The third campionissimo: Francesco Moser and Paris-Roubaix

On Paris-Roubaix day Procycling magazine looks back at the career of three-time winner Francesco Moser

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With a career that included a World Championships win, Hour record and countless classics titles, Francesco Moser also remains one just two riders to have ever won Paris-Roubaix three times consecutively.

This article is taken from Procycling magazine issue 267, April 2020.

Subscribe to Procycling and get five issues for £5/$5/€5 as part of our Spring Sale. Terms and conditions apply.

Perhaps the most impressive exploit in ‘A Sunday in Hell’, Jørgen Leth’s celebrated documentary of the 1976 Paris-Roubaix, turns out not to be the winning move in the race. Francesco Moser has missed the decisive attack by Roger de Vlaeminck and Walter Godefroot on the lengthy stretch of cobbles around the village of Bachy, and makes a huge effort to bridge to the duo, who have escaped with Hennie Kuiper and Marc Demeyer. Behind, Freddy Maertens has fallen off and Eddy Merckx is nowhere to be seen. It’s a key moment.

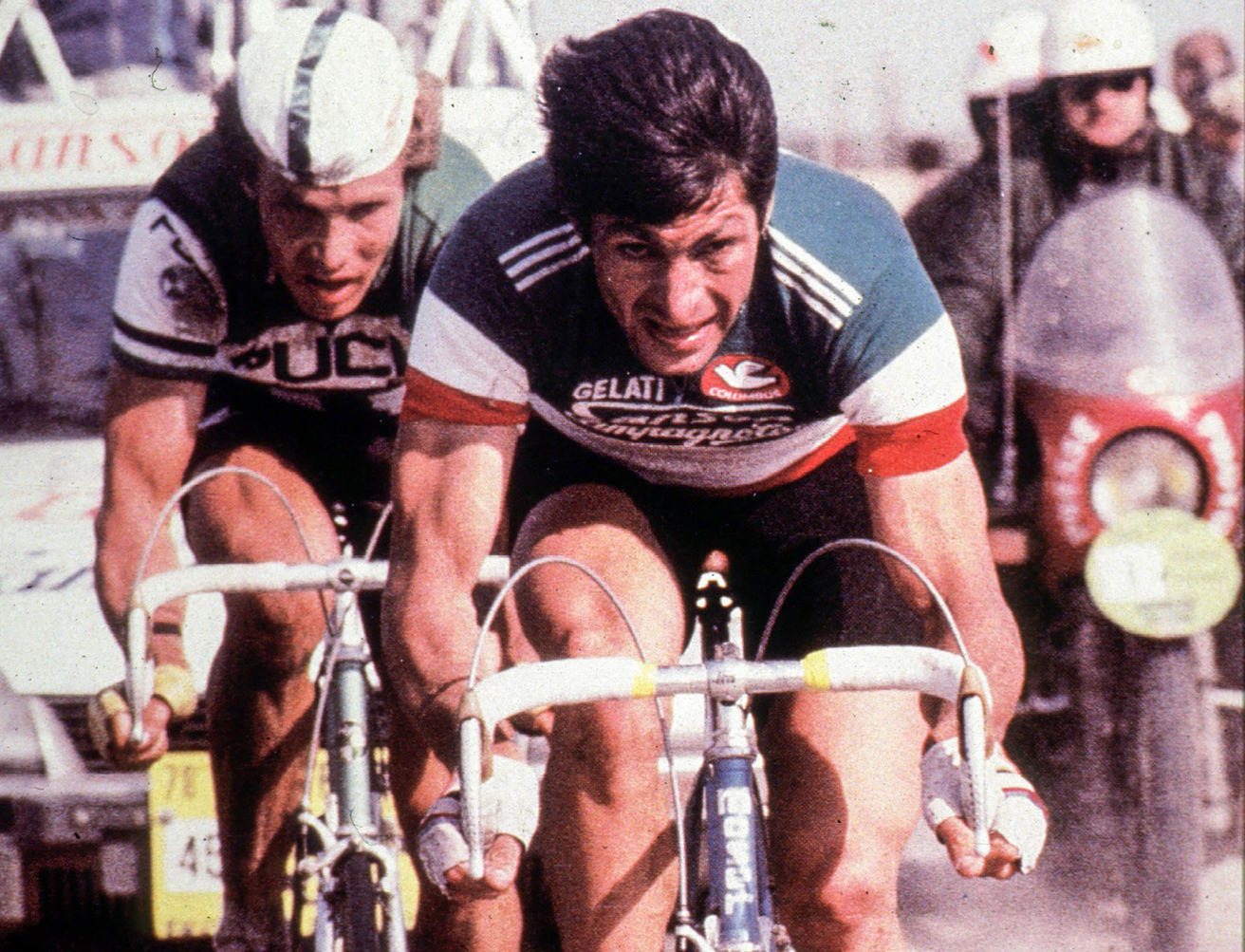

Through the dust clouds, Moser appears in his red, green and white Italian national champion’s jersey, churning a huge gear to fly between two other men who can also sense that it is now or never. The late Raymond Poulidor and the Peugeot leader Jean-Pierre Danguillaume can do nothing as the Italian passes them. Danguillaume makes a brief attempt to latch onto Moser’s wheel, but the pair cannot raise their pace enough. In a flash Moser is gone, “with his distinctive style, his still aerodynamic position on the bike, an imposing sight of almost effortless rotary action,” says the commentator David Saunders, in the English language version of the film.

The burly Italian’s forearms are almost flat, at times parallel with the base of the drop of the handlebars. His back is best described as über-flat - sloping ever so slightly downwards towards the stem. His way of riding as captured in the film by French television cameras - Leth has no in-race camera at this point - is not entirely effortless, in spite of what Saunders states: his shoulders and back are visibly working, and every now and then after leaving the tarmac for the cobbles, the bike is hoicked around or over a pothole in the cobbled gutter.

