The crowning glory of the Tour de France Femmes - La Super Planche des Belles Filles

The final climb of the eight-day stage race which could deliver a dethroning blow or crowning glory

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The anticipation was high as the route of the Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift was announced back in October last year, with hopes that the course would provide a challenge that led to a worthy wearer of the yellow jersey on the long-awaited return of a women’s edition of the French Grand Tour. As the route from Paris to the Vosges mountains was revealed there was no question the feature that provided the crowning glory of the eight-stage race was the La Super Planche des Belles Filles.

It may not be a climb that resonates in Tour de France folklore quite as loudly as the Alpe d’Huez, Tourmalet or Ventoux but it has an exciting, if more recent, history nevertheless. Additionally, the terrain it presents to riders as they bring 1,029 kilometres of racing from Paris to the Vosges mountains to a close means Sunday should surely add another unforgettable chapter.

Anything could happen on La Super Planche des Belles Filles, the final seven kilometre test of the 2022 Tour de France Femmes, which saves the hardest part for the dying stages with two brutal stings – gravel and gradient.

The “Super” part of the climb extends onto an unpaved surface and a brutally steep finishing ramp. It is a test that will leave no room for doubt that the rider who climbs onto that final podium at the top of the summit and into the yellow jersey will have earnt her prize and place in history.

Heading into the stage Annemiek van Vleuten (Movistar) is in prime position, after a long-range attack on stage 7, with Demi Vollering (SD Worx) going along for part of the ride. Van Vleuten is now in yellow with a 3:14 lead on Vollering and 4:33 on Kasia Niewiadoma (Canyon-SRAM), though stage 8 will present every opportunity for GC challengers to exploit any weakness or mishap, with two categorised ascents to set the scene before the crowning climb.

Cyclingnews takes a closer look at the ascent which has the potential to flip the GC order right at the very last moment.

The history of the climb

Although not so well known, the tales of battles on the fabled slopes of the legendary mountains so many cycling fans know from the Tour de France also exist within the women's peloton.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

A women’s edition of the race ran from 1984 to 1989 alongside the men’s race, with the rider from United States Marianne Martin going down in the history books as the first winner after 1,059km across 18 stages, which took in the Alps and Pyrenees.

Then came the events that, although not officially a women’s Tour de France, incorporated key climbs associated with the men’s race. There was the Tour Cycliste Féminin from 1992-1997, where Fabiana Luperini in 1996 crashed yet when her teammates brought her back to the peloton sore and bleeding at the base of the Tourmalet, she still managed to fight on and win at the top to pull on the yellow jersey. Then from 1998-2009, there was the Grande Boucle Féminine Internationale, where in 2006 Nicole Cooke went on a solo raid on Mount Ventoux to clinch the title.

However, La Super Planche des Belles Filles was introduced to the Tour de France in the years when there were no comparable women’s race, so 2022 will be the year the women will start building their stories of the climb. The history of the men’s race on the slopes of the mountain, however, will provide a frame of reference.

“People will understand what we are doing when we can say that we finish on La Planche des Belles Filles,” said Annemiek van Vleuten (Movistar) in a Cyclingnews blog after the route announcement. “So many fans have watched it during the previous editions of the men's Tour de France, so they know it's a hard climb.”

The Planche des Belles Filles was introduced to the Tour de France in 2012 on stage 7, providing the first mountaintop finish of that year’s Tour. It was at that stage that the then-young British rider Chris Froome took the victory and drew the admiration of defending champion Cadel Evans: "Froome was incredible - he rode the front the last 3km or something and he was able to follow me and accelerate past me."

It’s next appearance was in 2014 on stage 10, reshuffling the GC as Vincenzo Nibali reigned supreme on the climb and stepping into the yellow jersey which he also donned on the Champs-Élysées. In 2017 it was back on stage 5, with Fabio Aru springing clear of the GC group 2km from the summit and taking victory while Chris Froome this time came in third and stepped into the yellow jersey, which he also finished with on stage 21.

By 2019 the climb had been used often enough to become familiar, but then there was an extra twist. This was the year the Planche des Belles Filles became La Super Planche des Belles Filles. Organisers added an extra section at the top, taking the finish line beyond the paved road and onto an unpaved dusty surface and steep section beyond. At the front as the tarmac turned to gravel, two riders with more than a minute clear battled for the stage victory, with Dylan Teuns beating Giulio Ciccone to the line. Further back among the GC rivals the battle was running hot with Romain Bardet slipping out the back and Geraint Thomas besting the two Frenchmen, Thibaut Pinot and Julian Alaphillipe, who gave the yellow jersey up to Ciccone that day.

The Planche des Belles Filles joined the race again in another form in 2020, providing the finale of the 36 kilometre time trial where Tadej Pogačar overhauled Primož Roglič, taking almost two minutes on his compatriot and the yellow jersey when it counted most.

Freshening the memories of the climb, it also made its sixth appearance in the men’s edition of the race in 2022, providing the first summit finish on stage 7 and a battle between two riders who were head and shoulders above the rest. Here Pogačar reeled in an attack by Jonas Vingegaard (Jumbo-Visma), reinforcing his favourite status by reigning supreme on the climb which had been such a crucial part of his journey to take yellow two years ago.

