Thomas Dekker: A doper’s desire for redemption

Dutchman speaks frankly about past and future ambitions to race clean

In Lausanne, Switzerland, Anne Gripper nervously shuffles papers from one end of her desk to another. She looks up at the clock. 10 A.M. exactly. She sighs at the inevitable but grim task she must carry out and picks up the phone.

In Monaco, Thomas Dekker is dashing around his apartment. The Tour de France starts in three days and he’s not packed. As he scurries from one room to another, collecting enough kit to last three weeks of racing, the phone rings.

Dekker notices it’s a Swiss number but has no idea who it could be. He answers.

“Hello Thomas? Thomas Dekker?”

“Yes.”

“This is Anne Gripper from the UCI. I’m calling to inform you that you’ve tested positive for EPO.”

The rest of the call is a blur for Dekker. He says little. His body taken over with shock, surprise and fear as Gripper’s remaining words wash over him.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“When? How?” Dekker manages to mutter in a low, broken voice. She’s already told him but he hasn’t been listening.

The call ends and Dekker, now sitting at the end of his bed, is trembling. He looks at his half-packed suitcase, glimpses a look of himself in a mirror before bowing his head in tears. “I’m fucked,” he says to himself.

He calls his family, his friends and then his team. There won’t be a Tour for Dekker this year. There won’t be any racing for two years in fact. As a drug cheat in professional cycling he’ll be fired from his team and face two years out of the sport.

More importantly he’ll always be known as a cheat, someone who injected himself with illegal substances in order to con the sport of cycling, his employers, his fans and himself.

Dekker tested positive for EPO in an out-of-competition test carried out by the UCI in December 2007. Only after retrospective testing and careful study of his blood profile was his cheating exposed.

It’s now July 2010, exactly a year to the day since Gripper called Dekker. Looking well but slightly above weight for a professional rider, he’s in Belgium putting the finishing touches to his new house. The walls are still wet with paint and furniture is sparing to say the least but it’s a grand house nonetheless, with an expansive garden. As we walk towards the top of the lawn there’s a repetitive hiss coming from the sprinklers.

“That phone call turned my life upside down,” says Dekker as we sit in the garden. “I told her it wasn’t possible. I was clean then and she said that I was positive from December 2007. I knew exactly what she was talking about. I put the phone down and I called my family and my team.

“Of course there were a lot of rumours and I’d heard them. I heard that my blood values were suspicious. But I thought I was invincible, that they wouldn’t catch me. They saw the values were going up and down and then they decided to do some re-testing,” he says.

The following weeks after Dekker’s positive test read like a typical casebook of doper defence syndrome. First came the denial, then a call for re-testing before he began hitting out at the lab and vowing to clear his name. Amongst it all he even had time to have a pop at Ricardo Ricco, who received a far lesser sentence after apparently helping authorities.

“I was that stupid,” Dekker admits. “I look back now at what I was saying in the press and I can’t believe it.

“I doped in the past,” he says without too much prompting. “The story came out that I doped one time in the winter but when you think about it, when the blood passport is not okay…. I made some mistakes and I doped in the past. I am very sorry and I want to come back clean.”

When Dekker finally admitted his guilt it came with a footnote: that he’d taken EPO once, in December 2007 and tested positive, end of story. An insult to intelligence of fans but now Dekker is trying to turn a corner.

Perhaps in an attempt the wipe the slate clean and start again, the Dutchman is finally admitting that EPO was prevalent in a part of his career, or at least used for a substantial amount of time. Enough time for his blood profiling to arouse suspicion throughout 2008 and for the sport’s governing body to go back and retest his samples; enough suspicion for a number of teams to stay clear of him, including his old team Rabobank.

“It wasn’t just once. It was a longer period.

“I felt invincible,” he says again, looking down as his eyes begin to well-up. “At the time you don’t realise what you’re doing. You’re in this bubble and, and I doped in the past and that’s the story.

