The Yellow Jersey Club: Marco Pantani and the romance of the 1998 Tour de France

Excerpt from The Yellow Jersey Club by Edward Pickering

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Yellow Jersey Club, by Edward Pickering, looks at the characters and personalities of the Tour de France winners between Bernard Thévenet in 1975 and Chris Froome in the 2010s, putting them into historical and cultural context. This is an extract from The Yellow Jersey Club, featuring the chapter on Marco Pantani, who won the race in 1998. It looks at the complex legacy left by the late Italian.

Marco Pantani, 1998

For Sonny Liston, it was easy being a superman. It was being a man that was often difficult - Boxing Yearbook, 1964

What explanation is there for the fact that millions of pilgrims flock to view the Turin shroud whenever the Cathedral of St John the Baptist in Turin puts it on public display, other than that people have a profound need to believe in incredible things? It was believed by the faithful that the shroud was stained with the image of Jesus, miraculously formed when he was wrapped in it after falling from the cross – until 1988, when a carbon-dating test run by Oxford University found that the shroud was a medieval creation, just over 700 years old. Yet on the three occasions the shroud has been put on display since, millions more still made the pilgrimage to Turin to see the image of Jesus.

Cycling fans are still worshipping at the church of Marco Pantani. He is the personification of romance in the sport – his climbing verve, bold attacks and psychological fragility appealed to a common and significant tendency in sports fans, that of imbuing human achievements with superhuman status. It’s either a natural thing to do, or so culturally ingrained that it might as well be – and why not? What better way of dealing with the daily grind than to enjoy a few fleeting moments of escapism, via the exploits of great athletes, or great musicians, or great actors?

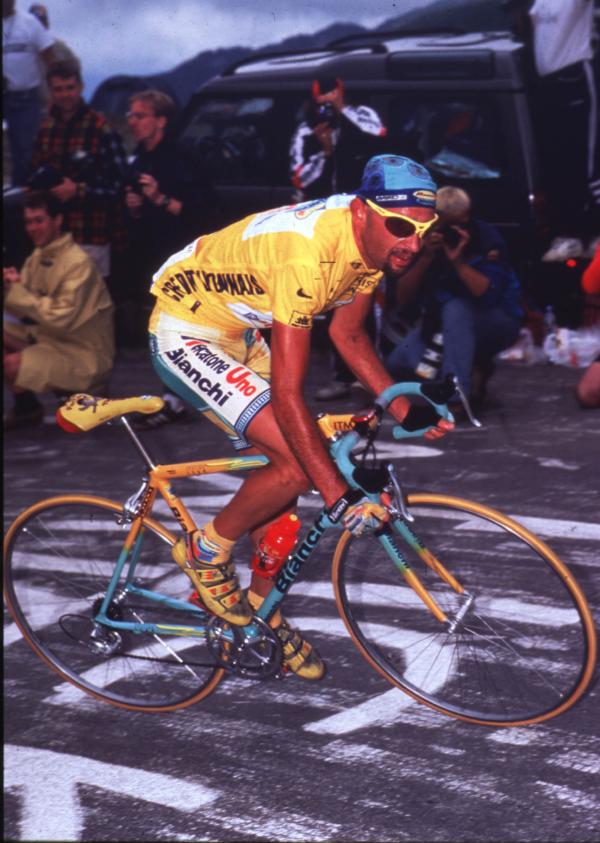

Pantani was easy to idolise. He won the 1998 Tour de France in spectacular circumstances – with a long-range attack in atrocious weather in the Alps – which was a throwback to the old days of cycling myth, when eyewitnesses and coverage were so scarce that creative newspaper journalists could essentially invent the narrative in purple prose. His unpredictable, organic, harrying tactics were a refreshing contrast to the metronomic, implacable, bullying strength of Jan Ullrich, his main rival that year. The 1998 Tour was a clash of cultures, stereotypes and cycling ideologies: the Latin versus the Teutonic, the climber versus the rouleur, the attacker versus the defender, Romanticism versus Classicism, the underdog versus the favourite, fire versus ice.

