Tour de France 2021: 5 key stages

An in-depth look at the critical junctures of the yellow jersey battle

The 2021 Tour de France has a classic look to it, its first week featuring several stages for the sprinters as well as an individual time trial, the final week packed with challenging mountain tests in the Pyrenees that will sort out the contenders for the yellow jersey, which will be decided in a second time trial on the penultimate day.

With the start of the race in Brest now under a week away, we analyse the five most critical stages in the GC battle.

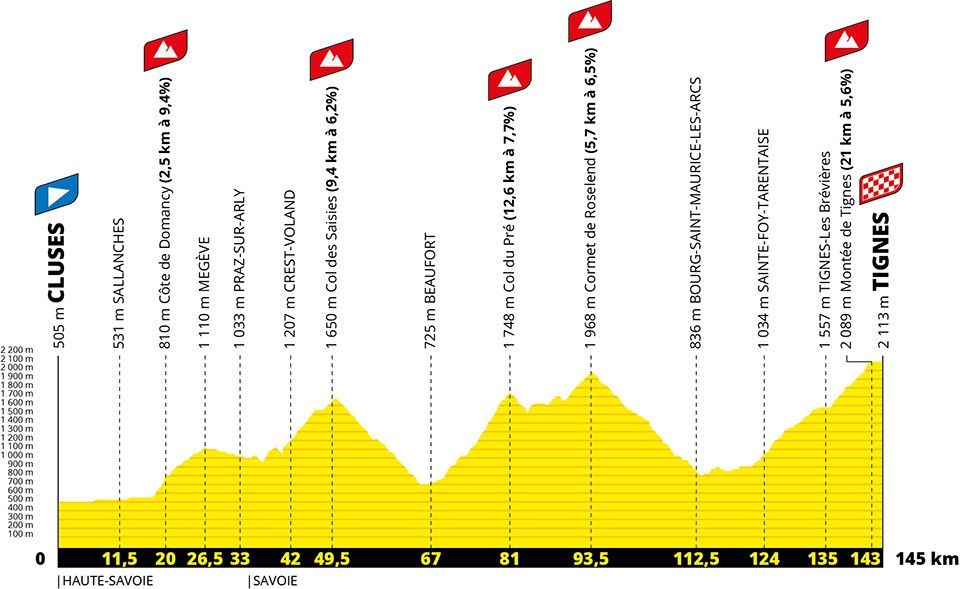

Stage 9: Cluses – Tignes, 145km

Unlike this year's race, which sought out the high mountains right from the start, the 2021 edition has a much more traditional parcours. During the opening week, there are stages that will favour the puncheurs, four that will suit the sprinters, and the first of two mid-length time trials.

Speaking during the presentation of the route on French TV’s Stade 2, Tour de France director Christian Prudhomme evoked the possibility of the elements, and particularly the wind, being a complicating factor, especially on the four stages that comprise the Breton Grand Départ. However, as the opening week of the 2018 race showed, if the wind doesn’t blow, these stages could be quite dull with regard to the GC battle.

This should change, though, when the race reaches the Alps, where there are two punchy stages on the menu. The second of them, on the eve of the first rest day, looks particularly testing, with five climbs crammed into 145km, the final one to the first of the Tour’s three summit finishes.

The first climbing test is the Côte de Domancy, the foundation of Bernard Hinault's legendary World Championship success in 1980. The next is the Col des Saisies, which is followed by a long drop to Beaufort, and consecutive ascents, first to the Col du Pré and, soon after, to the beautiful Cormet de Roselend. After another long descent, to Bourg-Saint-Maurice, the riders will start the 21-kilometre ascent to Tignes, which missed out on its stage finish in 2019 due to landslides during a violent mountain storm.

The critical section of this long ascent arrives at the village of Les Brevières, where the road rears up steeply to climb the rockface next to the Chevril dam for two kilometres. Reaching the top of the dam, the road rises much more steadily for another 7km to the line, but altitude could tug at the resources of some of the GC contenders, the finish standing at 2,113 metres.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Stage 11: Sorgues – Malaucène, 199km

Mont Ventoux returns to the Tour route for the first time since 2016, when a fearsome Mistral wind barrelling across 'the bald mountain' forced the shortening of the stage and, ultimately, saw race leader Chris Froome running towards the finish after his bike had been damaged in a collision with a motorbike.

Prudhomme and Tour route director Thierry Gouvenou have decided against a summit finish, this decision partly down to a realisation that these high-altitude finales can often neutralise the racing between the GC contenders until the final few kilometres. But the pair also wanted to serve up a Ventoux stage with a difference, and they’ve achieved that objective by proposing the first-ever double ascent of this iconic and infamous peak.

