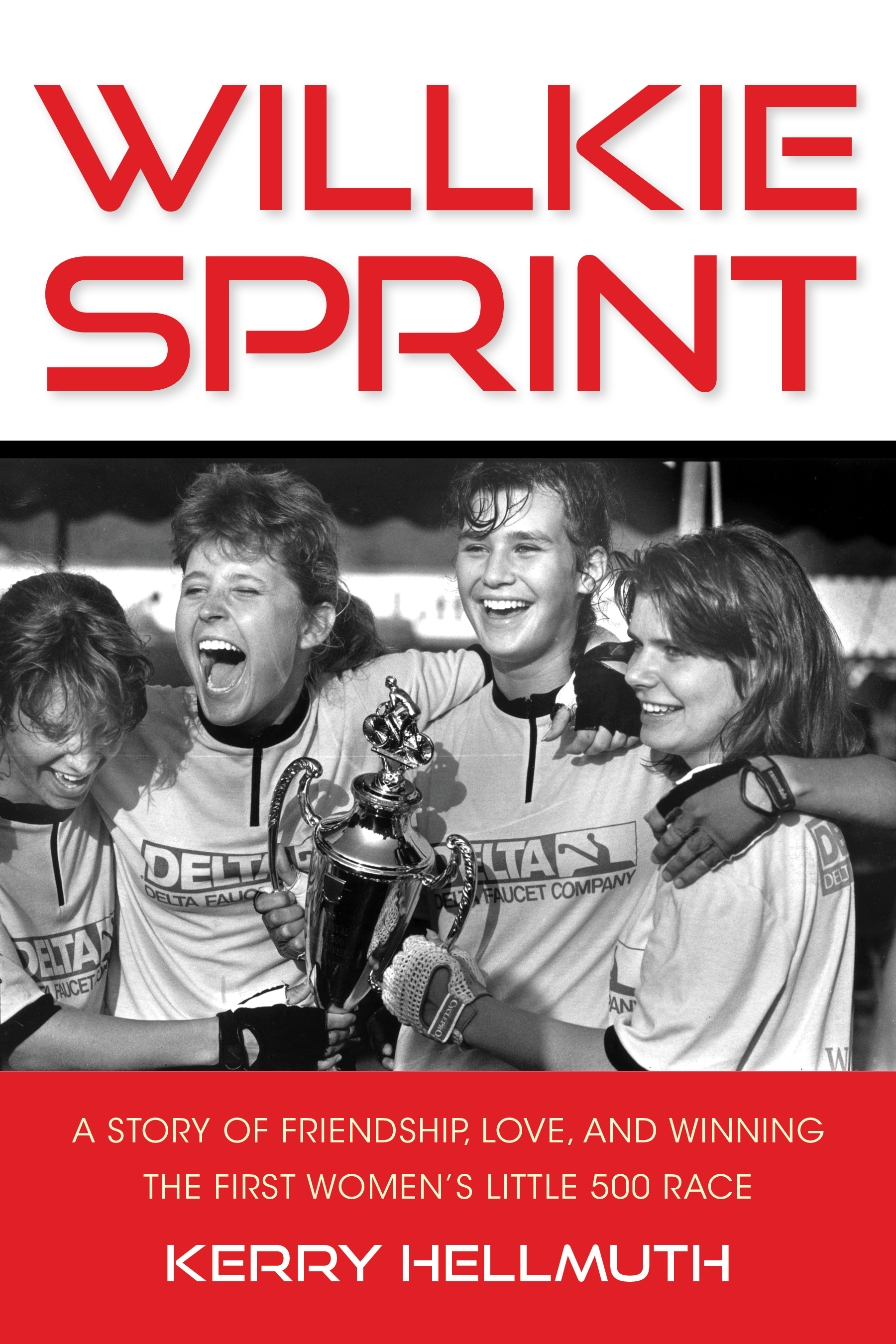

'The perfect underdogs' - How Willkie Sprint made history winning the first women's Little 500

How an all-freshman women's team joined ‘Breaking Away’ lore in 1988 as recounted by team member Kerry Hellmuth in new book Willkie Sprint

Kerry Hellmuth made history in 1988 as a member of the first team, Willkie Sprint, to win the women’s Little 500. Remember “Breaking Away”, the award-winning movie (an Oscar for best screenplay) about a men’s bicycle race on the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington? The local ‘townie' team, The Cutters, were the underdogs and rose to glory. Hellmuth recounts how her all-freshman group went from “scrappy, ragtag team” to “rock-star status on campus” and became “the perfect underdogs” for women.

