The Two Gentlemen of Verona: Moser vs Fignon at the 1984 Giro d'Italia

A controversial Giro ends on a fitting note inside Verona's Roman amphitheatre

This article was first published in 2019.

"I don't believe in miracles," Francesco Moser told the scrum of reporters tightening around him after stage 20 of the 1984 Giro d'Italia.

On the podium in Arabba, while Laurent Fignon was being helped into a fresh pink jersey, Moser was covering his own, sweat-soaked one in a long-sleeved GIS jersey.

"I'll probably lose the Giro now for an 11th time," Moser continued, "and only by a few seconds."

Fignon's solo victory on the Dolomite stage had seen the Frenchman move ahead of Moser to the top of the overall standings. With two stages remaining, he now led Moser by 1:31. It was a healthy advantage, although Fignon struck a cautious note.

"He can take a minute on me in the time trial, so I think I can win the Giro," Fignon said, "but I still have to be very careful."

Fignon's circumspection proved to be well founded. Despite Moser's protestations, the Italian had been conjuring up apparent miracles all season long. He hadn't contended realistically for the Giro since the late 1970s, but after appearing in gentle decline in his early 30s, Moser enjoyed a remarkable resurgence in 1984. In January, he broke Eddy Merckx's Hour Record in Mexico City. In March, he soloed to a win at Milan-San Remo by 20 seconds.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Suddenly, at almost 33 years of age, he had led the Giro for two whole weeks. Not only was Moser the strongest time triallist in the race, he was also limiting his losses to the winner of the previous year's Tour de France in the few high mountains that punctuated this rather benign Giro d'Italia course.

"I've improved a lot in the mountains, but that hasn't prevented me from having a few crises," Moser said of his climbing on the 1984 Giro.

In contemporary reports, his trainer Francesco Conconi was hailed as the guru behind the transformation, although as time went by, questions would eventually be asked of the legitimacy of his methodology. In 1999, Moser would finally confirm the long-held belief that he had received blood transfusions ahead of his successful Hour Record attempts, although the practice was only outlawed by the IOC in 1985.

That controversy was all in the future in June 1984, when the polemica centred on some rather more visible helping hands. After the Arabba stage, Moser was handed a largely symbolic time penalty of five seconds for receiving repeated pushes from overly enthusiastic tifosi. More egregiously, Moser had appeared to benefit from the slipstream of motorbikes and cars when Fignon and Roberto Visentini went on the offensive on the Tonale two days previously.

On that occasion, Visentini couldn't hide his disgust during an appearance on the post-stage Processo alla Tappa chat show.

"It's a Giro that was already decided beforehand in favour of Moser," said Visentini. "When we dropped Francesco, the road between us filled with cars and motorbikes."

That stage had already begun in a polemical vein, when the race organisation announced that the mighty Stelvio had been cut from the route due to the risk of an avalanche. Like Visentini, Fignon and his Renault manager Cyrille Guimard were convinced the rules of the race were being rewritten on the hoof to favour Moser. Photographs from the mountaintop suggested the road was passable.

"Stages were being changed day by day according to their interests," Fignon wrote in his 2009 autobiography, We Were Young and Carefree. "It was surreal."

The curious application of the rules continued even after Fignon had forged cleared on the Passo Pordoi to claim the stage win and the pink jersey in Arabba. While Moser was docked the aforementioned five seconds for receiving pushes on the Campolongo, the blow was cushioned by the news that Fignon had been handed a heavier, 10-second penalty for feeding in the final 20km.

By that point, Visentini's overall challenge had collapsed, largely because he had become so discomfited by the continuous abuse that rained upon him from Moser's legions of fans on the roadside. It pushed him to the brink of retirement. After finishing the Giro in 18th place, he sawed his bike into pieces and brought it to the home of his manager, Davide Boifava.

"I took the pieces to Boifava in a plastic bag," Visentini said in 2017. "I said, 'Here's your bike. I've had enough.'"

