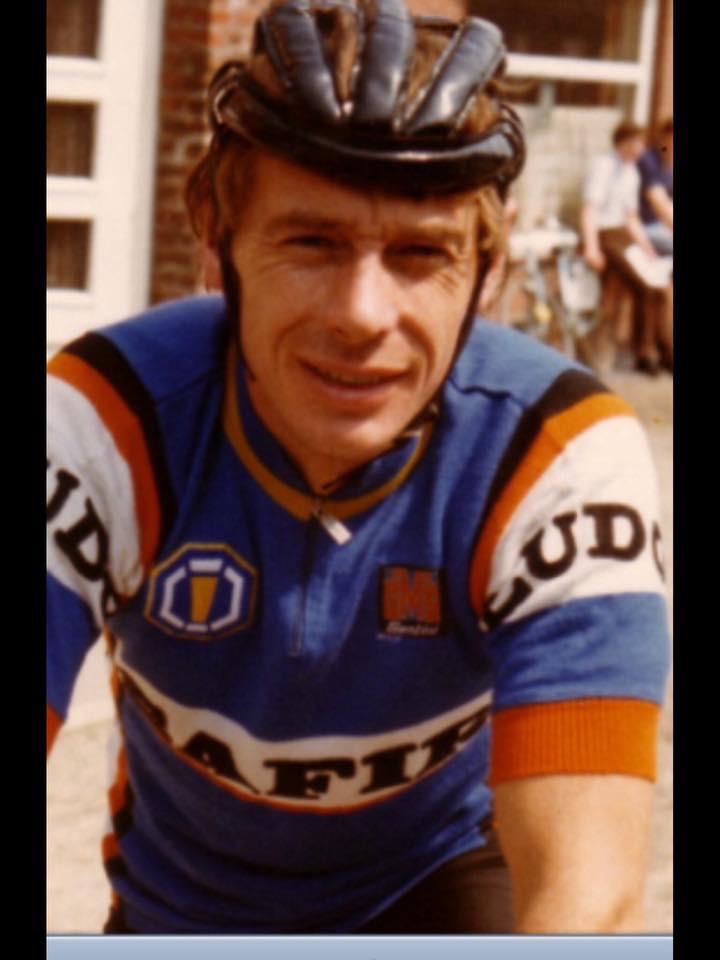

The Smoking Kangaroo: John Trevorrow and the 1981 Giro d'Italia

'Gianni Savio offered me a deal to come over and ride the Giro, so I said OK'

Same bike race, different worlds. Giuseppe Saronni warmed up for the 1981 Giro d'Italia by winning eight races in the opening months of the season and placing second at the Tour de Romandie. John Trevorrow arrived in Italy for his Giro debut after spending more than two months off the bike and then trying to trash himself into a semblance of shape by racing three kermesses in quick succession in Belgium.

Trevorrow's best result in that Giro came right when his form was at his worst. The event can follow a brutal logic of its own. On the third day, and still several kilos away from his racing weight, the Australian's natural speed carried him to sixth place in a bunch finish in Ferrara. He even flashed past Saronni – a year ahead of the fucilata di Goodwood – in the finishing straight, but he had too much ground to recoup on the stage winner Paolo Rosola.

"I was sprinting down the outside and then they closed the door on me," Trevorrow tells Cyclingnews over the phone from Geelong. "I had to sort of stop and go again. I remember passing Saronni and a couple of other very good sprinters at the end. I was gaining but I couldn't get there. And that was the closest I got to a stage win."

Trevorrow, of course, shouldn't have been at that Giro at all, at least in the mind of Safir-Galli directeur sportif Florent Vanvaerenbergh. The Belgian outfit had been hit by an injury crisis that spring and needed a fast man to complete their Giro roster. The head of Galli components, one Gianni Savio, told Vanvaerenbergh that he had just the man. Vanvaerenbergh doubtless expected to be furnished with an Italian sprinter for the corsa rosa, but when Savio sifted through his Rolodex, he was searching for the number of a man from the other side of the world, a rider he had come to know three years previously.

Nowadays, talented Australian riders travel to race in Europe as soon as they are able, with the express aim of building a career on the Old Continent. In the 1970s, however, the domestic scene on road and track was strong enough for men like Trevorrow and Olympic silver medallist Clyde Sefton to spend the bulk of their careers racing at home.

"You didn't earn any more over in Europe than you did in Australia, because our pro set-up allowed us to race and work at the same time. I had a bike shop and it was hard to get away from that," says Trevorrow, whose later work as a race promoter and journalist made him one of the chief architects of modern Australian cycling.

The three-time Sun Tour winner's career as a rider nonetheless featured several stints in Europe, including in the summer of 1978, when he made Savio’s acquaintance while riding for the Carlos-Galli squad. Mercifully, the friendship proved more durable than the componentry.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"At the Worlds around the Nürburgring that year, I was one of only 20 riders left when Francesco Moser attacked. I was really going well, but the next thing I know, my gears start jumping. I look down and both my jockey wheels fall out. Bloody Galli! It was the worst equipment…" Trevorrow laughs. "But Gianni was a good bloke, and I had a contract with the team the next year, too, but I ended up staying in Australia."

When Trevorrow took Savio's call in late March 1981, however, he hadn't been astride a bike in more than two months – not since he had combined with Paul Medhurst to win the Melbourne Six Day in January. In those days, an Australia-based professional's year was punctuated with periods where the demands of family life and the day job had to take precedence over riding a bike.