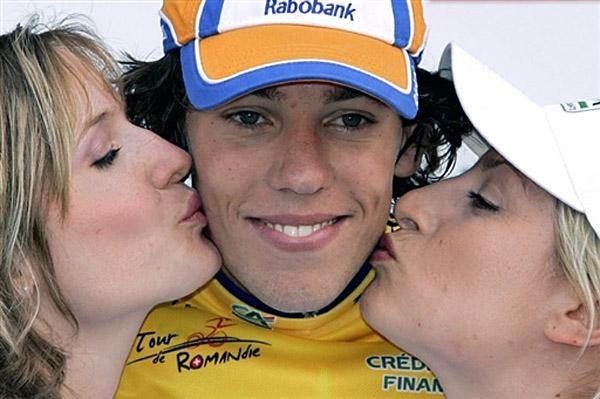

“Everyone can take what they want from the past and make their own conclusions. I didn’t dope to win Romandie or Tirreno, but I know what I did.”

According to Dekker, somewhere between those wins in the spring of 2007 and the end of the year, the Dutchman had switched from being one of the most gifted and clean sportsmen to a rider dependent on EPO.

While a rider like David Millar has become synonymous with talking openly about doping and naming the exact races he doped for, Dekker won’t go down that route. For him it’s not necessary.

“I get asked which arm I injected EPO into. I mean, I don’t want talk about that. Is that what people want? Do they really want me to talk about that? I’ll tell the truth, that I doped but I don’t go into too much detail. I know what I did and did not do and I know I won those races clean.”

He pinpoints the end of 2007 as the start of that slippery slope. At the Tour that year, Dekker’s first, his Rabobank team held the yellow jersey through Michael Rasmussen, but four days from Paris the Dane was ejected from the race for lying to authorities as to his whereabouts. Rabobank, who initially stood by their man, fired him and a re-structure of the team begins.

New management came into the Rabobank team, men Dekker describes as non-cycling people, and he quickly made a rod for his own back, speaking out against them at every opportunity. He’s had everything his own way for the last few years and now people that have no knowledge of cycling are telling him what to do. What do they know? They certainly don’t know that he’s invincible.

“I was wrong in my judgment about those people, because I was living in my own bubble. Now I know I was so wrong,” he says.

“I’d had problems all winter with my hip and then with the new team so at the end of 2007 I was feeling a lot of pressure. I wasn’t feeling myself in the team anymore. There was never any pressure from them though to use doping. I went out of my way to dope, I was responsible.”

Yet despite the drugs 2008 was a poor year results-wise. Dekker went from race to race in search of form, unable to find the legs that had helped him in 2007. But it wasn’t his legs that were the problem. He’d lost his head. The regimented life of rising early and training every day had disappeared as he became more reliant on drugs, ego, partying and being the centre of attention.

“I wasn’t living for my sport anymore and I was trying to make up for it by doping. Cycling was my life when I was winning races like Tirreno, I was waking up early, living like a professional should. I was never going out, just doing the same thing always living for my bike. In 2008 that was all different. I lost my seriousness and my focus.”

When his split with Rabobank finally came, the rumours of Dekker’s misdemeanours had already filtered through to the gossips, internet forums and blogs. The rider was without a team heading into the 2009 season, and with no results to speak of few teams were willing to take a chance. One prominent team even met with Dekker, took one look at his profile and decided to walk away. Run, in fact.

Eventually Lotto came in. The same team that hired Bernhard Kohl.

“It wasn’t hard to give up doping in the end. I was searching for a team, I just wanted to ride my bike again and get to a good level. I came to Lotto and I closed the door on what I’d been doing. I suffered so much with all the rumours and the controls and the doubts so then I didn’t want to do it anymore. Stopping was a relief and it felt great.

“I’d heard all the rumours about my blood values. Eventually I knew I had to stop. You can’t ask anyone for advice, I’d stopped making the stupid mistakes by then.”

According to Dekker he began living like a pro again. Riding clean, cutting down on the parties and extravagance and finding the passion and love for the sport he’d somehow lost. “I went to altitude for the first time in my life, I bought an altitude tent. I did everything the right way. It was really hard, I won’t lie, but then suddenly the positive test came out.”

Dekker pauses, his eyes still just at the point of crying as he draws a deep breath.

“I just wanted to ride my bike again and get to a good level. I came to Lotto and I closed the door. I suffered so much with all the rumours and the controls and the doubts so then I didn’t want to do it anymore.”

