The science behind the Landis case

A look inside the defense against the Tour de France winner's testosterone positive

Floyd Landis has been on the defensive since news of his positive dope test was leaked just following the Tour de France. He's been tried in the court of public opinion, but now that he has the data from the test, he's taking the facts of the case to the people. Making his case public could be a telling preemptive strike for Floyd Landis and his legal team as they prepare for the battle ahead. But how sound are their arguments? Laura Weislo analyses the controversial dope test that allegedly showed Landis used testosterone during the Tour de France, as well the Landis team's legal strategy.

The stakes are high in this battle to clear a rider's name, save his career and the yellow jersey he won at this year's Tour de France. The decision to publish extensive documentation last week outlining their case is also a counter to the successive leaks and judgments handed down by senior sports administrators that have had Landis and his head counsel, Howard Jacobs, playing catch-up for weeks after the positive dope test was leaked to the press before Landis was officially notified of the result.

Now they have started to court public opinion as they prepare for hearings they want opened to the public. If granted their wish, the hearing could be standing-room only, as it seems that thousands of cycling fans and anti-doping advocates are devoting massive amounts of their free time to reading and discussing the documentation of this case, poking holes both in the WADA data and the Landis defense.

If anything, the Landis team's decision to publish a PowerPoint presentation of their legal argument, among other documents, has provided a rare view into the intricacies of sports drug testing. This move, referred to by some as the "Wikipedia defense", takes advantage of the high visibility of the athlete and the public's appetite for real information on these doping cases that are seriously undermining the sport's credibility.

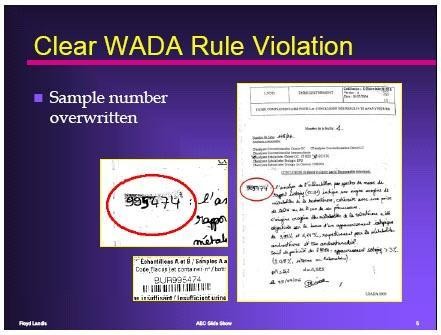

Sample identification issues

The centerpiece of the Landis team's approach is a slide show assembled by longtime Landis friend and retired physician, Dr. Arnie Baker. It outlines a number of problems with the test data, beginning with calling into question the identity of the samples tested. WADA rules state that "Any forensic corrections that need to be made should be done with a single line through and the change should be initialed and dated by the individual making the change." This is a standard quality assurance practice in clinical and pharmaceutical laboratories, called 'Good Laboratory Practice'. "No white-out or erasure that obliterates the original entry is acceptable."

The Landis argument: One of the occurrences of Landis' sample ID is allegedly handwritten over correction fluid, in clear violation of the procedure. There are several other instances where the sample ID number is written illegibly or incorrectly, calling into question the lab's ability to correctly identify the samples they were testing.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The analysis: Internet bloggers generally agree that the lab documents are sloppy, but that this is not enough to clear Landis. The failure to follow lab procedures for document corrections is a serious quality issue for the Chatenay-Malabry lab, but Landis' team isn't arguing that the samples tested weren't his. However, it was a lab screw-up that even WADA chief Dick Pound admits allowed Tyler Hamilton to keep his gold medal from Athens 2004. Labs are run by human beings, and mistakes are bound to happen, but the mistakes in this case are relatively minor when compared with the freezing of Hamilton's B sample.

Testing the testosterone test

Testosterone, like EPO and human growth hormone, is a substance that occurs naturally in the body, making the determination that an athlete has been illegally supplementing with pharmaceutical versions of this chemical very tricky. In the testosterone test's 20 year history, the threshold for a non-normal result has been lowered twice. Initially set at 10:1 testosterone:epitestosterone, it was lowered to 6:1 after research studies indicated that this was an acceptable level. In 2005, the bar was lowered to 4:1. Note that an initial screening of a sample does not, contrary to popular belief, confirm a positive test. Because high T:E ratios can be part of an athlete's normal physiology, further testing is performed on every sample over 4:1 to determine if illegal supplementation is indicated.

The Landis argument: Floyd Landis' initial T:E ratio initially measured as 4.5:1, just over the new limit.

The lowering of the ratio is somewhat controversial. Research from the World Association of Anti-Doping Scientists (WAADS), and communicated to WADA, state that the lowering of the T:E ratio has resulted in more work for laboratories with very few additional confirmed 'adverse analytical findings'. Of 955 samples initially screened with T:E ratios in the range of 4-6, only 3 were confirmed. That is only 0.31%. The document states, "Many experts expressed the desire to be provided with more data and information on the rationale behind this threshold of 4:1". At higher ratios, the confirmation rate goes up, however at a 10:1 ratio, the confirmation rate was still only 31%. It wasn't until the ratio was 20:1 or better that more than 95% were confirmed. It is for this reason that an initial abnormal ratio is not called a positive test.

The analysis: Unfortunately for Landis, the board that advises WADA on anti-doping policy recommended that they maintain the 4:1 ratio for 2007, and request additional investigations. Certainly, the ratio is responsible for a lot more lab work for fewer confirmed positives, raising costs while calling into question the efficiency of the methods, but Landis is one of the few who have been confirmed by further testing.