Moser’s speed is impressive, but even more so is the fact that he goes between Poulidor and Danguillaume, almost brushing their shoulders as he does so - through a mousehole, as the French cycling slang has it. He’s not merely sprinting. His mind is sufficiently clear to make a fine calculation in a split second. He has just enough space to get through that gap and he needs to get through that gap because it is the shortest route to where he wants to get: those back wheels that are a few yards ahead.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The speed and skill are worthy of a Madison rider on the track, but he is doing this with his eyes full of dust. Just before he catches the four leaders, there’s a bend to negotiate; it is taken at speed, again with superb bike handling. The chase lasts over a minute, shown uncut from the moment Moser passes Danguillaume and Poulidor, to the junction with De Vlaeminck and company.

At the start of the film, Moser is introduced almost in passing after lengthy sequences devoted to the two dramatis personae who fascinated the Danish film director most: De Vlaeminck and Merckx. The new great hope sits impassively as his directeur sportif Waldemaro Bartolozzi goes through a basic team meeting (there are cobbles; there will be strong competition) essentially telling his riders that they are hard enough to do the job. “In Italy, Francesco Moser is hailed as the new great hope,” intones Saunders. “At last a new campionissimo who might live up to the glorious past, reminiscent of the great Fausto Coppi.” No pressure then.

Four years later, Moser achieved something Coppi never managed, worthy of a third generation campionissimo, taking Felice Gimondi as the second: a hat-trick of consecutive victories in the Queen of the Classics. Above the Hour records, the wins in Milan-San Remo and the World Championships, it is the most impressive feat of a career that lasted 14 years and included 10 major classic wins (at the monuments, Worlds and Nationals). Only one other rider has ever won Roubaix three years in a row: Octave Lapize between 1909 and 1911.

By 1980, Moser was at the peak of his powers, one of a select group of classics specialists who dominated in the years that spanned Merckx’s decline and immediately after his retirement in spring 1978. He emerged early in the 1970s, from a family of 12 children, based near Trento in the Alpine foothills north of Venice. His elder brothers Enzo, Aldo and Diego all raced as professionals; when ‘Cecco’ turned professional in 1973, at the precocious age of 21, it was for the Filotex team managed by Bartolozzi, with whom Enzo raced.

‘Cecco’ progressed rapidly. He was still a few days short of his 22nd birthday when he won the 14th stage of the Giro d’Italia in his first year as a pro. The following season he added seven Italian one-day races including the Giro del Piemonte and Paris-Tours - a first classic success. More significantly, in 1974, he finished second to De Vlaeminck in his first attempt at Paris-Roubaix, coming into the velodrome well clear of a small chasing group containing Marc Demeyer and Merckx.

