Tom Pidcock: In the Cross Fire

British talent writes about his relationship with cyclo-cross in an excerpt from The Road Book

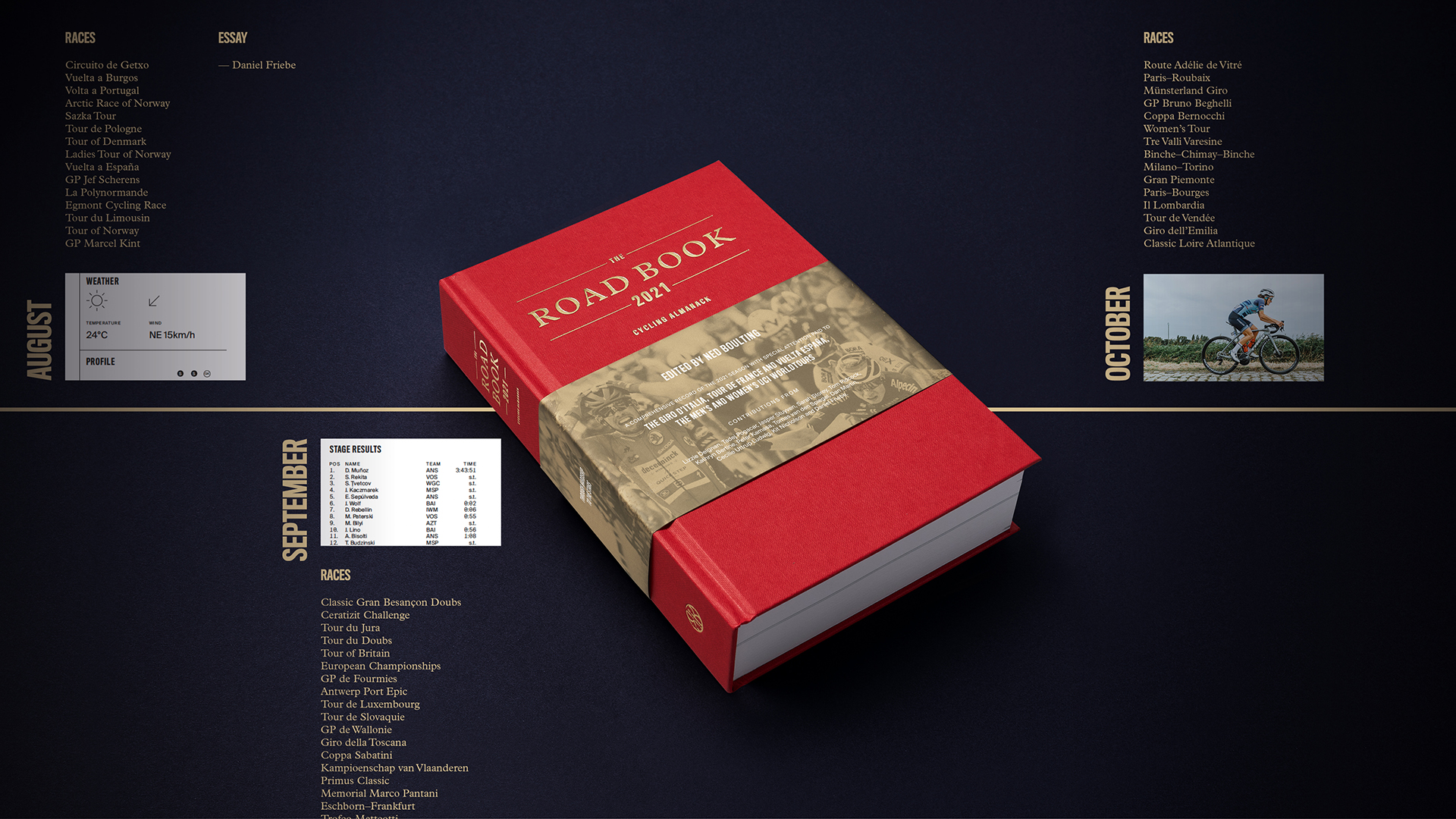

The following excerpt is written by Tom Pidcock (Ineos Grenadiers) and is featured in the 2021 edition of The Road Book – available to buy now.