Cycling fans loved Pantani. He was capable of riding at great speeds uphill, despite looking inelegant on his bike – his riding style and attacks resembled a persistent wasp spoiling a picnic. He looked quirky – he’d covered up his premature baldness by shaving his head, cultivating a goatee beard and wearing a bandana, earrings and a nose stud (he might not have stood out now, but in 1998, not many professional cyclists wore facial jewellery). His sticky-out ears and crooked smile made him seem accessible, normal and likeable. He wasn’t good-looking, although when he was off the bike, his neutral facial expression was unusually placid – or maybe that was just in comparison to the grimace he wore when cycling. There was also a vulnerability about him, which appealed hugely to cycling fans.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

However, as well as the glorious cyclist, there was also the depressive, the cheat, the drug addict, the fallen hero, the psychologically damaged victim and, ultimately, the unspeakably horrible, lonely death in a seedy hotel room in the eerie quiet of an off-season seaside town.

Would it ever have been possible to have one without the other? Is it possible to celebrate the cyclist, and enable his ascent to the emotional heights, without somehow playing a part in his descent to psychological obliteration? Pantani’s psychological complexity and addictive personality got him hooked on the adulation, and the withdrawal symptoms eventually killed him. He made people happy, but he was not happy.

Pantani the cyclist and Pantani the person seemed inseparable from each other. In life, Pantani was given to profound and honest ruminations about his nature and thoughts. Consider his post-stage quote on the crucial stage of the 1998 Giro d’Italia (which he also won), when he’d attacked on the summit finish at Montecampione: ‘I just thought, either it works, or I’m going to blow everything. I had no alternative. I had to see, to know who was the strongest,’ he said. Then he continued: ‘When I had my nose pierced on New Year’s Eve, it was a symbol of my independence, that I didn’t want to be told what to do by anybody. With three kilometres to go, just before I had to attack, something told me to throw it [the nose piercing] away.’

There’s a depth to these words which is unusual in the run-of-the-mill quotes people expect to hear in the aftermath of a stage. The sense is less of a sporting competition to be won – with dispassionate tactics and superior strength – and more of a compulsion, and a degree of self-exploration that is frightening in its intensity. Pantani seemed to be harnessing not just physical and mental strength, but also emotional force. We loved it. But nobody realized that the adulation wasn’t a byproduct of the primary aim – winning races. Pantani actually needed it.

In Matt Rendell’s book The Death of Marco Pantani, which is comprehensive on the subject, there are forensic accounts of blood values, doping and the races he won that leave little room for theorizing about Pantani’s sporting ethics – there is no doubt he was taking EPO from at least early 1993. But there’s also a psychiatric report on Pantani, undertaken in 2002 by Dr Mario Pissacroia, who was a specialist in substance abuse. Pissacroia diagnosed both depression and bipolar disorder in Pantani, along with narcissistic and obsessive elements. He also deduced that Pantani had been using crack cocaine. But the terrifying thing about the report is one of Pissacroia’s conclusions, that Pantani experienced high stress from sporting competition. The point is that narcissism and obsessiveness are often seen as assets for an elite athlete – we celebrate the self-belief of someone who has become the best in the world at what they do, and admire their ability to organize every last detail in their lives in order to harness their talent. The conclusion Pissacroia came to was that involvement in competitive cycling didn’t help Pantani, it actually made him worse. Pantani’s life was a tragedy in the dramatic sense of the word: a worthy protagonist, weakened by character flaws, put into a difficult situation, whose fall is inevitable, and fatal.

If that wasn’t enough, there’s more bitter irony in Pantani’s career. The 1998 Tour de France is defined by two things: Pantani’s glorious victory, and the Festina scandal, which almost made the race grind to a halt. And while fans and the general public shared a sense of shock at the revelation that there was organised, endemic doping happening in cycling, they still cheered a winner whose blood records indicated career-long EPO usage. What’s more, Pantani’s 1998 Tour samples, when retested in 2004, demonstrated that while the race had been falling apart around him, while riders were arrested and detained for possession of doping products, he was taking EPO all the time.

The Festina scandal erupted in the run-up to the 1998 Tour. A Festina team car, driven by their soigneur Willy Voet, was stopped as he crossed the border from Belgium into France on his way to the race. The car contained a staggering range and number of doping products, a mobile library of pharmacological research from which riders could borrow at will. This went beyond individual riders testing positive – the realisation that the team infrastructure was involved in the cheating elevated matters to an entirely new and more serious level. France had also recently passed a law making doping a criminal offence. The shining of light into cycling’s dark corners, still ongoing, had begun.

