Tour de France Pyrenees preview: The ancient and the modern

The peloton gets a second taste of the mountains this weekend

The dust has barely had time to settle on the 2019 Tour de France's only individual time trial on Friday afternoon before this year's race route dives back uphill for a second helping of the Pyrenees this weekend. And unlike on Thursday's brief incursion, it will be hoped that this time around the GC gloves will be off with a vengeance when the roads start to steepen.

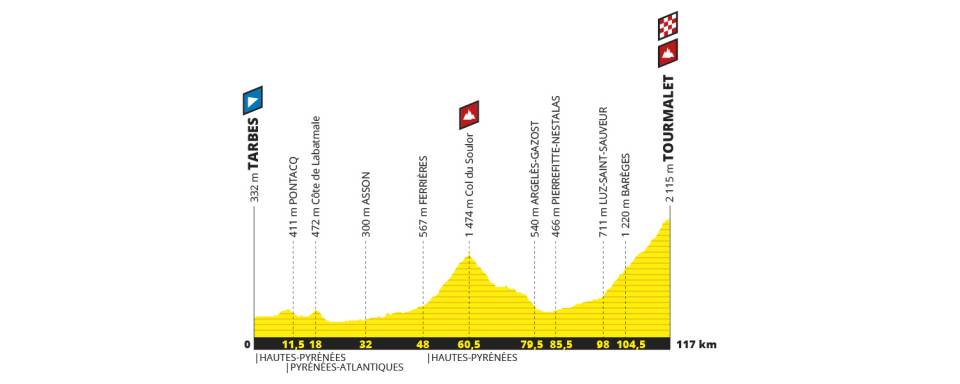

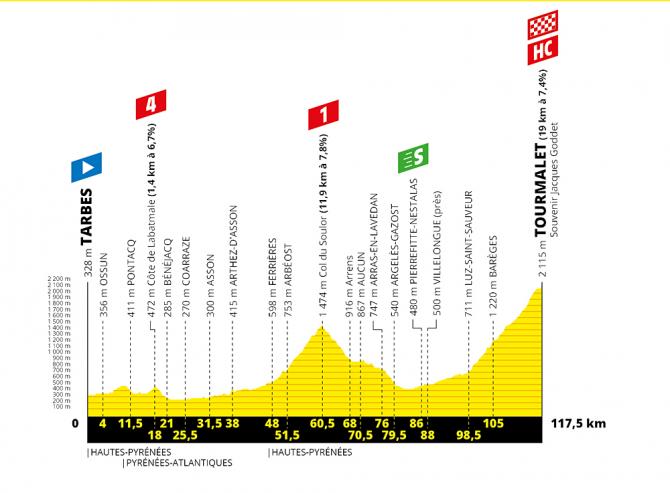

It's an interesting blend of the ancient and modern elements for the Tour's Pyrenean weekend, with, first up, a very short stage culminating in a summit finish on the Col du Tourmalet on Saturday.

To call the Tourmalet a part of the Tour's furniture would be a mistake; it's more like one of its foundations, a keystone of the race, virtually from the year dot. As the Tour's first HC climb in its history back in 1910, the Tourmalet ushered in the era of major mountain climbing.

The Tourmalet has rarely failed to figure since then, to the point where, with 82 ascents in the Tour in its back catalogue, the 19-kilometre climb has featured more than any other. And there have been some years, too, like in 1974 and 2010 – the years of the Tour's two previous summit finishes on the Tourmalet – when the race has gone over it not once but twice on consecutive stages.

Sunday's second summit finish in 24 hours, on Prat d'Albis, above the eastern Pyrenean city of Foix, meanwhile, is a total newcomer to the Tour. But in contrast to the modern-day trend for short, punchy mountain stages, the Tour's new Pyrenean climb on the block forms the culmination of a classic, long, rollercoaster stage along the mountain range, with a category-2 climb and three first-category ascents as the high points of four or five hours of relentlessly undulating roads.

Pessimistic fans predicting few fireworks this weekend can point to the fact that Thursday's incursion into the high mountains via the Peyresourde and the Hourquette d'Ancizan saw the GC battle flat-line completely.

But given the events in Friday's time trial, with Julian Alaphilippe (Deceuninck-QuickStep) remaining in yellow in dramatic style ahead of pre-race favourite Geraint Thomas (Team Ineos), there's widespread expectation that we should see some all-out attacks on the race's second visit to the Pyrenees.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

This would constitute a novelty of sorts. Whilst countless stages have gone over the Tourmalet in the past, the only two that have finished on the climb itself previously, in 1974 and 2010, resolved precious little except to confirm the status quo.

