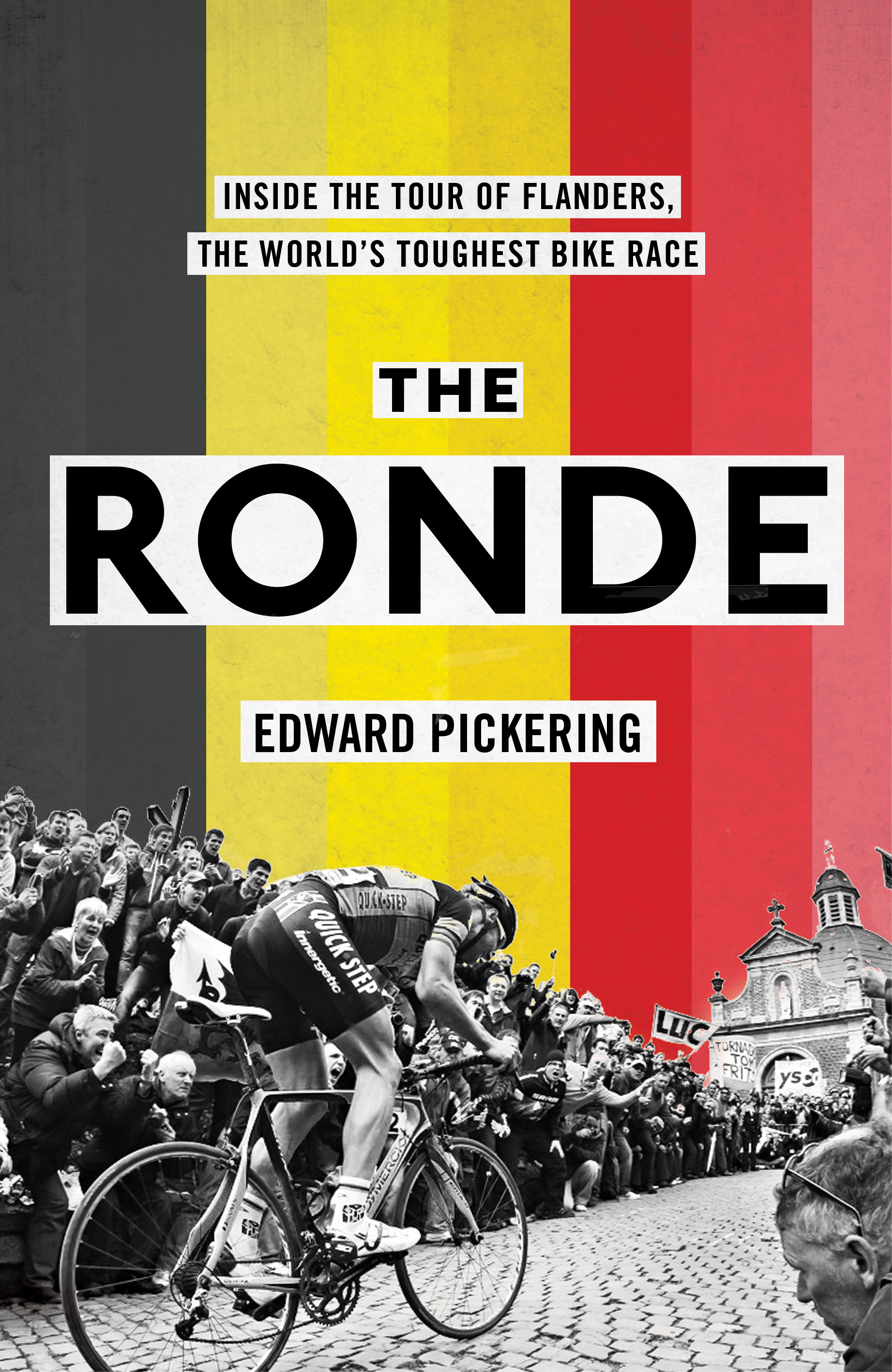

The Ronde: Inside the world's toughest bike race - Book extract

Edward Pickering explores the cultural significance of the Tour of Flanders

The following is an extract from The Ronde: Inside the world's toughest bike race, by Edward Pickering, published by Simon and Schuster, available here. For more from 'Belgian Week' on Cyclingnews, click here.

In some parts of the 'traditional' cycling countries – Belgium, France, Spain and Italy – cycling seems to be an expression of regional pride as much as national pride. Though the internationalisation of the sport in the 21st century is diluting this tendency, by reputation the most passionate fans come from Flanders, Brittany, the Basque Country and Tuscany.