Contamination?

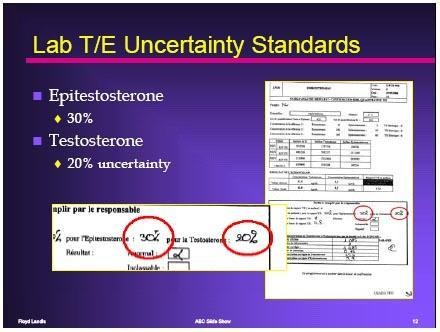

Landis' B sample, which was tested in triplicate using a different method than the initial 'A' sample screen, showed a consistent ratio of 11:1, much higher than the initial screen. However, Baker calls into question the accuracy of this ratio because he says the results show evidence of contamination.

The Landis argument: One caveat to the criteria for an adverse finding can be found in the WADA technical document. It states, "... the concentration of free testosterone and/or epitestosterone in the specimen is not to exceed 5% of the respective glucuroconjugates." This control is in place because there have been some studies that indicate that bacterial contamination can alter the T/E ratios in a urine sample. Landis' team argues that his concentration of epitestosterone is 7.7% of the conjugates, indicating the sample was contaminated (0.44ng/ml epitestosterone without 'hydrolysis', 5.7 ng/ml after hydrolysis - 0.44/5.7 = 7.7% - reference USADA 0283, USADA 0288).

The analysis: It's not entirely clear where in the documents that the lab did the determination of the percentage, or if they did. This calculation was inferred by Baker, and requires more documentation from the lab. There are other indicators of contamination that could be examined, one being the pH of the urine sample. Landis' sample did not have an abnormal pH, throwing the contamination angle into question.

The carbon isotope analysis - is it real? or is it Androderm?

Because of the well established existence of 'outliers' in the population who normally have elevated T:E ratios, the lab routinely follows the elevated 'B' sample with a test to determine whether the testosterone was made by the body ('endogenous'), or if the chemicals come from a man-made source ('exogenous'). The test involves the examination of the carbon isotope ratios of the breakdown products, or metabolites, of testosterone.

The Landis argument: The Landis team argues that the WADA procedure is vague as to whether all metabolites must be out of range, or just one metabolite. The Chantenay-Malabry lab uses the standard that any one of four metabolites coming up 'significantly different' (ie. positive) than the negative control will confirm the positive result. Landis lawyer, Howard Jacobs, said that the UCLA Olympic Analytical Lab which tests for the US Anti-Doping Agency, checks only two metabolites and requires that both metabolites be positive. Dr. Don Catlin, director of the UCLA lab refused to comment on the issue.

Dr. Christiane Ayotte, the director of Canada's doping control laboratory, said that the WADA technical document is very clear on the question, and in drafting the document, 'metabolite(s)' was used to concisely state that if one or more metabolites is abnormal, this confirms exogenous testosterone. "We never imagined that this would be taken in any other way" said Ayotte.

The analysis: The Chantenay-Malabry lab and the INRS in Quebec both agree that any one metabolite showing a significant difference from the negative control indicates a positive test. Dr. Ayotte said that depending on the time the sample is taken after administration of testosterone, the profile of metabolites showing altered carbon isotope ratios will vary, and claims that the science clearly shows that any one metabolite is sufficient to demonstrate exogenous testosterone. If there are varying interpretations of the technical document among the WADA labs, or different procedures in place for exogenous testosterone analysis, this may be enough of a technicality to call the adverse analytical finding into question.

What are the odds?

The vast majority of cases that go to arbitration to argue against dope tests have failed, even if there have been some recent instances where athletes that allegedly tested positive for EPO use - based on the controversial urine test - have successfully had those charges dropped.

Landis could argue for a 'longitudinal analysis' of his urine samples prior to, and after stage 17 of the Tour de France. Could he use all the negative samples before and after stage 17 to say that it would be physically impossible for him to have taken testosterone? Or would he have to establish that he had a borderline T:E ratio naturally?

Precedents count for a great deal in any court, and in this area, Landis may look to Italy's glamour mountain-biker, Paola Pezzo, who managed to successfully defend herself against positive test for nandrolone. She used the fact that samples prior to and after her positive sample were negative, something physically impossible for the slowly metabolized chemical.

What has to be taken into consideration is the nature of this case, and the qualifications and knowledge-base of the people who will determine whether Landis is a cheat, or just an athlete who has been denied justice by some politically-motivated sports administrator. The stakes are high for cycling, but they are equally high for the anti-doping movement, for the labs, and the scientists who run them.

Regardless of the outcome of Landis' case, one thing is for certain, and that it's the sport of cycling that is also on trial. With the importance of this case, and it's impact on the sport that so many fans hold dear, it becomes clear why these fans would spend countless hours on their computers searching for a better understanding of the facts.

Laura Weislo has been with Cyclingnews since 2006 after making a switch from a career in science. As Managing Editor, she coordinates coverage for North American events and global news. As former elite-level road racer who dabbled in cyclo-cross and track, Laura has a passion for all three disciplines. When not working she likes to go camping and explore lesser traveled roads, paths and gravel tracks. Laura specialises in covering doping, anti-doping, UCI governance and performing data analysis.