Tour de France 2018: Five key stages - Video

Cobbles, shortened mountain stages and pivotal time trial

This article is sponsored by Eurosport Player.

Dumoulin: It's not my motivation just to challenge Froome - Podcast

Tour de France 2018 route revealed

Chris Froome: Tour de France could be torn to pieces in first week

2018 Tour de France route suits me more than this year, says Bardet

2018 Tour de France route in 3D - Video

2018 Tour de France route analysis with Bardet, Yates and Froome - Podcast

In the not so distant past, Tour de France routes seemed to follow a set template, with a flat opening week followed by a long time trial and two blocks of mountains stages, before a late stage against the clock wrapped things up neatly before the final promenade in Paris. Year on year, the towns on the road book changed but the tenor of the race remained the same.

Since Christian Prudhomme took over as race director 10 years ago, however, the Tour de France has increasingly railed against such predictability. In the Indurain and Armstrong years, save for crashes or incident, the battle for the yellow jersey often felt limited to just a few set-piece mountain stages or time trials. In the modern Tour, by contrast, the aim of the route planners seems to be to extend the GC battle across almost every day of the three weeks.

That doesn’t always materialise, of course – witness the détente that reigned during the flat stages in week two this year – but the 2018 Tour de France route, presented in Paris on Tuesday, continues the recent trend of blending traditional stages with some striking innovations in a bid to keep the overall contenders guessing.

There are potential perils on just about every stage of the 2018 Tour, but at this early juncture, these five days in particular stand out.

Follow it all live and uninterrupted on Eurosport player. Find out more here.

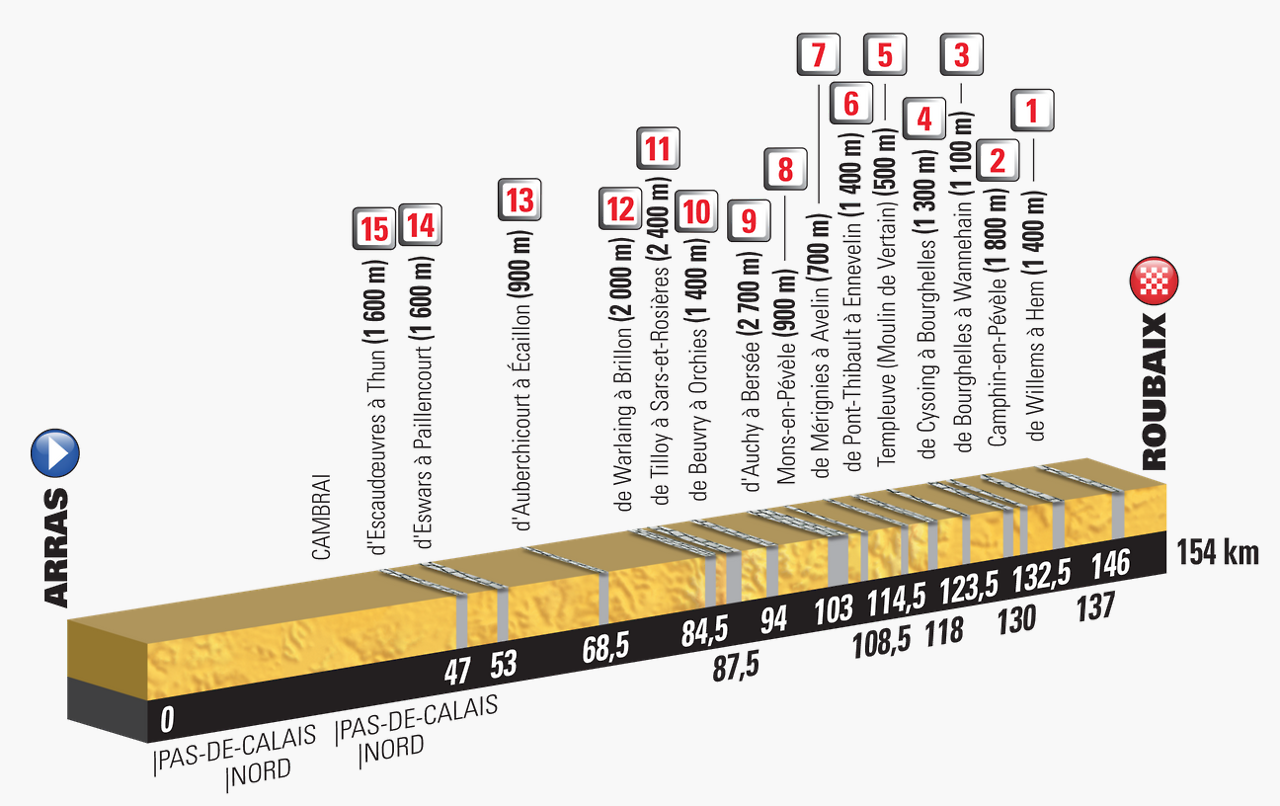

Stage 9, July 15: Arras Citadelle – Roubaix, 156.5km

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“I don’t understand why they’ve put in the cobbles,” Eusebio Unzue lamented after the lights went up in the Palais des Congrès on Tuesday morning.

