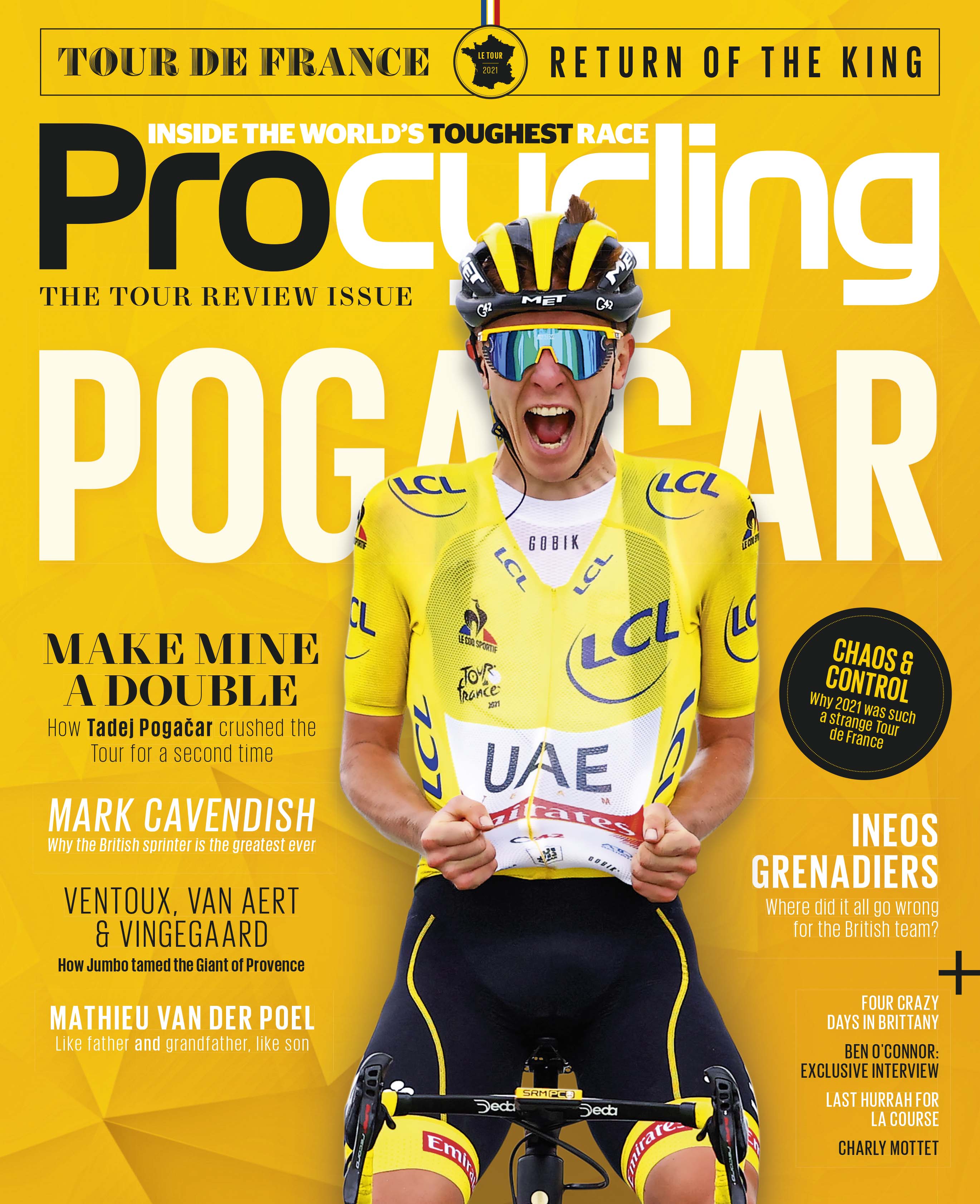

The Youth of Tadej Pogacar

Procycling looks at the inexorable rise of the young Slovenian and the likelihood of a long period of domination

Tadej Pogačar crushed the opposition to win his second Tour de France at the age of 22. Procycling looks at the inexorable rise of the young Slovenian and the likelihood of a long period of domination.