Beginning in Sorgues, just to the north of Avignon, the stage tracks eastwards to Apt, turning northwards there to Saint-Saturnin-lès-Apt and the 9.3km ascent of the Col de la Liguière. Beyond it is the small town of Sault, the start of the longest but by far the easiest of the three roads accessing the top of the Ventoux. Winding through forest, the gradient barely touches 6 per cent over the 18km to Chalet Reynard, where the road meets the much steeper one coming up from Bédoin.

The gradient is much more severe over the final 6km to the summit, from which the riders will drop down the western flank of the mountain. Passing the little ski resort of Mont Serein, where Cadel Evans won a rare stage to climb from the west during the 2008 edition of Paris-Nice, this descent is extremely fast. 1966 Tour winner Lucien Aimar has said the police motorbike following him down this road in the 1967 clocked 140km/h on one section.

After passing through the finish in Malaucène for the first time, the route bumps around the base of the Ventoux to reach Bédoin for the classic ascent, which averages close to 9 per cent for 15.7km. Reaching the summit, the riders will, for the first time since 1994, continue down the rapid descent into Malaucène once again to finish.

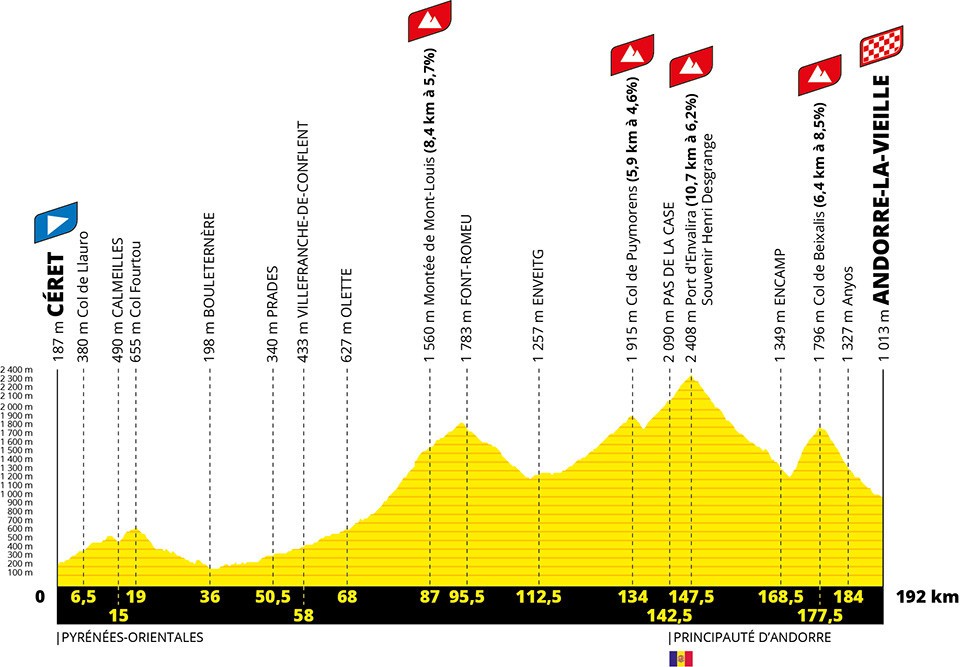

Stage 15: Céret – Andorra la Vella, 192km

As the Tour moves westwards across southern France from the Alps to the Pyrenees, the wind could very well come into play on the stage between Nîmes and Carcassonne. Two days on from that intriguing test, the battle to decide the yellow jersey in the Pyrenees will intensify as the race heads for the mountain principality of Andorra, its only departure from France during the 2021 edition.

The first three-quarters of the stage takes place in Pyrénées-Orientales, initially bumping through oak-clad hills from the Tech valley to the Têt and then climbing steadily through the Catalan Pyrenees Regional Park to the Montée de Mont-Louis, beyond which the road continues to rise to Font-Romeu, the site of France’s elite high-altitude training centre. From there, the route descends right to the Spanish border, then turns north-west towards the Col de Puymorens.

This pass is the stepping stone to the 'roof' of the Tour, the riders dropping briefly away from it and then climbing again into Andorra and up to the Port d’Envalira, which tops out at 2,408m. A long, sometimes fast, but mostly straightforward descent will take the race into the heart of the little mountain territory, for the final test, the Collada de Beixalis.