These regions have also produced a surfeit of professional riders, lots of local racing and a large following for the sport, and they remain hotbeds of cycling talent. Bike races held in these regions have special atmospheres, and their fans are extremely knowledgeable about the sport.

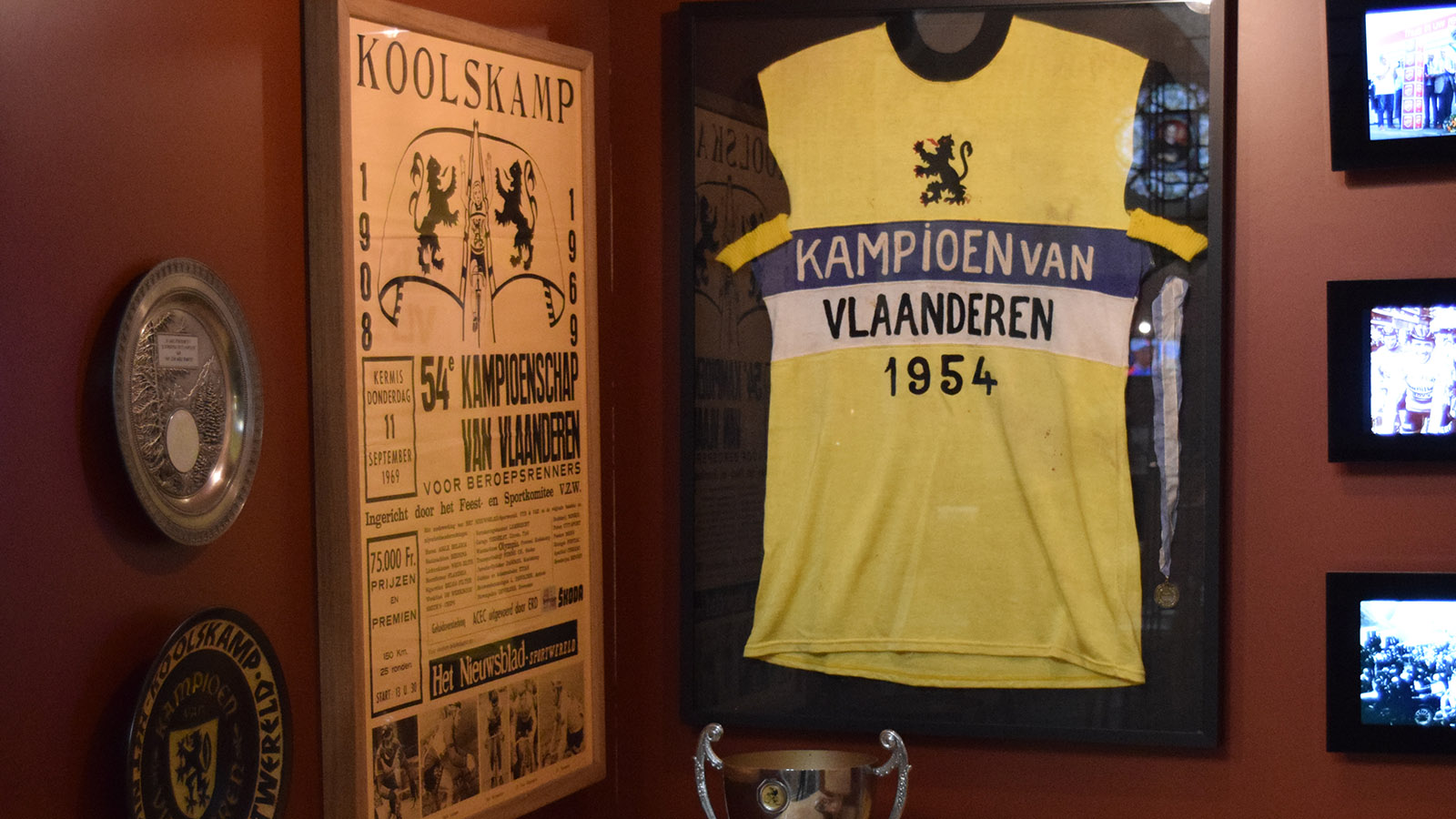

It could be coincidental but the first three regions especially have strong separatist movements. (Also, the Lega Nord political party – which advocates policies ranging between greater autonomy for the northern regions of Italy and outright secession from the south – came second in Tuscany in the last elections in 2015.) One of the defining aspects of bike races in Flanders, Brittany and the Basque Country is the omnipresence of the local flags – the black lion rampant with red claws on a yellow background (black claws for the Flemish nationalists) of the Vlaamse Leeuw for Flanders, the black and white stripes of the Breton Gwenn-ha-du and the red, white and green ikurrina of the Basque Country.