Hellmuth penned the coming-of-age story about this one year in college life that was much more than learning to stay upright on rollers and how to make a bike exchange in a relay. Her book explains the uphill challenge for women at that time with the slow progress of Title IX of the Civil Rights Act that was passed in the US just a decade before, when women gained access to the same benefits as men at federally-funded schools, including educational and athletic programmes.

But Hellmuth does not use a harsh tone. She tells her story with light humour and an authentic voice throughout the saga of her freshman year. She provides some historical background on early victories in the 19th century for women to just ride bicycles (Amelia Bloomer and a split skirt to ride on two wheels), the movement for women to race road bikes, not tricycles, in the Little 500, and how 1988 made a big difference for more than just the four teammates.

She pointed out that while it was a winner-take-all scenario on the track for the 100-lap race, with blood, sweat, tears and laughs in the months of buildup, it all came down to proving “that women deserved to be given the same opportunities as men” and “the friendships within and between teams were both an added bonus and the most poignant part of the experience”.

Cyclingnews is providing this content as part of a celebration for International Women’s Day. In this excerpt, Chapter 4, Hellmuth describes the team’s first visit to the track where the race will be held in the spring, what types of bicycles they had to use, and the daunting task that lay before them. The official publication date for the book is April 1, with early delivery for orders placed with Indiana University Press. Reprinted with permission from Indiana University Press.

Stepping onto the Little 500 track for the first time was an exciting moment. The Armstrong Stadium seemed bigger than I remembered from my attendance at an IU soccer game months earlier. We had imagined how it might be to ride on the surface made of black cinder.

Now we would finally be able to experience the shifting cinder under the wheels of our track bikes. But not yet. First, we had a bunch of information to take in. Hand signals that we should use, track etiquette that might save you from getting hit by someone sprinting or coming out for an exchange. Where to find the first aid table if you fell and got scraped up or, worse yet, black cinder ground into your wounds.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Where (designated outer lane) and what the rules were for making exchanges. What the stoplights meant. Yes, stoplights. The big oval track had small stoplights in each of the four corners, and the lights gave information about the conditions on the track. Green light meant smooth sailing. If there had been a crash, the riders were “neutralized” with a yellow light, meaning slow down and proceed with caution. That one became a factor on race day. The red light, well, I don’t need to explain that one.

Amy looked at me as we listened to instructions for how to properly move within the pack. “Slower riders have the responsibility to move toward the outside of the track to allow faster riders to pass using the inner lane,” the veteran riders explained.

Amy whispered, “Sheesh! This is crazy!” She raised her eyebrows and flashed me a smile. Then she added, “We’re just gonna have to be faster than everyone so we don’t have to ride in the pack.” Kristin heard her too and laughed.

If you thought about it for a minute, just one sane minute, Amy was absolutely right. Little 500 is crazy. I mean, amazing, yes. But really and truly? A bunch of college kids racing heavy single-speed bikes around an unbanked cinder track, doing these awesome (a fine exchange being true fluidity of motion!) but (let’s admit it) silly exchanges to keep the team’s momentum moving even as they switched riders? Sounds like a recipe for disaster. The whole concept is a bit whacked if you think about it for a moment. So, from then on, I didn’t.

When we were finally set free to ride our first laps, everyone was polite and riding very respectfully, at least for the first day or two. The clinic was led by the Riders’ Council, consisting of the Theta riders and some other women who had raced in the Series’ events during the previous year or were involved with helping organize the whole event and a few of the men’s Riders’ Council members who didn’t really do much. It seemed deliberately designed to put a scare into us rookie riders. And well, I guess that was probably the correct approach. If you didn’t follow the rules of the track, bad things could and likely would happen. See my earlier comments—the whole concept really was a recipe for potential mishaps. When we were cut loose to ride, everyone was very carefully riding the oval, signaling, and calling out their every move.

“Yip-yip-yipee . . . Let the fun begin!” I shouted to my teammates as I finally headed out of our pit and rode my first laps. The track felt great. The cinder was relatively hard-packed, and it felt more stable than the gravel-like feel I had expected. What I did not expect was how much fun riding in a circle could be and how much it could inspire speed. I yelped out a spontaneous “Woohoo” as I flew past our pit after that first lap, trying to remember all of the rules about passing other riders.