In 1974, the Tourmalet was the first of two stages won back-to-back by France's Jean-Pierre Danguillaume, salvaging local pride even whilst Eddy Merckx was cruising to a fifth Tour victory by a mere eight minutes and counting. Then, in 2010, Albert Contador and Andy Schleck, first and second overall in the classification, marked each other all the way to the summit. In fact, the decisive elements in that year's battle for victory turned out to be the time trial in Bordeaux a few days later, where Contador managed to retain his yellow jersey, and the results from an anti-doping lab in Germany a few weeks later, which proved to have the opposite effect.

However, the stakes are very different now. It feels much more likely this time around that after Friday's major GC battle in the Pau time trial, Alaphilippe will come under attack on Saturday from Team Ineos at the very least. As if that wasn't enough to light the fuse in the GC battle, this is the first time the Tour has gone above 2,000 metres this year, and is the most important of the mountain stages so far. So the Tourmalet may not decide the race, but it will certainly shape the overall outcome in a major way.

The ascent of the Tourmalet itself is so intimidating that it's a natural invitation to any self-respecting climber to go for it. First off on the stage, too, is the appetiser climb of the Col du Soulor, with its first-category summit roughly half-way through the 117-kilometre stage. It won't just be the front end of the peloton seeing action, either: combine the Soulor with the long, draggy approach of the Gorge de Luz valley and a large chunk of the peloton will surely sheer off and form a gruppetto even before the race reaches the definitive ascent of the Tourmalet. Although – and this could be an interesting sub-plot – on such a short stage, the time cut will be severely limited, and so the autobus cannot afford to take things too easily.

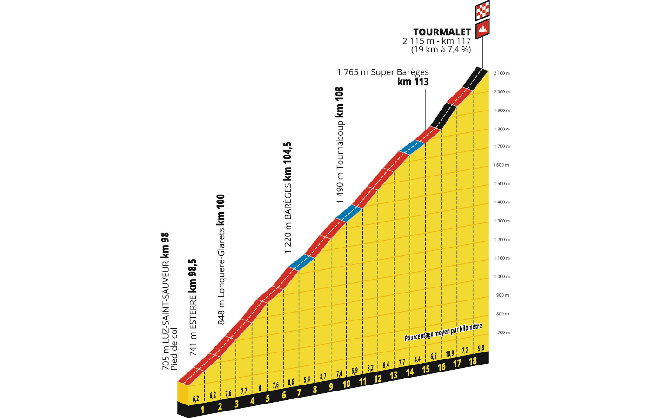

But it is the Tourmalet itself where the real battle of the day will likely unfold. From the town of Luz Saint Saveur at the foot of the climb to the Tourmalet's summit, the average gradient is 7.4 per cent, rising to an altitude of 2,115 metres. That's not the highest mountain pass of the Pyrenees by a long way – the Port d'Envalira on the Andorra frontier, which is the highest, tops out at 2,408 metres.

While the effects of altitude will only be felt in the last part of the climb, possibly the hardest thing about the Tourmalet to assimilate is that it has long, straight sections for much of the climb, most of it unchanging at around a leg-sapping six-to-eight per cent, which make it a very daunting affair psychologically as well as physically. Furthermore, there are sections where the gradient rises to above 10 per cent for a lengthy period, and two of them are in the final three kilometres – just when the riders will be at breaking point.

The other difficult section comes just after the village of Barèges, roughly half-way up the climb, and lasts for 1.5 kilometres at around 12 per cent. Climbers wanting to make a major impact on the ascent could well use this as a blasting-off point, rather than waiting for the finale and the late series of hairpins leading to the summit.

Much of the events of Sunday's much longer stage – 186.5 kilometres compared to 117.5 – will hinge on the outcome of Saturday. But it's easy to predict, even now, that a large, early break will set off on the westerly route out of Limoux, or at the latest start to stick on the second-category Col de Montségur after 60 kilometres.

The crunch elements of the stage, though, are its trio of first-category climbs at the end: the Port de Lers, the ultra-steep Mur de Péguère and the brand-new summit finish of Prat d'Albis. Hardest at its foot before easing out considerably towards the summit, this will be the last chance for an overall battle prior to the Alps. But with such a straightforward second part to the climb, the odds are that it will favour a fast uphill finisher of the ilk of Alejandro Valverde (Movistar) – or perhaps even Alaphilippe himself.

With the Alps yet to come, there is in theory plenty of time for the overall contenders to turn the tables again. But after such a high-powered opening first half of the race, there's too much at stake and too much to gain, still, to risk waiting until the third week – so expect fireworks on Saturday afternoon.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.