The Tour tried to tough it out – the prologue took place in Dublin, with Britain’s Chris Boardman taking the yellow jersey (and Pantani finishing 181st out of 189 starters, 48 seconds behind). The show went on – commentators commentated, primarily on the action, and the riders kept racing, although an anonymous professional once told me that the ferry crossing from Ireland to France was enlivened by the sight of worried riders emptying their stash overboard before the French police could start sniffing around once the race reached the mainland. The Festina riders got as far as the end of stage six before their situation became untenable and the Tour organization threw them off the race on the morning of the first long time trial.

This incident provided an interesting comparison between French idol Richard Virenque, Festina’s leader and the runner-up to Jan Ullrich in 1997, and Pantani. Virenque was devastated at his exclusion from the Tour. He and the Festina riders called an impromptu press conference in which Virenque sobbed his denials. Virenque, like Pantani, was dependent on the adulation of the public. But after this episode, and eventually confessing to doping, Virenque was back racing with no hint of self-doubt or regret and he retired happy in 2004, having won a total of seven King of the Mountains titles and three more Tour stages to add to the four he already had. Pantani’s dependence on public adulation was rooted in insecurity and mental fragility; Virenque’s was based in having a huge ego and an almost complete absence of self-awareness – he was as uncomplicated as Pantani was complex.

Ullrich won the long time trial, with Pantani another four minutes behind, but the Italian’s fightback started in the Pyrenees. He squeezed 20 seconds out of Ullrich on the stage to Bagnères-de-Luchon, then a minute and a half at Plateau de Beille. Against the backdrop of more scandal – Rodolfo Massi of the Casino team would be arrested, the TVM team’s hotel rooms raided – the riders collectively decided, with a demonstration of self-righteousness that would be staggering now, to protest against their treatment. The day after Plateau de Beille, they staged a sit-down protest while their self-appointed representatives, Laurent Jalabert and Bjarne Riis, bickered with each other and with the Tour’s boss Jean-Marie Leblanc. Tour de Farce, wrote the headline-makers, shooting into an open goal.

As a sporting spectacle, the 1998 Tour had questionable worth. First, there were more important things going on. The Tour organisation were set on the race finishing as planned – they simply didn’t have the imagination to consider any other options – but the ongoing police raids and scandal made it clear that the problem was huge. Secondly, many of the riders, including the two main protagonists, were still taking EPO. It meant that the race, and the narrative that the organisers and many commentators and cycling media were writing, were essentially fiction. Entertaining fiction, but fiction nonetheless.w

But why, then, is the Deux Alpes stage of the 1998 Tour still such a compelling spectacle? I can take or leave the rest of the race – as a sporting spectacle it was worthless. But watching video footage of that stage, or reading about it, is like picking at a scab – both painful and irresistible.

Ullrich wore the yellow jersey going into the stage. Bobby Julich was in second, just over a minute behind, while Pantani was fourth, three minutes in arrears. The weather was atrocious through the stage – chilly rain soaking the riders and huge, thick cloud blanketing the race – reflecting the rumbling thunder of doping scandals which followed the Tour from start to finish, and beyond. The terrain suited Pantani, to a point – while the Col du Galibier was perfect for his climbing skills, the long, draggy descent to the foot of Les Deux Alpes was less so. The summit finish itself was hard, but not at the same level of difficulty as Alpe d’Huez or Plateau de Beille.

Pantani attacked on the Galibier, his turquoise and yellow Mercatone Uno kit greyed and muddied by the rain and grit, but illuminated in the headlights of the following cars and motorbikes. He crossed the summit just over two minutes ahead of Ullrich. At this point, there was no danger in terms of time conceded by the German – he could expect to put minutes into Pantani in the final time trial, and his cushion was already three minutes. But the body language and presence of mind of both riders was telling. Pantani stopped to put on a rain jacket, his frozen hands and arms incapable of the dexterity needed to do it on the bike. Ullrich didn’t put on a rain cape, and his cadence was sluggish. His face was swollen, as if he was absorbing the rainwater through his skin. ‘He looked like a boxer,’ said his teammate Bjarne Riis.