Many of the riders in the bunch will know this climb well from training rides around their homes in Andorra, and many others will have tackled it in the Vuelta a España, most recently in 2018, when it featured twice on the penultimate stage, when Simon Yates sealed overall victory. At 6.4km, it’s not very long. It is, though, very irregular, with some very steep ramps that will provide the best climbers with a launch-pad for attacks.

The descent is technical initially as the road zigzags down to Anyós, then straighter and very fast on the final drop into the finish in the country’s capital, Andorra la Vella, where the group of GC favourites is likely to have been slimmed down to include just those with a realistic chance of victory in Paris.

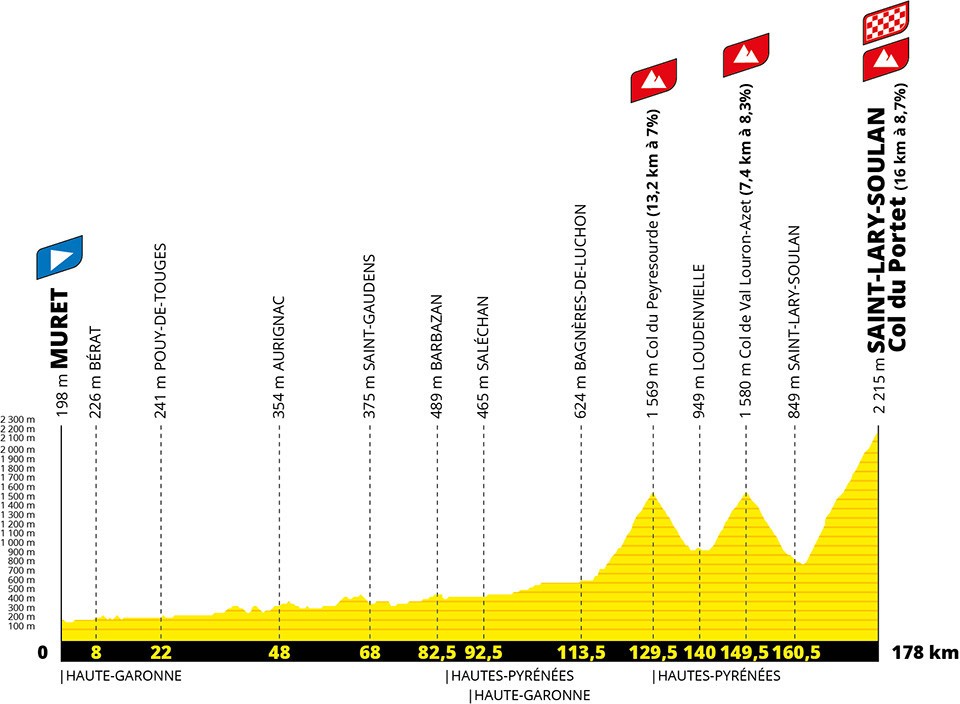

Stage 17: Muret – Saint-Lary-Soulan Col du Portet, 178km

Bastille Day brings the return of the Col du Portet, first tackled in 2018 at the end of a 65km stage that began with the riders on an F1-style grid, Nairo Quintana the eventual victor as Geraint Thomas tightened his grip on the yellow jersey.

The day gets under way in Muret, just to the south of Toulouse, the riders staying in the valleys for more than 100km until Bagnères-de-Luchon, the start town for that short 2018 stage. The recreation of that day begins with the ascent of the Col de Peyresourde, where Tadej Pogačar recouped some of the ground that he had lost to his GC rivals in the cross-winds the day before in this year’s race. As on that stage, which was won by AG2R La Mondiale's Nans Peters, the riders will drop rapidly from the Peyresourde into the lakeside town of Loudenvielle and, not far beyond, the opening ramps of the Col d’Azet.

Although little more than half the length of the Peyresourde, the Azet is a good deal steeper, averaging 8.3 per cent as it rises through thick woodland initially to reach open pasture higher up, close to the small Val Louron ski station. Another fast and sometimes technical descent follows to reach Saint-Lary-Soulan.

The riders will barely have time to catch breath before they’re climbing again, this time on the final test, by some distance the toughest of the day’s trio of mountains. Averaging 8.7 per cent for 16km, the climb to the Portet comes in two halves, both almost incessantly unrelenting in their difficulty. The first of them ascends to Espiaube, the gradient averaging more than 9 per cent and significantly above that on the long, straight rise from the valley floor to the first hairpin, where a plaque marks the point where Raymond Poulidor attacked and dropped Eddy Merckx on his way to victory at Pla d’Adet in the 1974 Tour.