A clue lay in Christian Prudhomme’s speech: on three separate occasions, the race director referred proudly to the Tour’s television figures. The Tour organisation has long looked to maximise that television audience by populating the race’s weekends with time trials and mountain stages. The geography of this year’s parcours meant that something different would be required to draw the casual viewer away from the build-up to the World Cup final that evening or from the men’s singles final at Wimbledon that afternoon.

Instead of the more routine stage Unzue might have preferred, the Tour peloton faces what promises to be its most sustained examination on the cobbles since back-to-back legs across the pavé brought a premature halt to Bernard Hinault’s race in 1980. After tackling 13.2 kilometres of cobbles in 2010, 15.4 kilometres in 2014 and 13 kilometres in 2015, next July’s offering features no fewer than 15 sectors of pavé for a total of 21.7 kilometres. Whereas the recent forays onto the cobbles were crammed into the final part of the stage, this stage is less a taste of Paris-Roubaix than a miniature version of the Queen of the Classics.

The first cobbled section comes after just 47 kilometres at Escaudoeuvres, and although there is a respite of sorts midway through the stage, the final 70 kilometres includes a dozen sectors of cobblestones. There are some very familiar passages on the rocky road to Roubaix – Orchies, Mons-en-Pevele, Ennevelin and Templeuve all feature – and, as at Paris-Roubaix itself, the staccato rhythm of pavé in the final two hours of racing leaves little margin for error. Those caught behind through ill-fortune or poor bike handling will struggle to recoup the ground, and the time gaps could be very significant indeed.

More than on any other stage of this Tour, the weather conditions will have an enormous bearing on the outcome. Traditionally, the Tour’s treks across the cobbles have ended at least one contender’s challenge – Iban Mayo in 2004, for instance, or Frank Schleck in 2010. The heavy rainfall in 2014 contributed to a chaotic day’s racing that saw maillot jaune Vincenzo Nibali make a hefty down payment on final overall victory.

Twelve months later, the expectation was that the pavé would prove equally decisive, but on dry roads, there were few scares as the podium contenders broke even. Viewing figures, mind, remained solid.