Ullrich suffered on the descent, but the gap was still only four minutes at the bottom of Les Deux Alpes. If he conceded only one more minute in the next 10 kilometres, he would still be in a strong position to win the race comfortably. Instead, Pantani put another five minutes into him.

The iconography of the stage was overtly religious. L’Équipe’s headline was ‘Pantani au plus haut des cieux’, which translates as ‘Pantani on high’ or ‘Pantani in heaven’. There is a French hymn called, Gloire á Dieu au plus haut des cieux (‘Glory to God on High’). L’Équipe also reported his victory salute: ‘As he crossed the finishing line, he closed his eyes and spread his arms, like Christ on the cross. This man has forged himself in suffering.’

He took the yellow jersey by five minutes on Les Deux Alpes, then was the only rider strong enough to respond to Ullrich’s attack the next day on the Col de la Madeleine. But sporting intrigue enjoyed only two days in the spotlight. The next day, the riders went on strike again, the Spanish teams pulled out, and the race limped on to Paris, not quite mortally wounded. The fact that Pantani only conceded two and a half minutes to Ullrich in the final time trial, coming third, underlined the distorting effect EPO had on bike racing. Pantani had won the yellow jersey, but the taint seems even now to be incompatible with the feeling of excitement generated by the Deux Alpes stage. Without EPO, there would be no Deux Alpes. We don’t want EPO in the sport, so what does that say about our enjoyment of Les Deux Alpes?

Pride before the fall

Pantani grew up in Cesenatico, a small seaside town on the Adriatic Riviera. His father Paolo was a buttoned-up disciplinarian who occasionally administered corporal punishment to the young Marco. The psychological issues caused by this remained with Pantani for the rest of his life – when Pantani was withdrawn from the 1999 Giro after failing a health test, the moment at which the brittle foundations of his self-esteem definitively cracked for ever, he admitted that one of his first reactions on seeing his father was the combination of shame and fear he felt when he’d been in trouble as a child. Pantani’s mother Tonina, on the other hand, was described by his manager Manuela Ronchi as an ‘emotional volcano’. Tonina was a formidable woman, the very stereotype of the Italian mother, yet prone to personal crises – she attempted suicide when Pantani was a baby.

Pantani grew from hyperactive toddler, through introverted but headstrong child, to awkward adolescent, while his path into two-wheeled sport was the usual one for any Italian teenager – he couldn’t play football, so he cycled. Cycling brought discipline to Pantani’s life, and he was a born physical talent, but it also exposed a reckless, self-destructive streak which didn’t help his mother’s anxious temperament.

Pantani, whether through bad luck or the ability to override sensible limits, was prone through his entire cycling career to bad crashes. He was hit by an oncoming car on a ride in 1986, which caused him a ruptured spleen, then hit a van during a sprint with his friends, which caused significant facial scarring. There would be more serious crashes, throughout his career, including the one in the 1995 Milan–Turin race in which a car had found its way onto the race route. Pantani rode into it on a fast descent, and suffered a serious fracture of his left leg – it would be a year and a half before he could race seriously again.

As a cyclist, Pantani was destined for greatness. His climbing talent was immediately clear, and he won the Baby Giro, the amateur version of the Tour of Italy. He turned professional in 1993, and emerged as a star in 1994. In the Giro d’Italia that year he was completely unknown internationally but, in winning two stages and contributing to the first defeat of Miguel Indurain in a Grand Tour since the Spaniard had won the 1991 Tour de France, he became the darling of the cycling world. Balding, still wearing a monk’s halo of wispy blond hair, fresh-faced, big-eared and awkward, he beat Indurain and came second overall, behind Russian Evgeni Berzin.

He made his Tour de France debut the same year, and Indurain, now at the very top of his form, personally saw to it that Pantani wouldn’t enjoy the same freedom to attack him as he had in Italy. Pantani conceded 11 minutes to Indurain in one time trial alone, but he still rose to third overall by the end of the race.

Injury kept him out of the 1995 Tour of Italy, but in the Tour de France he won two stages. 1997 was almost the same again, following his comeback from the Milan–Turin crash. A crash caused by a black cat – what else? – running into the road during the team time trial forced his withdrawal from the Giro d’Italia, then he won two stages at the Tour, finishing third overall. At this point, cycling fans and the media were on Pantani’s side – his attacking riding and time-trial defeats made him easy to support, in contrast to Indurain and Ullrich, whose defensive, negative Tour wins were impressive but too well-planned, too cold to be emotionally engaging. So when he won the Giro d’Italia in 1998, followed by his Tour, it was a refreshing antidote to years of domination by time-triallists.