The first time I saw Tadej Pogacar at the grand départ of the Tour de France in Brest; I recall how he rolled onto the stage to great fanfare, though not as great a fanfare as the Breton riders, of course. Even then, I had to remind myself that off the bike, Pogacar’s probably a normal 22-year old kid, liking memes, spending his time in WhatsApp chats and hanging out with his girlfriend. But when he’s on a bike, he’s someone - something - else entirely.

I settled on the analogy of royalty pretty early on in my writing about him because I felt it fitted. As he stood there on a stage occupied by breakdancing French children not too long ago, his eyes peered out at all of us, his face the picture of relaxation, an easiness further cemented by the gentle slope of his shoulders, the casualness of his wave. Everyone else who had been up there held the palpable tension of preparing mentally to ride the most prestigious and arduous bike race in the world. Tadej Pogacar held himself as though he’d already won it.

The Boy Prince. That’s how I referred to him, because he was prince-like, had the confidence and innate authority of total control, external and internal, and yet, at the same time, a gentle, serene, youthful benevolence. He rules not by tyranny but by playfulness, more Machiavelli, less Ivan the Terrible. I think even then, before the race had started, I knew that Pogacar would win - that this would not be a democratic election to power but a coronation. And yet, I, like the rest, would have to wait and see. It was a shorter wait than anticipated in all those press conferences about how to fight the combined powers of Ineos’s fantastic four, how Roglic was shaping up after his weeks in isolation, whether or not Nibali or Kelderman were to be considered real contenders. But that’s bike racing. It doesn’t always unfold the way we’d all like it too. To Pogacar, the result was what it was, which was satisfying, which was the desired outcome, which was winning.

For the full three weeks of the Tour, I had only my powers of observation to go on, because there was no way in hell any of us in the lowly written press were going to get a chance to speak to him one-on-one, even before he took the yellow jersey. Trust me, it was a comedy of manners on my part, going back and forth with his press officer, trying to get him for just 30 seconds before stage 7, shouting “Tadej!” naively in the first few days in the mixed zone as though he would stop. Maybe he could answer my questions by email, was a WhatsApp message I got. I replied that the point was to observe him and be in his presence, not to actually ask him my questions. After that there was silence. After that, I sent back, defeated, “Email is fine.” There were never emails. Besides, what could one even ask a man like that, a man who seemed at once so simple and boyish and yet could destroy and make miserable his enemies with such apparent ease? What could one ask that hadn’t been asked before? What could one ask other than “How?” Which is a question he, like the rest of us, could not possibly answer.

Normal people

Tadej Pogacar was born to simple if uninspiring circumstances. His parents are emblematic of the first generation of the post-Yugoslavian middle class. His mother’s a French teacher, and his father works as a foreman in a factory that makes chairs. As a boy, he cried when his older brother Tilen was invited to ride for the Rog Ljubljana club - a club Pogacar would stay with until he went pro in 2019 - because he was not yet big enough to race bikes. When

he finally got one, it was nothing special, a green aluminum Italian make, but to him, it was everything. Pogacar confessed in the post- Tour press conference that he had crashed on his first ride because he didn’t know how to unclip from his pedals. This humanised him.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In fact, much of Pogacar is oddly normal. He’s not petit or compact or half-emaciated like most of his competition. For a bike racer, he’s rather stocky, and in normal clothes, one wouldn’t be able to tell that he was a bike racer at all. On the climbs, he can be rather ungraceful, bobbing around, pedalling, in the famous words of Tom Dumoulin, “like a coal miner”. And yet, despite this apparent inefficiency, he is exceptional. In a sport governed by arms races of technological advancement, marginal gains, and strategic brinkmanship, Tadej Pogacar simply rides his bike better than anyone else.

He has fun, too. This is actually one of the most endearing things about him, that he very viscerally loves riding his bike. That love is obvious to anyone who has the privilege to observe him. On the hellish slope of Luz Ardiden, I stood by the side of the road and watched him zip by impossibly fast round the penultimate hairpin, riding to another resounding win. Brown-blond hair poking out from his helmet in its signature tufts, his tongue hung out to lick his lips before they split into a smile - not a grimace but an honest-to-god smile. Stomping up that brutal gradient, he was having a good time, plain and simple. There was no greater joy to him than being one with himself and the human-powered machine around which he had oriented his entire life.