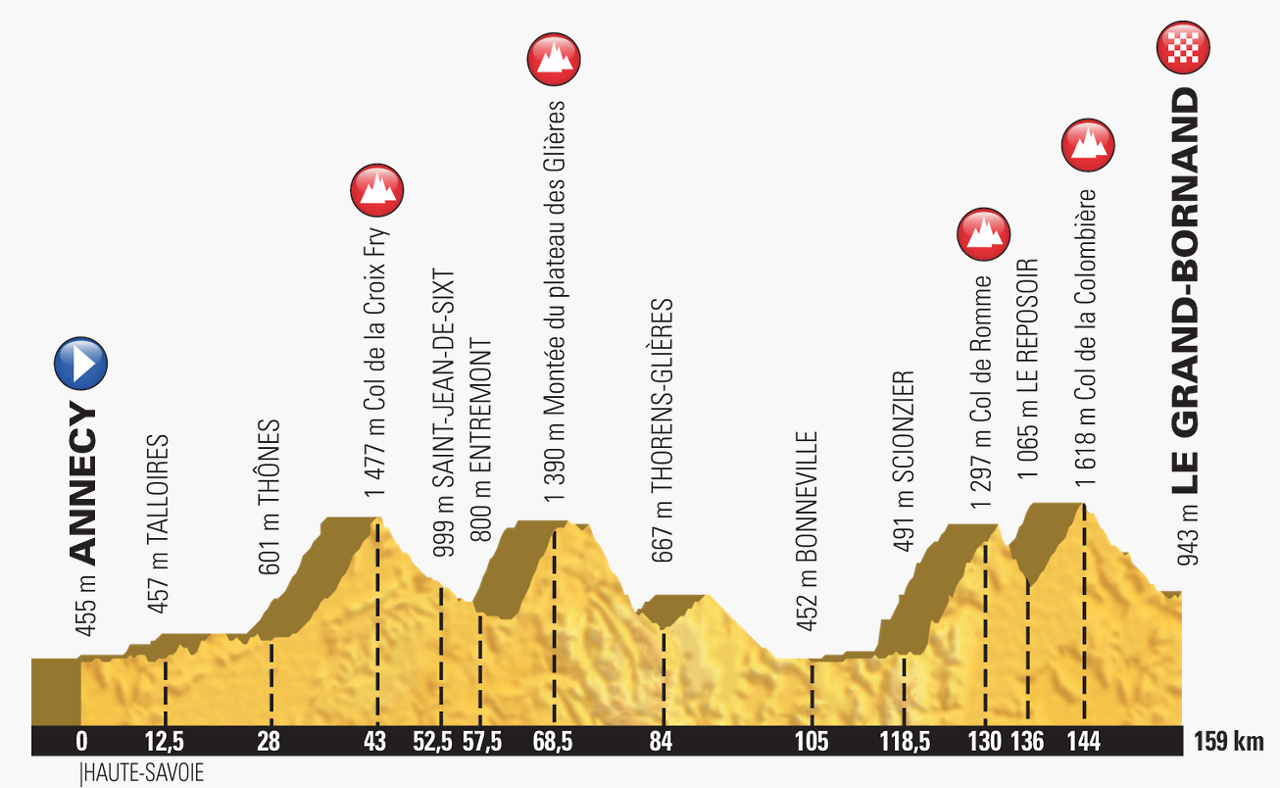

Stage 10, July 17: Annecy – Le Grand Bornand, 158.5km

The first week of every Tour de France is rife with possible pitfalls, and with a team time trial, some early frissons in Brittany, a trek across the windswept north and a healthy smattering of cobbles, the 2018 hits its quota and then some.

And yet, regardless of the time gaps come the first rest day in Annecy, it will be hard to shake off the feeling that the Tour only truly begins when it enters the mountains on stage 10 to Le Grand Bornand. It will certainly be a different kind of race from that point on.

“This is the stage where the leaders risk losing the most,” the Tour’s technical director Thierry Gouvenou said on Tuesday. “Some of them won’t have dealt well with the first 10 days on the flat, and the transition to the mountains could be brutal.”

The Tour’s stint in the Alps begins with the ascent of the Col de la Croix Fry, followed in turn by the new climb of the Montée du Plateau des Glières, where Julian Alaphilippe won at the 2013 Tour de l’Avenir. As well as delivering an early test of legs (6km at an average gradient of 11%), Plateau des Glières also provide a test of nerve, with its two-kilometre stretch of unmade road over the summit.

Coming some 90 kilometres from the finish, however, the Glières ought to be primarily a scenic prelude to the demanding, two-part finale to the stage, as the peloton tackles the Col de Romme and the Col de la Colombiere in quick succession ahead of the drop to the finish at Le Grand-Bornand. It is a combination that last featured in 2009, when Frank Schleck claimed stage victory.

There are more demanding mountain stages to come later in the race, but this first leg at altitude should, as ever, provide some firm pointers as to who will and will not win the Tour. It also set the tone for what is to follow tactically.

For five of the last six Tours, Team Sky have stifled the race with their tempo riding in the mountains and disarming strength in depth. It would be a surprise to see any change in their playbook here; it remains to be seen what Froome’s rivals can conjure up.