“I was just curious that year,” he recalled. “I had a look at a few sections the day before. I fell off in the finale when I was in front on my own; I just braked and flew through the air. But I wanted to do it again. The cobbles didn’t scare me. You can fall off, for sure, but you have to have no fear. You can’t be scared of the other riders, crashes or punctures.”

In 1975 he started the Tour de France,in what would be the only time in his career. It was a resounding success: he won the prologue time trial in Charleroi, he held the yellow jersey for a week, took the stage to Angoulême and rode into Paris wearing the white jersey of best young rider. In the overall standings he finished seventh, a minute behind Italian cycling’s flag bearer Felice Gimondi. Geoffrey Nicholson wrote that ‘Cecco’ brought an exotic “whiff of aftershave from the ski slopes” to the rather utilitarian Grande Boucle, but he would never return. That year he won Il Lombardia and the Nationals, and came fifth at Roubaix and second in San Remo; it was clear that his destiny would lie in the classics and in short time trials, not in the high Alps in July.

Wearing the tricolor jersey, Moser finished second in the 1976 Roubaix, surging past De Vlaeminck in the wake of Demeyer. The following year he was powerless as ‘The Gypsy’ took revenge on the whole cycling world for his bitter defeat of the previous year; he was one of a 19-rider chase group - 14 of whom were classic winners at one time or another - that proved unable to rein in the flying Brooklyn leader. De Vlaeminck’s fourth win cemented his status as ‘Mr Paris-Roubaix,’ but another great specialist was in the wings.

“For a rider to go well in Paris-Roubaix, you need various qualities to come together,” said Moser. “The first is that you need to have the power that it takes to get through a race of over 250 kilometres, where fatigue and pain rip the peloton to shreds as the efforts over the first pavés make themselves felt. They often use the term warrior to describe specialists in the Hell of the North, and that’s because you need a huge amount of courage to take this race on. There is no place for fear on these roads.”

As Leth saw it, both De Vlaeminck and Moser had ‘a kind of x-ray eye that enabled him to read the pavé better than almost anyone else’ - but whereas De Vlaeminck built his victories in Roubaix on his cyclo-cross skills, Moser was in a different register. The muscled shoulders and bulging biceps gave him the ability to produce vast power. He had sufficient pure speed over a few minutes to win the world pursuit title in 1976, and bike handling and race reading skills which enabled him to win the odd six-day. Think Fabian Cancellara, but with sufficient souplesse and adroitness to shine in a Madison.

Moser arrived in Compiègne on April 12 1980 with the favourite’s tag. He had scored two solo wins in the last two editions, each time ahead of De Vlaeminck. For 1978, his Sanson team had hired ‘The Gypsy’, who, to his chagrin, had no option but to look on and ride defensively after ‘Cecco’ - resplendent in the rainbow stripes he had won in Venezuela the previous August - attacked at Carrefour de l’Arbre to join Fausto Coppi and Felice Gimondi in the ranks of Italian winners in ‘Hell’. The following year, De Vlaeminck had transferred to rival ice-cream company Gis; in dry conditions, De Meyer and Kuiper launched the winning move, with De Vlaeminck and Moser linking up. All four would puncture; Moser was fortunate to do so last, when the other three were trailing by 30 seconds.

Earlier in the spring of 1980, Moser had dominated Tirreno-Adriatico, taking the prologue and then taking full advantage when De Vlaeminck - looking for his seventh victory in the race - was penalised two minutes for an illegal bike change. At Milan-San Remo he had been surprised by the diminutive sprinter Pierino Gavazzi; at the Tour of Flanders he had been the dominant force, attacking on the Koppenburg, escaping with Michel Pollentier and Jan Raas in the finale, then responding to six attacks from Pollentier, who finally eluded him on the seventh.

The 1980 race was run off in dry, dusty conditions similar to 1976. De Vlaeminck was fading slightly by now and a new generation was emerging: Sean Kelly, Jean-Luc Vaendenbroucke, Didi Thurau, and most notably a brash young Frenchman named Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle. It was Thurau who forced the initial selection a massive 90 kilometres from the finish, with Moser, Duclos and De Vlaminck on his coat tails along with the young Frenchman René Bittinger.