Cycling for fun

I asked a lot of riders about Pogacar. Back in February, I would bring him up with Roglic, who didn’t say much, other than they were still friends. I didn’t really believe that until I read on a Slovenian sports site that after Roglic had crashed out of the Tour, Pogacar would call every few days to check up on him. I asked his UAE team-mates about him, too. In the first week, Brandon McNulty characterised him as a “really nice, really chill guy”. Marc Hirschi called him “calm and relaxed”. Nice. Calm. These are the words to describe a pleasant boy who’s never been paralysed by the pressure to succeed simply because even if he failed, he still got a nice bike ride out of the failure. Matej Mohoric, a long-time personal friend, said of him: “He’s super laid back, super relaxed, just taking life one hour at a time, one moment at a time. He always just enjoys.” A concession: “Okay, maybe things have come a little bit easy for him so far, but he’s not really feeling any pressure.” Still, “He’s really, really persistent, also quite determined. He has no points to prove.” Mohoric then contrasts Pogacar to Roglic, who is entirely victory-driven, who is focused, who thinks of things like long-term achievements. “Of course, winning also means a lot to Tadej, but he’s a lot more relaxed, a lot less goal driven. He’s just enjoying life.” I didn’t quite believe this until someone asked Pogacar in the post-Tour conference whether he planned on winning multiple Tours. He looked at the journalist with slight confusion, as though he didn’t understand the question. He answered that at the moment, he was just thinking about the Olympics. One race, one day, one hour at a time.

This Tour, despite the increased attention, Pogacar has become gradually more comfortable with being himself. As soon as he steps off the bike, he’s a kid again and he does, well, kid stuff. He faved a meme on Instagram of Sepp Kuss photoshopped with a joint in his mouth, captioned ‘Sepp Kush’. He photobombed the video interview Mohoric did after winning stage 7. He gives fistbumps to the guys who roll past him in the mixed zone. He makes faces and sticks out his tongue. Sometimes, he becomes flustered and embarrassed, like when I asked him after stage 14 why everyone in his finishing group was sprinting at the end despite there being no time gaps to close, nothing to be gained.

“I don’t know huh? Everyone was going full gas...and then we had a little sprint,” he giggled. “It was nice to have a little kicker in the end, open the legs...that’s what we do. We enjoy the ride, we enjoy sprinting each other.” It was a moment when I realised that this was all a game to him, no different than any Saturday club ride. It was all in good fun. Other people agonised and buried themselves and suffered and looked at the race as some venerated site of glorified anguish. Pogacar looked at it and saw it for what it was: a bike race, and anything he did on the bike that seemed inexplicable could be explained by this. Why, people asked, would he keep attacking, keep going deep, keep putting in digs, keep wasting energy in the final Pyrenean stages even though he was so far ahead in the GC? Why would he be so okay with being isolated sometimes as early as halfway through a stage? Why would he sprint for even the minor of places? The answer is simple. He doesn’t think of cycling as some kind of micromanaged exercise in calorific budgeting. He’s a bike racer from another era, a bygone era, an era of individual triumph and prowess. It just so happens that Pogacar is good enough to ride like that, in that swashbuckling fashion in the face of all these powerful teams who function less like sporting outfits and more like small infantries, tightly organised with military discipline. Against them, Tadej Pogacar is a hand grenade thrown into the ranks.

Dynastic succession

I once watched a documentary on Eddy Merckx, in which it was portrayed how the Belgian would simply burn through his domestiques one by one until he would inevitably be out at the head of the race alone. Being a Merckx domestique was possibly the worst job in the peloton. When one looked at the battered ranks of UAE Emirates at the end of a mountain stage, after they’d finish minutes down on their pioneering leader - Hirschi with his dislocated shoulder, Rafał Majka with his bruised ribs, McNulty bearing the scars of two bizarre crashes - one got the sense that being a Pogacar domestique isn’t dissimilar. There were criticisms that his team was weak, perhaps unfounded. UAE Emirates just didn’t ride in the way strong teams are expected to these days - the Team Sky way, constantly on the front, boot on the throat from beginning to end. But also, like Molteni back in the day, UAE didn’t need to ride that way to win. They stuck with Pogacar until they could no longer, and then it was known that he was more than capable of fending for himself. That’s the mark of a team with no insecurity in its leader, which, in a way, is the strongest kind of team there is. And what would have been gained if they rode in a train? Nothing, not least because they couldn’t, after all the first-week crashes. No one could, and the race was better for it.