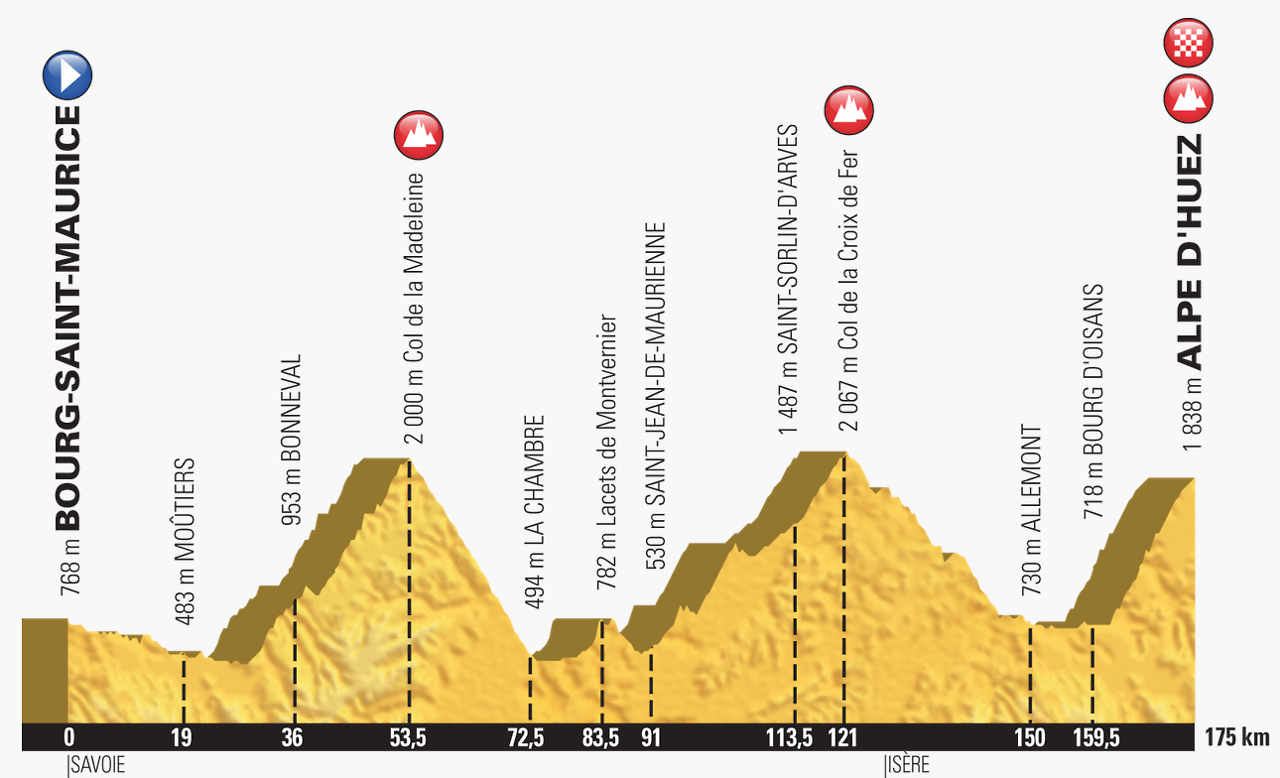

Stage 12, July 19: Bourg-Saint-Maurice Les Arcs – Alpe d’Huez, 175.5km

Sometimes old friends are best. ASO have charted a rather daring route in many respects, but few stages whet the appetite quite like this Alpine classic, which brings the Tour over the Col de la Madeleine and Col de la Croix de Fer en route to a very familiar summit finish at Alpe d’Huez.

The return of the Alpe after a three-year hiatus was a certainty, but there were all sorts of rumours flying around about how it would be approached. In the end, Prudhomme and Gouvenou have opted for a straightforward approach. No alarms and no surprises, just nigh on 5000 metres of climbing in a little over 100 miles of racing.

Froome didn’t hesitate in labelling it the queen stage of the 2018 Tour, while Romain Bardet murmured his approval for what he termed a 'marathon' stage. “Stages like that are part of the legend of the Tour, and they add another, historical dimension to the race,” Bardet said.

The mightiest mountains of the Tour often inhibit as much as they inspire, however. The sheer length of the Madeleine and Croix de Fer combination means that the stage is likely to be one of attrition rather than of attacking, at least among the podium contenders. It is precisely the kind of stage where Team Sky – despite being reduced to eight riders – could have the manpower to dictate terms all the way to the Alpe, while the severity of that last ascent means that their rivals might well be minded to leave them to it until the final haul to the finish.

That said, the cumulative fatigue of such a demanding stage will surely make itself felt on the 21 hairpin bends from Bourg d’Oisans to the finish at Alpe d’Huez.

It is also a climb that has proved something of a conundrum for Froome, who endured his most trying afternoons of the 2013 and 2015 Tours on its slopes. A rider like Vincenzo Nibali, who tends to endure these ‘marathon’ days better than most, will look to punish any lapses.

Stage 17, July 25: Bagnères-de-Luchon – Saint-Lary-Soulan (Col de Portet), 65km

From a marathon to a sprint, though it’s worth noting that the Tour de France has featured a shorter and more explosive mountain stage in the past.

Back in 1972, the peloton peloton lined up for a 28-kilometre stage (21 kilometres of total climbing) from Aix-les-Bains to Le Revard, where Cyrille Guimard out-sprinted Eddy Merckx to take stage honours. If that leg amounted to a massed start hill climb, however, this short but vicious offering threatens to be something of a miniature epic.

