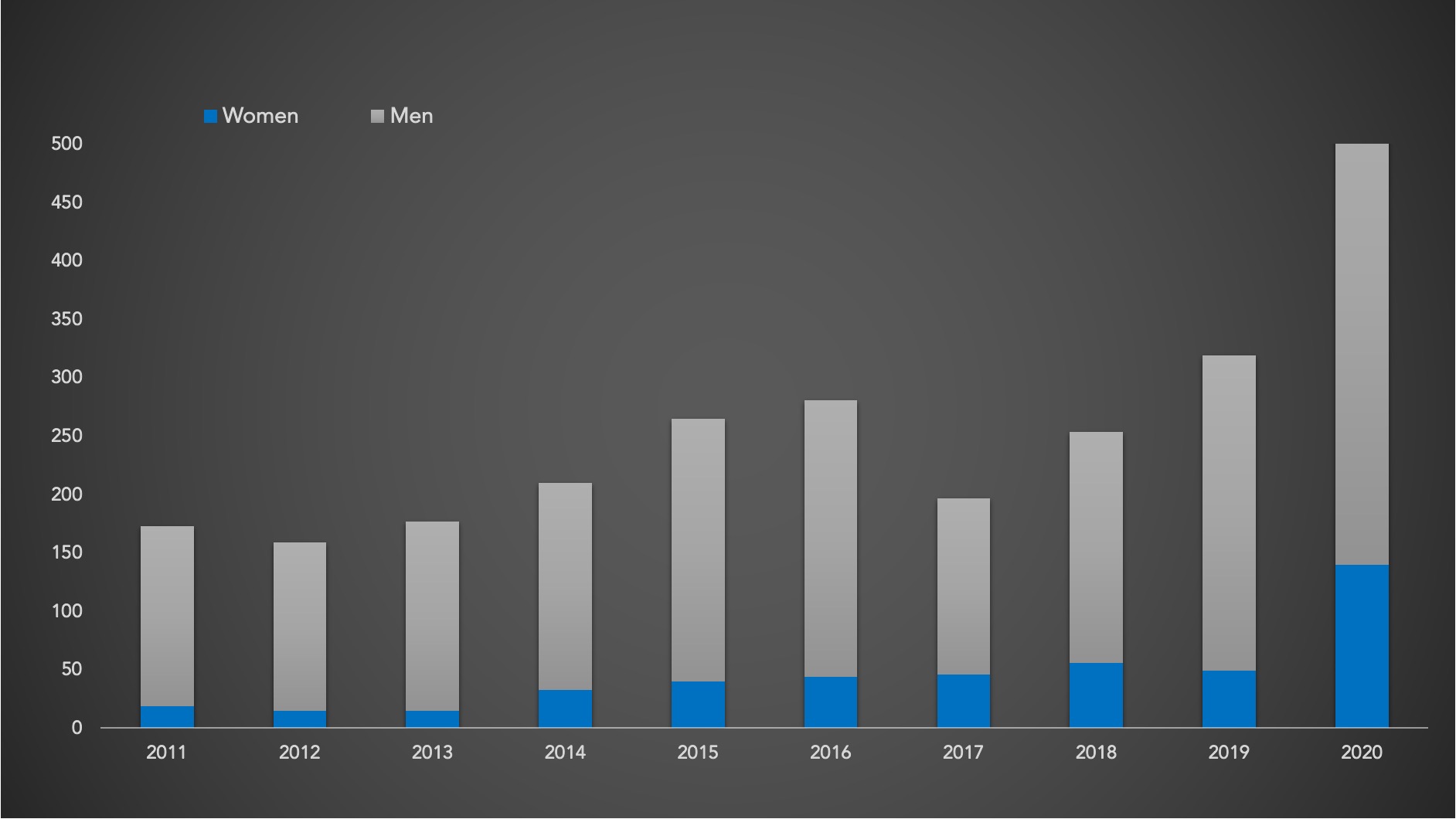

The history of women competing at the National Hill Climb is much more recent than many may realise: the men’s event stretches back to 1944, but 1998 was the first year that women were allowed to compete. In 2003, five years later, a women’s national champion was recognised, and it took until 2012 for medals to be awarded for second and third place in the women’s competition – a change driven by the hosting clubs.

In 2018, I added the section for women’s results to the Wikipedia page for the National Hill Climb. This background matters, as it shows how women have started from a position of inequality. ’Male’ has been the default for hill climbs, and this helps in part to explain the disparity in male and female entries. However, the full picture is much broader and the barriers and obstacles to women racing are numerous, and complicated.

Systemic gender inequality in the UK means that women on average do 60 per cent more unpaid work than men, which includes child care and adult care (ONS Data). In addition, men enjoy on average five hours more leisure time than women per week (ONS Data). So, it’s not surprising that women are underrepresented in sports.

I estimate that between 10-15 per cent of road cyclists in the UK are women, using an imperfect method judging by Strava segments. Therefore, the pool of cyclists drawn from to enter events is much smaller. There are additional barriers linked to that smaller pool and to the historic exclusion of women: feeling like you might not fit in, feeling like an outsider or not knowing any other women who compete in those events.