However, this was but the first summit finish of the race so while Pogačar had yellow at the end of the day Vingegaard did not have to wait long for his next chance to take the race lead, which he then kept all the way to Paris. The women, on the other hand, after cresting La Super Planche des Belles Filles will have a far more final outcome, with the next chance in the chase for yellow having to wait a whole year.

Location

The Planche des Belles Filles is situated in the Vosges mountains in the east of France, close to the intersection of the French, German and Swiss borders and located between Strasbourg and Besançon.

The position of the lower range of mountains means that it has often provided the first summit finish of the Tour, delivering an entree before the Alps and Pyrenees. However, it became a final stop before Paris in 2020, when it was home to a pivotal time trial.

For the Tour de France Femmes, it provides a mountainous finale comfortably within reach of Paris for the eight-stage event which started at the Eiffel Tower on July 24, the same day the Tour de France ended.

The climb

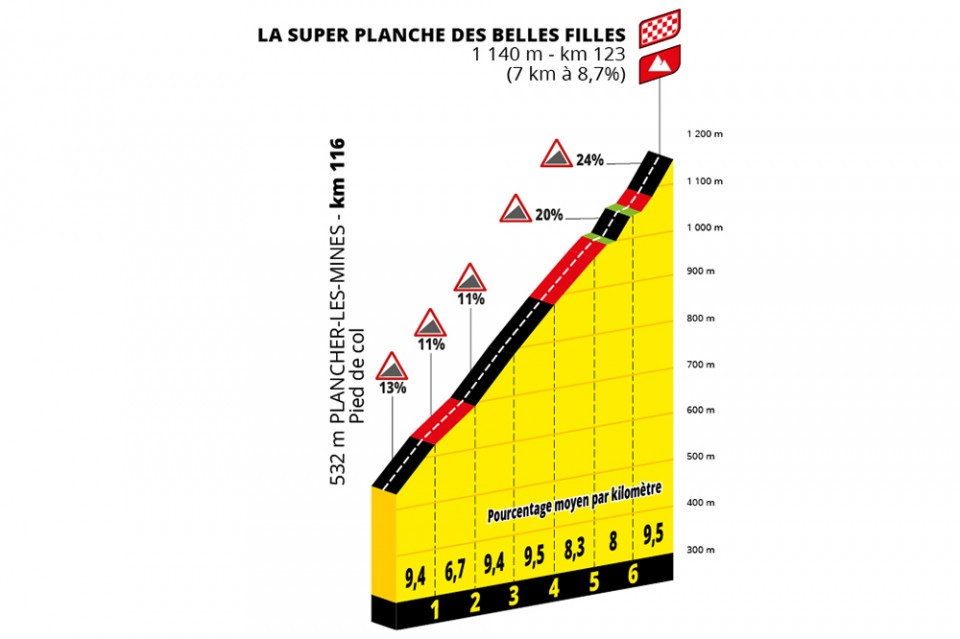

The Vosges mountains may not reach the heights of the Alps of the Pyrenees but there should be no underestimating La Super Planches des Belles Filles, which stands at 1,140 metres above sea level. Coming at the end of eight tough days in the saddle – and with the category 2 Côte d'Esmoulières and the tough category 1 Ballon d’Alsace already in their legs from earlier in the 123km stage – the seven-kilometre finishing climb serves an average gradient of 8.7%.

There is no easing into the final category 1 climb as the first kilometre of the tree-lined road zig zags its way up the mountain and delivers an average gradient of 9.4%. The climb then peaks at 13% before a slight reprieve in the second kilometre, if you can call an average gradient of 6.7% a reprieve. There is even a small flattish section, and what looks like a momentary dip, before the gradient then picks up again through the next two kilometres back to an average of 9.4% and 9.5%.

Back to 8.3% for kilometre five of the climb, and then an average gradient of 8% for what would be the run into the finish line if the climb hadn’t been stretched onto the gravel. It is far from an even 8% though, with a couple of flat ramps sandwiching a section with pitches of up to 20%.

That final section doesn’t look that ridiculously steep at the beginning but the start isn’t an indicator of what is to come. The dust and loose surface of a few hundred metres of unpaved road adds one layer of drama and then the gradients of the final paved section that the riders turn onto with around 300 metres to go adds another.

The finish line may be ever so close, but with the gradient peaking at 24% in those final brutal metres of the eight-stage race it may, for some riders, feel like an eternity.

“It’s a killer,” said Demi Vollering of the climb after doing a reconnaissance ride in the months before the Tour de France Femmes. “There are not so much tactics anymore, it is just the strongest rider who comes first on top here.”

Simone is a degree-qualified journalist that has accumulated decades of wide-ranging experience while working across a variety of leading media organisations. She joined Cyclingnews as a Production Editor at the start of the 2021 season and has now moved into the role of Australia Editor. Previously she worked as a freelance writer, Australian Editor at Ella CyclingTips and as a correspondent for Reuters and Bloomberg. Cycling was initially purely a leisure pursuit for Simone, who started out as a business journalist, but in 2015 her career focus also shifted to the sport.