The question remains as to where Dekker found EPO, who provided it and how did he learn to administer it. On this he becomes vague.

“If you’re using recreational drugs you can’t buy them in the supermarket but everyone knows how to find them and it’s a little bit the same in cycling. Of course some people in my environment knew I was doing it but no one was saying to me, Thomas you have to do this or do that.”

No names, no trace of where the drugs came from. For Dekker it’s a closed door and something he won’t open.

“I was an amateur when it came to doping. I was losing grip on my life but it was me that went and found the EPO and me that took it. I’m responsible, so why blame someone else?”

We sit in silence for a few minutes, the repetitive hissing from the sprinklers still in the background.

“I want to come back and I think I can win races,” he says, smiling for the first time.

“I know that I have to prove again that I’m a good cyclist and I believe in myself. I know that guys like you, journalists, cycling fans, don’t believe me at this moment and I would do the same but I want to put it behind me. I have changed my life completely. I have moved from Italy to Belgium. I am working with a new trainer (Peter Pieters). I am living a tough training regime again and I have hired professional management in order to get me back in the peloton. The only thing I can do is win some races and show that I’m a good cyclist.”

Dekker pauses again. He perhaps knows I’m about to point out that winning races is almost pointless now, that riding clean and advocating for a drug-free sport are what will count if redemption is what he’s looking for.

“All my life I’m going to carry this, I’ll forever be a rider who tested positive and that’s something I have to live with but I don’t want to always live in the past,” he says.

“It’s going to be difficult to find a team, I know that. I’m just hoping to find a good team, come back in a clean team and ride my bike and ride some good races.

“I was young, I was stupid and I’ve seen a lot in my life. I’m 25 years old and I want to come back and have a long career. I love cycling. I just want to show that when I come back. I want the people to see that.

“Some riders have an opinion about me and that’s normal but I know I still have friends in the bunch and when the two-year suspension finishes I hope they give me a second chance and let me prove that I’m a good rider.”

The interview ends and Dekker lets out a sigh, as if to suggest that he’s got as much as he can off his chest. I look at him quizzically still like many, unsure.

He’ll face more of that once he steps back into the public eye and starts promoting himself as a clean rider. He walks me to my car and we say our goodbyes. The hissing has stopped and the only sound from his garden come from the chirping birds in the trees.

“You know what I really want?” he asks before I leave.

“When I’m 37 or 38 I want to look back and say that I did it all again but in the right way. I just want to come back and prove myself again.”

Dekker will find a team, there’s no doubt about that, and he will be competitive too. The progress the sport has made in the last few years proves that riders can race and win clean and while it’s still hard to swallow absolutely everything that Dekker says, due to the partial wall he still guards himself with, it’s clear that he wants a second chance. Let’s just hope that when he’s 37 or 38 he and the rest of the sport can look back at a rider who kept his word and whether he won or not, raced clean.

Dekker on his Cecchini friendship

Part of the wall that still surrounds Dekker could be due to his relationship with controversial doctor Luigi Cecchini and the Austrian investigation involving, amongst others, himself and former teammates Denis Menchov and Michael Boogerd. Dekker still maintains he has a personal relationship with Cecchini that doesn’t include any form of training advice.

“Of course I still talk with him. Look, I know his reputation, I know, but I can guarantee I never saw anything, he never said anything to me about doping. He never gave me any medication.

“He hasn’t been my trainer for around two years now and I learned a lot from him in the past. It was a big disappointment for him that I tested positive. He knew I was talented and saw all my test results and he blamed me when I went positive. He said I never needed to do that shit, that cycling had changed. He was right.”

Daniel Benson was the Editor in Chief at Cyclingnews.com between 2008 and 2022. Based in the UK, he joined the Cyclingnews team in 2008 as the site's first UK-based Managing Editor. In that time, he reported on over a dozen editions of the Tour de France, several World Championships, the Tour Down Under, Spring Classics, and the London 2012 Olympic Games. With the help of the excellent editorial team, he ran the coverage on Cyclingnews and has interviewed leading figures in the sport including UCI Presidents and Tour de France winners.