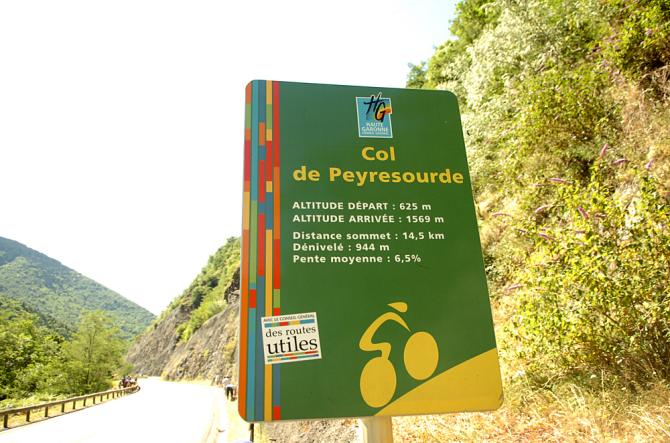

Every rider in the peloton will be warming up on the turbo trainer in Bagnères-de-Luchon before the start. Once the flag drops, the peloton will tackle the Col de Peyresourde, reaching the summit after 15 kilometres. Following a rapid descent to Loudenvielle, the road climbs again with the 10-kilometre ascent of the Col de Val Louron-Azet. Another quick drop to Saint-Lary-Soulan follows before the demanding final haul up the Col de Portet, where the finish line is situated some 2215 metres above sea level. The climb is 16 kilometres in length at an average gradient of 8.7 per cent, tough enough for Prudhomme to liken it to the Tourmalet, and all told, some 38 kilometres of the stage are uphill.

Prudhomme has admitted that a large part of the rationale for incorporating such a variety stage types and distances on the 2018 Tour was to try to prevent any one team from dominating proceedings, but it would be remiss to suggest the concept of the short mountain stage was an attempt at Team Sky-proofing the race. The modern Tour’s fascination with limited distance mountain stages predates Froome’s late emergence as a Tour contender and Team Sky’s status as a preeminent stage racing team.

The idea took root back in 2011, when Alberto Contador blew the race apart on the short and sharp leg to Alpe d’Huez. It was the afternoon Thomas Voeckler lost yellow, Andy Schleck took over the race lead, Cadel Evans saved his Tour and Pierre Rolland won atop Alpe d’Huez. It all took place in a little over three hours, and every minute was broadcast live. It was, in other words, made for television.

Stage 20, July 28: Saint-Pée-sur-Nivelle – Espelette (ITT), 31km

Some kilometres are more equal than others. The Tour’s diet of time trialling has been heavily restricted in recent years, but such rationing has served only to amplify the importance of each mile raced against the clock. The 2017 Tour route was heralded beforehand as one of the most open in recent memory, but instead Team Sky held Froome’s rivals at arm’s length and the Briton essentially made the difference in the short time trials that bookended the race.

Despite its many innovations, the 2018 Tour de France might yet provide a very similar kind of race. For all the dangers of the opening week, the 35-kilometre team time trial on stage 3 is the stage most likely to separate the overall contenders. For all the metres climbed in weeks two and three, the penultimate stage in the Basque Country is likely to produce the biggest time gaps.

This final test will surely weigh on the minds of men like Romain Bardet. The Frenchman could hardly have asked for a more amenable Tour route than this year’s, but although he more than held his own against Froome in the mountains, all of that work was undone in the sobering final time trial in Marseille. Bardet rolled down the start ramp ostensibly within striking distance of Froome’s yellow jersey. He reached the finish 22 kilometres later scrambling to defend a podium spot from one of Froome’s domestiques, losing 1:57 to the Briton in just 28 minutes of racing.

Bardet, Quintana and others will need to carry yellow and a sizeable buffer into this final test if they are to win the 2018 Tour de France, especially if the chasing pack includes one or all of Froome, Richie Porte and Tom Dumoulin.

Although the hilly course is ostensibly weighted to give the climbers a fighting chance, none of the marquee time triallists should be unduly discommoded by the steep Côte de Pinodieta (900 metres at 10.2 per cent) in the finale. Dumoulin was utterly dominant, after all, on the final ascent up Mount Fløyen at the recent Worlds time trial in Bergen, where he almost caught Froome for two minutes in the finale.

Indeed, the likely participation of Dumoulin at the 2018 Tour de France provides Froome and Team Sky with the kind of challenger they have not yet faced during their years of dominance – a demonstrably superior time triallist. His very presence, more than the novel route, might yet inspire the biggest change in tactical approach from the GC contenders.

Follow it all live and uninterrupted on Eurosport player. Find out more here.