Finally, and sadly, there are the minority in the sport who reinforce the idea that women are less valid and less welcome, either through speaking to that opinion or providing events where the prizes focus on ‘overall’ placings – wording that might as well be replaced with ‘men’ in hill climbs, listing women as ‘others’ or providing extensive prizes for men with perhaps one or two for women.

This problem with prizes is about recognition and celebration of women. This relates more to the club events than the Nationals themselves, and afflicts time trials year-round, and permeates women’s cycling from grassroots to professional racing.

Inequality of prizes is a big problem, and this is not the first time women have raised their voices. In fact, many of the veterans of the hill-climb scene comment on how they are fed up of having to raise the issue. This year, despite many clubs offering equal prizes, there have been events where the prize money available for men was more than double that for women, or where prizes were listed as an overall prize and ‘ladies’ in the ‘other’ category.

For the Holme Moss Hill Climb, Nikkola Matthews contacted the organiser in advance to raise issues with the unequal prize structure and received no response. She tells me that she considered not racing in protest but decided instead to make a t-shirt to race in – reading “Equal prizes please”. On the day, she spoke to the organiser and offered a sponsor she had found to match the women’s prizes to the men’s. The organiser refused, saying that he didn’t feel it was appropriate, and further defended his position in an email to participants. The incident generated widespread discussion and support on social media, and ended with Helen Wyman (of the charity Helen 100) paying the missing prize money directly to the female racers.

There is a critique that women don’t deserve equal prizes because they don’t make up an equal proportion of entries. This fails on many levels. I struggle to think of other sports where prizes are given based on the proportion of entrants of a demographic rather than achievement within a category, and it seems beside the point anyway. We should equally value women’s success and be proactively encouraging participation – looking forwards to making cycling a better place, rather than being hung up on what it has been.

Often, defenders of the status quo are quick to point out that it’s a token anyway, and no one enters time trials for the money. If that’s so, then surely there’s more argument for creating a ‘token prize’ for women. A token prize often means an envelope, a podium photograph and a mention in results coverage – all of which raise exposure of women’s racing. Equally, it’s hard to concede the argument that prizes should be unequal because there are fewer women, given the inequality of the starting point.

Experiencing repetitive inequality of prizes drove Haddi Conant to look at what could be done to create a lasting change. Conant was given a road bike for her 18th birthday and hasn’t looked back. She now races for Lifting Gear Products/Cycles in Motion and will be competing at the Nationals. She raced her first hill-climb season last year and was shocked by some of the prizes – an issue that she took up with organisers.

The same has happened this year, on several occasions, and Conant figured it was time to sort it out properly, taking the decision away from individual organisers and taking action on the sport as a whole. Through discussion with her team, a proposal was developed to change the rules of time trials in the UK to require equal prizes for the top three finishers of each category, of both sexes. An open letter, currently amassing over 4,100 signatures, asks for this change to be considered.

Conant says the goal is to show the people at the top that there is a huge support base for this change, and it’s not just a few women. She hopes it will start a meaningful discussion to change something so deeply rooted in the sport.

“We go through the same training, race the same hill, put in the same effort and pay the same entry fee,” she says. “It’s all the same apart from the celebration at the end.”

The letter’s authors hope for an official response from Cycling Time Trials after the letter is formally presented to them.

Looking to the future, time triallist Michelle Lee wants to take this a step further. Lee is passionate about making time trialling a more inclusive, welcoming place, and co-authored a 2019 survey looking at equality in time trials. Following this, Lee and her colleagues propose a gender-equality standard and accompanying kite mark that organisers can display on promotional materials for events where the equality standard is met. The team behind it is still developing the finer details and hopes to launch the standard and mark for the 2021 season, which would allow organisers a blueprint for equality at events, and allow entrants to identify events that meet the criteria.

Women and men across the UK are fighting to equally reward and celebrate female cyclists in grassroots racing. They’re working to encourage those already riding to have the confidence to give it a go, to change the system so they compete for equal prizes and to change the dialogue so that women’s racing is recognised and celebrated in its own right, and that women are welcomed.

They share a passion for equality and a drive to make cycling a better place for the girls learning to ride bikes now, and the girls who will follow them. Fighting for your legitimacy in sport is exhausting. It is my hope that we’ll look back on 2020 as a turning point year where real change started.

Acknowledgements:

With thanks to Emily Chappell and Joe Hawksworth for their help with getting the words right, and to Becky Hair, Haddi Conant, Laurie Pestana, Michelle Lee and Nikkola Matthews for taking the time to speak to me. To the photographers who’ve allowed their images to be used – thank you. Finally thank you to all the clubs who get it right, and to those who’ve listened to us and changed.

About the author:

Alice Thomson is a cyclist and feminist from Bristol. She races for Bristol South Cycling Club, loves hills and hates inequality. Alice raced her first hill climb a few months after getting her first road bike and it was her gateway drug to competitive cycling. She has previously held the women’s record for Everesting, completed Paris-Brest-Paris (1,200km) last year, and likes to name all of her bikes. Follow her blog here, or on Instagram here.