But Pantani soon found out how fickle the media can be. When he raced through the 1999 Giro and dominated his rivals with insouciant ease, the voices of dissent were already starting to make themselves heard – Pantani winning every mountain stage turned out to be as dull and predictable as Indurain winning every time trial had been. Journalist Angelo Zomegnan’s editorial in La Gazzetta dello Sport sniffed disapprovingly about Pantani leaving few crumbs for his competitors as he gorged himself on stage wins and time gains. While the public swooned at their hero’s feats, journalists grumbled about the lack of variety. It put Pantani into a defensive, prickly mood, but that would soon develop into full-blown paranoia when, with two stages to go, he was given a morning blood test in the town of Madonna di Campiglio by the UCI. His haematocrit level was 53 per cent.

In 1999, the UCI’s blood tests were branded as ‘health checks’ – a very blunt tool to keep rampant EPO use if not under control then at least within certain limits. EPO usage boosts the number of red blood cells in the body, thus improving oxygen-carrying capacity and therefore endurance. One of the side effects of taking too much EPO is death, from the blood thickening to the point that the heart can no longer pump it. In the mid-1990s, riders, including Pantani, were being measured with haematocrit levels of 60 per cent, a level impossible under normal circumstances. The UCI’s limit of 50 per cent, if breached, wouldn’t count as a positive test (EPO was still undetectable) but riders would be withdrawn from competition.

The irony is that the tests were a piece of cake to beat. It can only be surmised that Pantani’s 53 per cent haematocrit level was down to a mistake by either him or the individuals who facilitated his doping. Either way, the mistake had cost him the Giro with only two days to go, but he would have been free to return to competition in two weeks, and defend his Tour de France title. But the Madonna di Campiglio blood test instead marked the point at which Marco Pantani’s life arced gently beyond its apex and began a terrifyingly vertiginous descent via paranoia towards tragedy.

In The Death of Marco Pantani, Matt Rendell writes about dietrologia, a specifically Italian concept in which individuals are obsessed with hidden, conspiratorial reasons behind events. The travel writer Tim Parks writes in his book Italian Ways of a similar paranoid streak in Italian society, known as campanilismo, which is an ‘eternal rivalry that has every Italian town convinced its neighbours are conspiring against it’.

Pantani railed against the perceived injustice, citing a powerful, unnamed conspiracy against him. Pantani, in his pride, simply couldn’t deal with the shame of the association with doping – he’d built his self-esteem and identity on success in bike racing to the point of denial about the methods he was using, and the blow to his ego was mortal. Many observers have stated that Pantani was never the same after Madonna di Campiglio, but actually he was exactly the same – only more so. Perhaps he realised that he’d been part of a collective hypocrisy in cycling – able to smile his way through the 1998 Tour de France and enjoy the spoils of victory while others were taking the blame for the doping – but didn’t have the courage to admit it. Perhaps he’d thought that, as a sporting icon, he was untouchable. But rather than confront his problem, he hid behind his denial. It was not long after Madonna di Campiglio that Pantani started using cocaine. The cycle of self-destruction had begun.

Pantani came back and won two stages at the 2000 Tour de France, although stomach problems forced him to withdraw from the race before it ended. But his physical and psychological deterioration was starting to accelerate. His enablers in this were a motley collection of hangers-on and friends. And, in a small way, the cycling world, which continued to idolise his triumphs while trying to ignore the cognitive dissonance caused by thinking too hard about how he achieved them.

In February 2004, he checked into a hotel room in Rimini, where he accidentally overdosed on cocaine, a shocking, poor, shadow of the man who had won the Tour de France.

‘Lord protect me from my friends; I can take care of my enemies,’ wrote Voltaire.

Marco Pantani died a lonely, ugly death, caused in the end by a terrible alchemy between what he achieved, what he was, and the way the world viewed it.

This is an extract from The Yellow Jersey Club, by Edward Pickering, published by Penguin books. The rest of the book covers all the Tour de France winners between Bernard Thévenet and Vincenzo Nibali.