"In February and March, I hadn't done anything at all, so I was carrying weight and I wasn't fit," Trevorrow says. "Gianni asked me if I was racing and I said, 'No, but that's all right, I'm fit.' Of course, I wasn't fit, I was fat… But Gianni offered me a deal to come over and ride the Giro, so I said OK."

The prize for winning the Melbourne Six that year had been a pair of airline tickets to Europe. Medhurst had no use for his, and so Trevorrow brought his wife Kaye and four young children to Belgium ahead of the Giro, renting a house in Knokke on the North Sea Coast. Another Australian pro – the late Gary Wiggins, father of Bradley – was based in Ghent and a regular visitor.

"My little bloke and Bradley were both less than a year old at the time, and I can remember Brad was like a little steam train even then," Trevorrow says.

Trieste

The atmosphere was rather less hospitable when Trevorrow linked up with his new directeur sportif Vanvaerenbergh in Trieste before the start of the Giro. The team truck had broken down on the way from Belgium, which meant he had to ride the prologue on the spare bike of teammate Willy Sprangers. Vanvaerenbergh, meanwhile, made no secret of his displeasure at the new signing's condition.

"He'd had another Australian, Donny Allan, at Frisol, and he was used to Donny, who was a real professional," Trevorrow says. "He took one look at me and he said that I wasn't fit and I was taking the piss. And I wasn't helped by the fact that Gianni had overruled him and said, 'No, this guy is good, you should take him.' He was looking at me and thinking, 'What the bloody hell have we got here?'"

Vanvaerenbergh's view dimmed still further when he caught Trevorrow at the hotel one evening with a cigarette in his hand, and he complained to Savio in the most forthright terms. After a gentle lecture, however, Savio saw no need for disciplinary action and instead sensed a marketing opportunity.

"Gianni came to me and asked what was going on, so I said, 'I was having a smoke for my nerves, Gianni,' although I actually really was a smoker, which was stupid," Trevorrow says. "So Gianni went to a cigarette company and did a deal, and I got $500 to smoke a cigarette at a stage start, and they paid off a cameraman, who zeroed in on me at the start while I'm puffing away, and then I butt it on the stem and away I go. La Gazzetta dello Sport called me 'The Smoking Kangaroo' when they interviewed me, and I became famous for all the bloody wrong reasons on that Giro."

The performance in Ferrara offered an early boost to Trevorrow's confidence but his lack of base miles meant that he struggled as the Giro made its way along the Adriatic coast and then across to Reggio Calabria in the opening 10 days. The second of the race's three rest days came after three rugged stages in Italy's deep south and offered welcome respite.

"By the time we got halfway through the race, I thought I wasn't going to get through it," Trevorrow says. "I remember the rest day came right at the right time. I never got out of bed; I made them bring my meals into me."

As the race headed back northwards, however, Trevorrow's form began to improve. It helped, perhaps, that the gruppo was governed by two patrons. Saronni and Francesco Moser were divided by a fierce rivalry but united in wanting to impose a certain order to the day's proceedings. Most days on the Giro, there was a tacit understanding that there would be a cap on intensity until television coverage started.

"Piano, piano, they'd say. And, seriously, there's no way I could have finished that Giro if they'd ridden it like they do now," Trevorrow says. "The piano allowed me to ride myself in a bit. There were still some days when it was all on from the start, but on the average day, while you weren't just rolling along, it would start at a good pace. Then the TV would start up, and it was almost like you'd flick a switch and hit it with all you had."

Trevorrow enjoyed some notable cameos later in the race, including one afternoon spent chasing the day's break in the company of Didi Thurau, and by the time the Giro reached its denouement in the high mountains, the Victorian had built up enough a head of steam to survive the most inhospitable of terrain. Giovanni Battaglin famously snatched the maglia rosa on the Tre Cime di Lavaredo thanks in part to his decision to install a triple chainring in anticipation of its brutal final ramps, but there was no such luxury for the men grinding up the mountainside in his wake.

"The small ring was a 42 and the biggest cog must have been about a 26 or something, so you couldn't spin, and it really killed your legs," Trevorrow says. "The Tre Cime di Lavaredo was two days before the finish and that was bloody hard. It nearly killed me. But at least I was coming into a bit of form by then. If it had been in the first week, I wouldn't have got through."

Battaglin's overall victory in that year's Giro – 38 seconds ahead of Sweden's Tommy Primm and 50 up on Saronni – secured only the second Giro-Vuelta a España double in history. The feat was made all the more remarkable by the fact that only 48 days separated the start of the Vuelta in Santander on April 21 and the Giro's conclusion in Verona on June 7.

By then, Trevorrow had earned himself a crack at a similarly arduous double. Vanvaerenbergh selected him for the Safir-Galli team for the Tour de Suisse, which began just 72 hours later after he completed the Giro in 81st place overall – just the third Australian to complete the race after Garry Clively (1976) and Shane Bartley (1979).

"It was almost like doing a five-week Grand Tour," Trevorrow recalls.

He was already thinking ahead to that Swiss challenge when the curtain came down on the 1981 Giro with a time trial that finished in the Roman amphitheatre in the heart of Verona. Before the 42km test, Vanvaerenbergh had one final instruction for his Australian charge.

"He came up to me and he said: 'Just cruise. Make it like another rest day because we've got Switzerland in a couple of days,'" Trevorrow says. He more than took him at his word. "So I did that – I just cruised. And then he said to me afterwards, 'When I said just cruise, I didn't mean for you to cruise like that…'"

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.