At Espiaube, rather than kicking left to that ski resort, the riders will veer right towards the Portet, reaching its opening pitches very soon after. Weaving frenetically, the gradient changes constantly, sometimes dropping briefly to 5 per cent, the slope then jagging up to three times that figure the next moment. It’s almost impossible to maintain a rhythm, making it ideal terrain for pure climbers like Quintana and Dan Martin, the runner-up to the Colombian in 2018. As it turns to run more directly towards the summit, the road climbs to and then well above 2,000 metres, the gaps likely to be substantial between the favourites at this the second of the three high-altitude finishes.

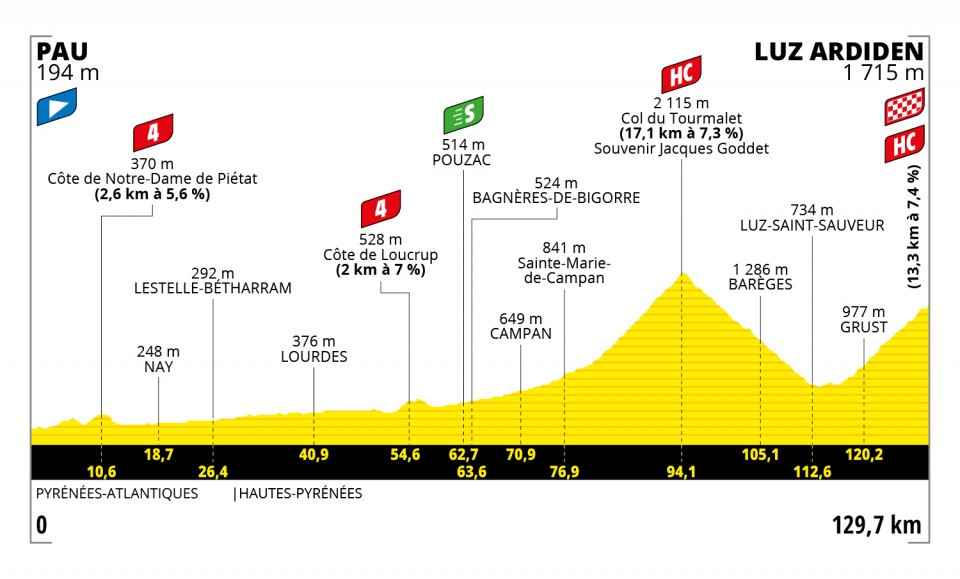

Stage 18: Pau – Luz Ardiden, 130km

The day after the second summit finish on the Col du Portet comes the third, the Tour returning to Luz-Ardiden for the first time since 2011, when Samuel Sánchez won a stage that is best remembered for Thomas Voeckler's courageous defence of the yellow jersey. Like the Portet stage, this one commences with a long run through the valleys from the start in Pau to reach Sainte-Marie-de-Campan, at the foot of the eastern flank of the Col du Tourmalet.

Averaging 7.3 per cent for 17.1km, this is arguably – although it’s very hotly debated – the easier side of the Tour’s favourite pass, the gradient negligible for the first handful of kilometres. However, above Artigues, with 10km remaining to the top, the climb bares its teeth, the road steepening on the approach to La Mongie, then even more as it clambers through the ski resort to reach the final few kilometres up to the famous summit.

The descent is fast on a well-surfaced and, for the most part, wide road that will send the riders hurtling down through Barèges to Luz-Saint-Sauveur in the valley bottom. A short, sharp ramp will lead them to the spectacular span of the Pont Napoléon and, moments later, the start of the final climb.

A little like the Tourmalet, the ascent to Luz-Ardiden begins comparatively tamely. Yet, after a couple of kilometres it begins to ascend more steeply, particularly as it passes through the picture-postcard village of Grust, where an extended stretch of hairpins begins. In a similar way to Alpe d’Huez, these are very flat on the apex of the corners and the ramps between them are steep, which can break the rhythm of grimpeurs-rouleurs such as Geraint Thomas and Tom Dumoulin and, as a result, give the pure climbers a useful edge.

Emerging above the tree line, the huge banks between the switchbacks make for a spectacular natural arena, with fans able to see a considerable distance down the climb, which tops out next to the ski station at 1,720m. Taking into account the accumulated fatigue and the amount and difficulty of the climbing in the second half of this stage, the gaps between the favourites should be significant.

Peter Cossins has written about professional cycling since 1993 and is a contributing editor to Procycling. He is the author of The Monuments: The Grit and the Glory of Cycling's Greatest One-Day Races (Bloomsbury, March 2014) and has translated Christophe Bassons' autobiography, A Clean Break (Bloomsbury, July 2014).