The decisive moves came on the pavé between Bachy and Wannehain. Moser had constantly forced the pace, pushing his companions to the limit. De Vlaeminck punctured and then crashed as he chased back, prompting Moser to push harder. Duclos had already fallen on the same corner where De Vlaeminck would taste the mud in a few seconds, and shortly afterwards, Moser pressed on ahead of Thurau.

As well as becoming the first rider in the modern era to manage a hat-trick of Roubaix wins, Moser had managed a record average speed of 43.105kph for the ‘new’ course through Hell - Rik Van Steenbergen and Peter Post had gone faster, but on a route with fewer cobbled sections - and behind the margins were impressive: Duclos at almost two minutes, Thurau at 3:30, Hinault six minutes behind in fourth place. “A huge exploit, but not exactly a surprise,” was the verdict of one seasoned onlooker, the writer Jean-Paul Ollivier.

The French were more excited by the emergence of their new star Duclos-Lassalle. His story illustrates Moser’s way of racing, which was that adopted by De Vlaeminck and Merckx: no waiting, just drive as hard as possible and force the opposition to crash or puncture. “I could see that Moser was going to blow the race apart, so I told myself I had to follow him as far as I could; that was how I ended up in the lead four,” Duclos-Lassalle said. “Moser attacked twice, but with no success. He was using a huge gear: I would explode if I rode a gear as big as that, so like De Vlaeminck I had a 46 tooth chainring at the front.”

Duclos-Lassalle’s first crash came after he had bent his back wheel and loosened his back brake; coming up on a corner, he couldn’t brake fast enough. He pulled Moser and Thurau back to within 150 metres, then punctured. Finally, having had a wheel change and overtaken Thurau, he was in hot pursuit of the Italian when he hit the deck again. Meanwhile, Moser was powering away in that perfect style of his; it would take Duclos-Lasalle another 12 years before he finally took victory in Roubaix, then a second win the following year, by which time ‘Cecco’ was happily retired.

In 1979, on exchange at a Breton family home and learning to talk French, I watched Moser’s 1979 Roubaix win live on French television. When you are an impressionable 14-year-old these things are never forgotten; it was the first of zillions of hours I have spent taking in cycling on the small screen. Eight years later, I was at a circuit in the small Venetian hinterland town of San Donà di Piave. The main draw was the world champion Moreno Argentin, sporting a truly foul rainbow jersey with the colours blurred together, giving the impression you were drunk, had a migraine or both.

By then ‘The Sheriff’ was riding out his illustrious career, milking the final few appearances for a few extra quid. After 1980 his career faded, then sprang into life with a surprise attempt on Merckx’s ‘unbeatable’ Hour record in 1984. Moser’s rivalry with Giuseppe Saronni had never hit the heights of Coppi and Bartali despite the Italian media’s persistence in fanning the flames; with both men past their best, it had reached a sterile phase. Five years later though, when I visited the Moser winery and bike showroom for an extended interview, it was noticeable how exercised ‘The Sheriff’ became when I merely mentioned his erstwhile rival.

A few years earlier, I had already drunk a fine Chardonnay from the bottle with the picture of Moser on his wacky disc-wheeled low profile bike and the magic figures 51.151 (his Hour record distance) on it; in his vineyard, Moser posed with a pair of truly ferocious dogs. He still had that aristocratic look that set him apart from the more pugnacious and earthy champions such as De Vlaeminck and Hinault, a patrician confidence that was light years away from the insecurities of former greats such as Freddy Maertens, or the fragile ill health of Walter Godefroot.

Moser remains one of the greats, with a victory tally that exceeds that of De Vlaeminck or Hinault. His all-round palmarès stands the test of time, despite his confession that his Mexico Hour record was assisted by bags of blood that were flown in specially for the occasion - the practice was not illegal at the time - and in spite of his association with two dottori who later gained a certain degree of notoriety: Michele Ferrari and Francesco Conconi. Better to remember Moser as one of Jørgen Leth’s Paris-Roubaix specialists with x-ray eyes, a man who devoured the pavé with strength, courage and consummate aplomb, never more than on April 13 1980.

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world’s toughest sport. Pick up your copy in all good newsagents and supermarkets now, or pick up a Procycling subscription.