There are similarities between the bike racing in Brittany and Flanders. An almost autonomous circuit of local races evolved in both regions that were linked to local religious festivals. In Brittany, each village held festivals of penitence, known as Pardons, and through the 20th century bike races, usually based on laps of a shortish circuit, became part of the entertainment. The Flemish equivalent is the kermis, a celebration of the local patron saint, where bike races, similarly based on circuits, are often the highlight. In the second half of the 20th century it became possible for riders to make a good career out of participating only in this kind of race in their local regions, with no need to turn professional and participate internationally.

The Ronde is an expression of Flemish culture, and regional identity is at the centre of its importance in Flanders. There's a lot more to this than it being a big bike race that happens to take place in the region. The race was consciously developed as part of a movement known as wielerflamingantisme – literally: cycling Flemish nationalism (the French term 'flamingantisme', which described the Flemish movement, is more often used than the Flemish Vlaamsgezind – the French term was initially derogatory but was adopted as a badge of honour).

The Ronde's founder Karel Van Wijnendaele used the success of Flemish riders between the wars to further promote the cause of Flemish regional pride and emancipation. This was necessary because the Flemish majority had been economically, culturally and institutionally suppressed by the French-speaking minority through the 1800s. But paradoxically it also highlights one of the quirks of the region, that historically Flanders has been an ill-defined entity, as has Belgium, which only came into being in 1830 (though this is earlier than modern Italy or Germany, for example).

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Traditionally, the race has mainly taken place in the provinces of East and West Flanders, yet these are only two of five provinces that make up the modern region of Flanders. Since 2017 the race has started in Antwerp, which is in the province of the same name, and barely touches West Flanders, which is the most cycling-mad province of all. And all this doesn't take into account that in the past, 'true' Flanders consisted only of the provinces of East and West Flanders – Limburg and Brabant were never historically part of the region.

So when we say that the Tour of Flanders is the most important unifying event for its region, what do we mean? To understand the Ronde, you have to understand Flanders and Belgium and what they are and what they are not.

The Tour of Flanders has changed to reflect social changes. At first it was an expression of Flemish potential and then, as local riders dominated, it became proof – along with Flemish victories in the Tour de France from the 1910s onwards – that the Flemish could win. Now, there's less need for the Flemish to prove themselves by winning the Ronde, although they still often do so. The race is a huge international affair, one of the biggest bike races in the world, and attracts fans from all over the globe. Flanders – once a strip of chilly, salty, marshy coastline, and for centuries an inward-looking backwater – has become an international, ambitious, outward-looking region. The race also covers up, but doesn't negate, the background tension that constantly exists in Belgium, a reminder that the country is at once more than and less than the sum of its parts.

I think the Ronde is the best bike race in the world. The Tour de France grabs me in a different way, and the Ronde van Vlaanderen can't compete with its size. But a lot happens in the Tour that doesn't surprise me very much, whereas I can watch the entire six-hour broadcast of the Ronde and, once the hills start, be gripped the whole way. It's hard, tactically fascinating, unpredictable and engaging. Riders have spent entire careers trying to learn and master the twists and turns of the event, even as the organisers change the route either subtly or in major ways every year. And while the current route has tipped the balance a little away from brains towards brawn, the challenge of winning the Ronde still comes down to who can be physically and tactically good, and maybe lucky.

Nick Nuyens told me, 'I realise I was not the biggest rider. I was not the strongest rider. Of course, to win, everything has to fit, like a puzzle'.

The Ronde: Inside the world's toughest bike race, is available here.

Edward Pickering is Procycling magazine's editor. He graduated in French and Art History from Leeds University and spent three years teaching English in Japan before returning to do a postgraduate diploma in magazine journalism at Harlow College, Essex. He did a two-week internship at Cycling Weekly in late 2001 and didn't leave until 11 years later, by which time he was Cycle Sport magazine's deputy editor. After two years as a freelance writer, he joined Procycling as editor in 2015. He is the author of The Race Against Time, The Yellow Jersey Club and Ronde, and he spends his spare time running, playing the piano and playing taiko drums.