The Road Book features nearly 900 pages packed with race reports, statistics, team profiles, infographics, trivia, and photography from the 2021 season. In addition, exclusive accounts from cycling’s biggest stars, including Tour de France and Paris-Roubaix winners Tadej Pogacar and Lizzie Deignan, sit alongside contributions from the cream of cycling writers and journalists.

Cyclingnews and the team behind The Road Book have teamed up to create a fantastic offer that includes free delivery for all UK-based purchases and a huge discount for all ROW territories. Each purchase made through Cyclingnews also includes four exclusive A5 prints, which you can see in the gallery below. For more details click here.

Cyclo-cross started off for me as a bit of fun, really. I was already on the British Cycling Junior Academy, concentrating on track and road, and I was just doing cross as a little bit of something extra. So there was no pressure. I was only doing it for fun.

The first cross race I did abroad was the European Championships. I went away with the GB team on the boat overnight. It was like going away on a school trip almost. It was a sandy course and I only had mud tyres, so I wasn’t very well equipped for it. But I started from the back of the grid and ended up finishing eighth.

Everybody told me, ‘Bloody hell! That’s amazing!’ But all I’d done was finish eighth.

‘What do you mean?’ I asked them.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

‘Well, no British rider’s ever really done that before.’

So I thought, ‘OK. That’s cool.’ And that was it.

In 2016 I went to my first World Championships in Zolder as a first-year junior. I had a really strong race even though I had started from the back, but I’d thought to myself that I could definitely come back the following year and win it.

Back then I only knew who Sven Nys was. I had no idea who Mathieu van der Poel or Wout van Aert were. Wout actually won the elite race that year. There were around 60,000 people there – 100,000 in total over the two days. I remember climbing to the very top of a caged walkway and I was the only one up there to watch the finish. I took a video on my phone, but it couldn’t cope with the noise and couldn’t pick it up. It was just too loud at the finish for my phone. It was insane to see how the Belgians responded to a Belgian winning.

Going into the Junior World Championships in 2017, I was the favourite. I had only lost one race that season. It was the biggest goal I’d ever had, even right up until now. I don’t think I could ever be that targeted again. I even wore a face mask on the plane on the way over so that I wouldn’t get ill. I was that ahead of the times.

I don’t think I was nervous. I remember eating breakfast in the morning and thinking that it didn’t feel like it could actually be the Worlds that day. And then when we got to the course, it rained in between our practice and the race, and the ground was like sheet ice.

They had gritted the start/finish line but not the first corner, which was gravel. There were frozen puddles there and I knew there’d definitely be a crash there. So we started the race. I stuck to the inside line and just made sure I got around that corner, and behind me there was a massive pile-up.

After that, a French guy got away and took the lead. But after the second lap, I took the lead and got to work consolidating it and growing it and not making any mistakes. Then I heard on the tannoy that it was a British 1-2-3 and Ben Turner and Dan Tulett were fighting each other for second and third. I couldn’t believe it. I think they both crashed about five times each on the final lap. I was simply making sure I stayed upright. Then I finished, and then Dan and Ben, and we were all on the podium.

We had all ridden with black armbands. Charlie Craig had died two weeks before. Charlie had been one of the big talents of the youth scene and was for sure going to be a good rider. He’d died in his sleep. He just went to sleep and didn’t wake up. Cycling’s a small world; everyone knows everyone. To be honest, I couldn’t stop crying.

After every goal I achieve, the main feeling is simply relief that it’s finished. That’s what I always feel. When I stepped up to the elite, it took a while to adjust my mentality, having been used to so much winning. I had to learn to fight for places that I would not normally care about. I think that’s an important lesson for the whole of the rest of my career in the WorldTour on the road and with the elites in cross – you’re not always going to win. You have to try and fight for all the other places as well. But as time’s gone on, I’ve got stronger. So now I can race to win or at least to be on the podium.

The first part of this season, I was right there even though I was 17th in my first World Cup race. But once I got going, it was good.

The day before the Superprestige at Gavere, I had got on the podium for the first time in the season and I went home knowing that I’d be good the next day. I knew it. I could imagine the start and smashing it from the first lap, which is how I used to race as a junior. That’s how I won a Tour Series race in Durham and how I won junior Paris–Roubaix. I could sense that I was going to win, which sounds weird, but I’d imagine what I was going to do and then I’d do it. It was the same in Gavere. I needed to start well, go straight to the front and then smash it. It’s a risky strategy, but I always go better when I’m in the front riding my own race rather than trying to follow.