There’s a lot of talk these days about ‘dynasties’ - that we are at the dawn of a new one. People in the press room complained as soon as stage 5 that cycling was about to get boring again, like it was in the Froome era. And yet the dynasties, especially those of Merckx and Hinault, are seen as golden ages of the sport. As far as the negative comparisons go, Hinault was a tyrant in the peloton in a way soft-spoken Pogacar could never be. As for Froome, Pogacar doesn’t ride like him - his is not the impulse to control, to dominate. His is the playful instinct to see what happens. Still, as soon as Pogacar pulled out minutes on his admittedly reduced competition, suspicion started. It ranged from hushed whispers of a return of eras past to accusations of motor doping to pointing out the very real dark connections members of the UAE staff - Mauro Gianetti and Joxean Matxin specifically - had to the dirty times of yore. And Pogacar was asked about these. When asked, he first gave answers like, “I’ve never tested positive.” Cue social media handwringing: that’s just what Lance said. I’m not defending Pogacar here or insisting on his innocence, but he was born in 1998, and his cycling consciousness began with the Schleck brothers and ends with himself. It’s unrealistic and absurd to expect someone so young from a country so far removed from America to have an encyclopedic knowledge of EPO-era innuendos. Pogacar responded to the accusations with bewilderment, and other times, he was clearly annoyed, if not insulted. Mostly, he came off as a little naive. “I come from a good family and my parents raised me to be a good boy,” is what he said on the second rest day. It’s about all he could say. Anything else would get contorted into an analogy to something someone else said in guiltier times. It’s notable, too, that even Pogacar refers to himself as a boy

The boy king

I remember the day Pogacar slipped on the yellow jersey after his spectacular solo attack to Le Grand-Bornand. It was drizzling and fog swept over the valley and the steep alpine slopes as they rolled in one by one, with great distances between appearances, starting with Dylan Teuns and ending with a beleaguered and defeated Roglic, his last finish. I lingered despite the awful weather because I wanted to see Pogacar in his moment of transition from white jersey to yellow. I wanted to see him when he came back to the mixed zone after the podium ceremony to do the television interviews, because I had the distinct sense that this was a very poignant thing to do, this waiting, this observation, even though there was no hope for me to speak to him.

I remember how he rolled up to the Eurosport pen in fresh yellow lycra, something about him relaxed, at ease, more so than usual. Dignified and quietly, he spoke, his mellow voice drawling in the casual way it does. What he said, I can’t recall, just that he was where he was supposed to be in that jersey, on that mountain, in the rain. Pogacar doesn’t like to look into the TV camera when he speaks. He never has. As I stood behind the camera operator, he stared at me dead on, just as something alive and unthreatening to lock onto, and because I was so clearly staring at him, almost in defiance, as though to say that I had every right to be there as he did.

On that day, in the misty rain-fog, his era had begun. On that day, our boy prince donned his golden cap and became, unquestionably, a king. When he finally broke the stare, I walked away changed by it. I felt like I had just observed his own history unfold in minutes, in real time. Dynasties changing hands, the race ending, already won barring mistakes he would never make. There was a gravitas to his parting, his casualness suddenly vacated. He had accepted his role, his fate. He would be expected to win like this and would live under a magnifying glass for it. His world would be different now. So would mine for having the opportunity to chronicle it. So would cycling’s, which, for the next few weeks, if not the foreseeable future, looks very much like it is going to be ruled by monarchy.

Kate Wagner is a Chicago-based writer and critic. Her work on cycling can be found in various publications including Procycling. Her newsletter covers cycling in an unconventional fashion, featuring essays, short stories, multimedia works and illustration.

She can be found Tweeting at @derailleurkate