Writing in La Stampa, Gianpaolo Ormezzano, a doyen of the press room, took a nuanced view of Giro director Vincenzo Torriani's obvious determination to tailor the race to favour Moser's prospects at every turn. 'The Sheriff', after all, was good for business.

"Visentini, in good faith, always sees conspiracies and ambushes. Moser, likewise, sees everything as normal and clean," Ormezzano wrote. "The truth, and not just in cycling, doesn't exist. And if there is truth, it's relative to everybody."

The race of false truths

The 1984 Giro d'Italia, of course, finished with a race of truth, even if it, too, was all relative, on the 42 kilometres from Soave to the Roman amphitheatre in the heart of Verona. Third place in the bunch sprint at Treviso had netted Moser a 10-second time bonus on the penultimate stage, meaning that he began the final time trial 1:21 off Fignon's maglia rosa.

"I'll give everything, but I'm starting before Fignon, so he'll have all the encouragement," Moser said.

Moser was rather understating his chances. He had already won the opening prologue in Lucca and the 38km time trial in Milan at the end of the second week, putting almost three seconds per kilometre into Fignon on each occasion. A similar performance on the road to Verona would put him comfortably into the pink jersey by day's end.

Equipped with a road version of the low-profile bike he used to break the Hour Record, Moser had both an aerodynamic and psychological edge over Fignon. The Frenchman rode the test on regular dropped handlebars, while Moser was tucked into bullhorn handlebars and using disc wheels.

"A little before the start, when I saw he was riding on his Hour Record bike, I understood that it was probably done," Fignon wrote in 2009. "We calculated the benefit of that equipment to be two seconds per kilometre."

It wouldn't be the last time Fignon would lose a Grand Tour on the final day to a rider with a more advanced machine, even if Guimard vowed on that June afternoon in 1984 that the lesson had been learned.

"Now that we know these bikes are allowed, we'll equip ourselves with them," he told La Stampa. "Perhaps we'll make even better ones."

Fignon duly used bullhorn handlebars en route to victory at the 1984 Tour, but, crucially, was still using them when Greg LeMond had switched to tri-bars five years later.