As the race went on, Mathieu van der Poel and Toon Aerts came across and I sat behind them a bit. Then I gradually got a gap, and Mathieu kept making mistakes. I actually assumed he’d punctured or something and that he’d get back to me, but then it became clear that he hadn’t and that I’d actually just gapped him. I wouldn’t say Mathieu was pleased to lose to me exactly, but his rivalry is much more with Wout van Aert, so he congratulated me. That was my first proper win. The first win that really mattered, I guess.

I don’t know Mathieu van der Poel and Wout van Aert that well. I’ve played Fortnite with Mathieu a few times. I quite like chatting to Wout when I see him after the podium. Me and Mathieu talk about cars sometimes. He is not happy unless he wins, whereas Wout measures it. He knows the days when he can go full, and he often wins on those days, apart from at the Worlds this year.

They’re both strong and explosive. Cross makes you fast. Strong and fast. That shows on the road with them and the way they are. Wout can climb better, as he showed at the Tour, but they can both win sprints and do well in the Classics. That’s what they’re about. I’m similar. I may not be as strong or as good at sprinting, but I have the same characteristics from cross as they do. I’m getting better at climbing in road races. Climbing and sprinting really.

The worse the weather, the better I am. Take, for example, Namur in 2020. It was the coldest I have ever been, for sure. When I got back to the camper van, I sat under every towel I could find, my whole body shivering uncontrollably until I could actually stand up to get in the shower. And that was after only an hour in the rain. I’d snapped my seat post off on the last lap, so I lost a podium place. But I think that might have been a blessing in disguise because I think I might have died of hypothermia otherwise.

In Namur they basically sent us riding down stairs. They put sandbags down, but they didn’t make much difference. Everyone was freezing cold. I was so cold I could barely hold my bars and then we had to go down these stairs, round a corner and then drop onto some cobbles where there was a puddle so deep you didn’t even know where the bottom of it was. It was massive and full of sloppy sand. Every lap I’d go around and try to brace myself for where I thought the bottom of this puddle was, but I never once got it right and I always had to put my foot down or just get off.

When you make mistakes, cross has a way of making you look like a numpty. You trip over going up the stairs or catch a handlebar on the fence or you just slide out, slipping around in the mud. You can look quite ridiculous sometimes, even the best riders in the world. Like in the warm-up for Overijse this year, on the first lap. It was a new course that I didn’t really know all that well. There was a downhill section into an uphill that you have to run because you can’t ride it. I jumped off my bike, slipped straight on my arse and slid straight towards a cameraman. As I got up, I said, ‘Did you get that?’ He said, ‘Of course!’ I think the mistakes make it more engaging for the fans. It resonates more; the mistakes make the riders seem more human.

If you’re even on just a slightly bad day, you can tell. It makes such a difference to the whole flow of your race, to the whole lot. You lose so much more time and ground from the start than you would in a road race if you felt bad. You start flat out – you sprint into the first corner – so immediately if you’re on a bad day there’s no time to find your feet like there is in a road race. You’re immediately on the back foot.

There is no way on earth anyone could possibly replicate a cross race in training. Even if you tried to simulate it, straight from the start and then going into a sustained effort, you could not come close to what you do in a cross race. But in the race you don’t really feel how it hurts. The faster you go, the more your adrenaline flows and the better it feels. That’s how I see it. When you are going well, and you can put laps or sections together and nail it perfectly, that’s a pretty good feeling. It can be intense. I got more and more involved in it because I was good at it, and it’s become my job now.

I could win the World Cup, but who remembers who wins the World Cup? I need to be the world champion. There’s nothing else.

Cyclingnews is the world's leader in English-language coverage of professional cycling. Started in 1995 by University of Newcastle professor Bill Mitchell, the site was one of the first to provide breaking news and results over the internet in English. The site was purchased by Knapp Communications in 1999, and owner Gerard Knapp built it into the definitive voice of pro cycling. Since then, major publishing house Future PLC has owned the site and expanded it to include top features, news, results, photos and tech reporting. The site continues to be the most comprehensive and authoritative English voice in professional cycling.