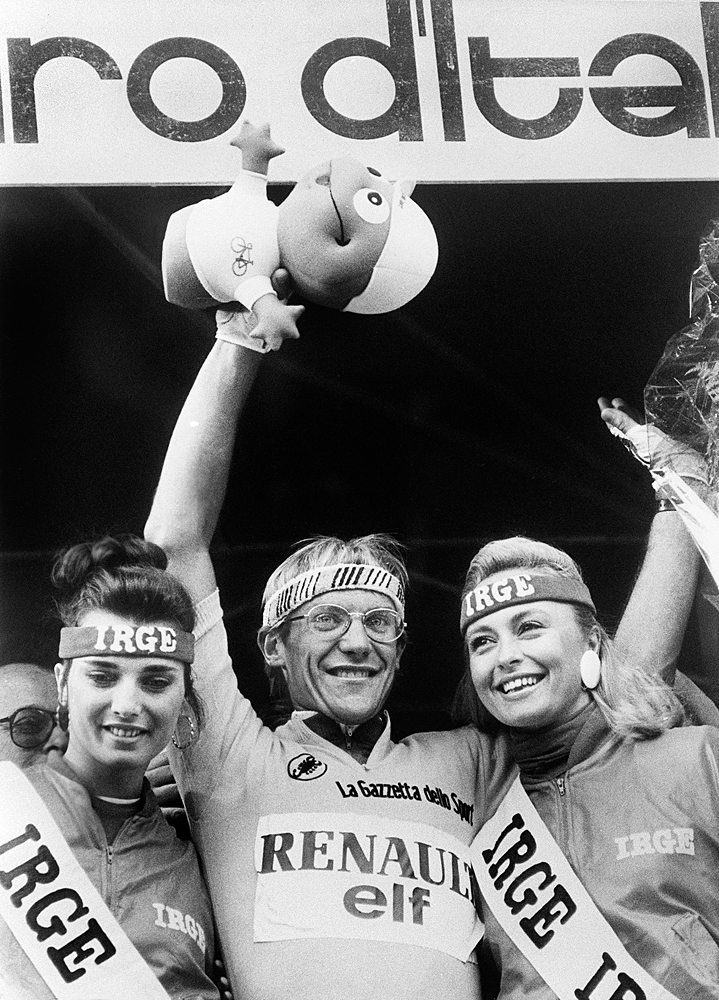

On this afternoon in Verona, meanwhile, it was clear from the first time checks that, barring accident, Moser would retake the pink jersey and claim the first – and only – Grand Tour of his career. When he wheeled to a halt inside a heaving Arena di Verona, the clock read 49:26. His average speed of 50.977kph was itself a record for a time trial over 20 kilometres. A giddy crowd waited, more in expectation than in hope, for Fignon to fall well short of his time.

Fignon, informed of Moser's progress, knew early on that he was racing only for pride. He placed second on the stage, albeit some 2:24 behind Moser. In the overall standings, he finished 1:03 down on Moser. As if to reflect the lack of mountains on the route, Italian champion Moreno Argentin, a Classics rider by vocation, placed third overall, 4:26 back.

In the immediate aftermath of the stage, Fignon managed to wrap his disappointment in diplomacy for local reporters.

"The result speaks for itself," he said in the arena. "I knew that Moser was gaining decisively on me and I went flat out. I have regrets, of course, but I lost against a champion who produced an extraordinary performance."

It was only after the fact that Fignon became altogether more forthcoming with his doubts about the legitimacy of Moser's performance. The television helicopter, he complained, had deliberately flown low over the time trial route, propelling Moser along the course while hindering his own progress.

As the journalist Pierre Carrey notes in Giro, a newly-published history of the Corsa Rosa, the helicopter was not mentioned at all by L'Equipe in the three days that followed the 1984 race, but the conspiracy theory had already hardened into accepted fact by the time Bernard Hinault lined out at the Giro the following year. La Vie Claire team owner Bernard Tapie even claimed he would intervene with his private jet if he saw foul play from the Italian television helicopter.

"You can see from the images," Fignon told Procycling magazine in 2004. "They are all from low down and behind him, so that the blades of the helicopter were pushing him along. Then look at the pictures of me and they're all taken from in front of me, so that while the helicopter was pushing Moser along, it was pushing me back."

Moser, for his part, has always firmly rejected the idea that he was aided by the television helicopter.

"The route went through urban areas where it was impossible to fly at low altitude. Besides, I was riding better than Fignon. In the prologue, I gained three seconds per kilometre," Moser told L'Equipe in 2017. Indeed, immediately after descending from the podium in Verona, Moser confessed that his downbeat pre-race prediction had been a bluff; Conconi had calculated that he could gain as much as three minutes on Fignon.

It is usually overlooked, mind, that Fignon's final deficit of 1:03 was almost equivalent to the time he surprisingly lost to Moser on the Blockhaus on stage 5. Already in pink after Renault's team time trial win, Fignon buttressed his lead by placing second behind Argentin on the Colle San Luca in Bologna, only to carelessly concede 1:01 to Moser when he suffered a hunger flat in the closing kilometres of the Blockhaus.

Then again, as Visentini had repeatedly warned in his role as the doomed Cassandra of this particular epic, the script of the 1984 Giro d'Italia had been written long in advance. It was preordained that Francesco Moser would parade into Verona's amphitheatre in triumph. Destiny – or perhaps some other forces – had it so.

"I had the impression that this was a Giro that Moser had to win at all costs," Visentini said on that final Sunday in Verona. "And I wasn't wrong."

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.