It was time to see how riding the track was at high speed. “On your inside!” I called out to riders as I passed them on the left, taking the innermost lane next to the slightly recessed sloping cement gutter. I was so psyched to finally be on the track that I could not resist sprinting across what would eventually be the finish line, at the halfway point of the front straightaway. Kirsten had hopped on our other bike. She joined me for the next lap, and we sprinted against each other across the line, coming in almost dead even. I threw my arms high in the air to celebrate the victory over her, despite being uncertain whether I had actually beaten her.

Willkie Sprint at a practice session

The Roadmaster bicycles that had been issued to each team were not high- tech dream bikes, but they were not as clunky as I had expected. The bikes were, in fact, the opposite of high tech, created by the same brand that made the low-cost bikes available at Kmart and ShopKo, the Walmarts of the day. That, of course, was a financial consideration so the race would be accessible to all. You could change almost all the parts on the bike, although the rules indicated precisely which replacements were allowed.

The Little 500 Manual, referred to as the bible by some, gave the parts’ specifications, rider eligibility rules, rules of conduct for racers and coaches alike, and race regulations—in such exacting detail that it was about fifty single-spaced pages, no kidding! Kevin had returned from a meeting a few months earlier with one hefty copy of it and told us we were all supposed to read it. He shook his head back and forth, saying, “I didn’t know what I was getting into! Look at this thing. I am not sure any of us knew what we were getting into. Girls, this race is serious. Don’t fight over who gets to read this first!” He laughed and tossed it on the table.

Kirsten picked it up, opened it to a random page, and said, “OK, here we go: ‘Illegal recruitment is defined as making cash payments or giving other perks to riders for their services.’ Jeez, we aren’t riding in the Olympics here, people. But, actually, maybe I can make some money next year. Or perks. What kind of perks are they talking about?”

She flipped a few pages and read, “‘Rookie riders must have achieved a minimum 2.0 GPA in the fall semester.’ Uh-oh, anyone out?”

Louise responded, smiling, “No, but it’s a good thing I dropped that chem- istry class or I might have been.”

Kirsten continued, “OK, listen up. The penalties section: ‘One. Failure to observe flags, two seconds. Two. Creeping will not be tolerated. Track position and relative distance to the leader must be maintained during caution conditions signified by the yellow flag.’ Tucker, you got that?” Kirsten said to Amy, accusingly. “No moving up on the sly when the yellow’s out!”

Amy balked, “Wait. Why are you telling me? I’m no cheater! I win fair and square.”

By the end of that first practice, I was exhilarated from endorphins, effort, and excitement. The track was surprisingly smooth and faster than I expected. Within a week or so, I would come to realize that the cinder surface could break down a bit and become like kitty litter, especially when we followed a men’s practice with full attendance. Then, you might feel a little slide or shift, and it was easy to understand how that could freak out riders with less experience or less confidence on the bike, which defined basically everyone in the women’s race.

I could see why Little 500 was famous for its crashes and pileups. I had heard that part of the fun of watching the race was watching breakaway attempts, but the biggest crowd-pleaser was a crash. Let’s face it, for much of the college-aged crowd, the big pile-on crashes provided definite entertainment value. Kind of like the fights in hockey games. I once read that the vast majority of hockey fans like the brawls and actually oppose a fighting ban. Same thing with crashes. Sad fact about humans: we love watching misfortune and violence.

Willkie Sprint teammates model new painted helmets for the inaugural race

... (Clipped for brevity - ed.)

Anyway, that first day the guys practiced after us, so they started showing up in the last ten minutes of our practice. Euphoric and slap-happy after our introduction to track riding, we bantered with them about the fun they were about to experience.

I summed up what they’d experience in the next two hours: “First, they’re going to scare you out of your minds telling you about crashing, telling you how the cinders dig into your skin so deeply that they have to scrub them out with a steel brush in the ER. Then when they finally let you do some riding, you have half the group going super-cautiously slow while the other half is just loving the track and flying. Honestly, kind of a dangerous combo. And definitely ironic after the whole discussion. So, yeah, have fun!”

“Wow. Can’t wait. Thanks for the preview,” said Rob.

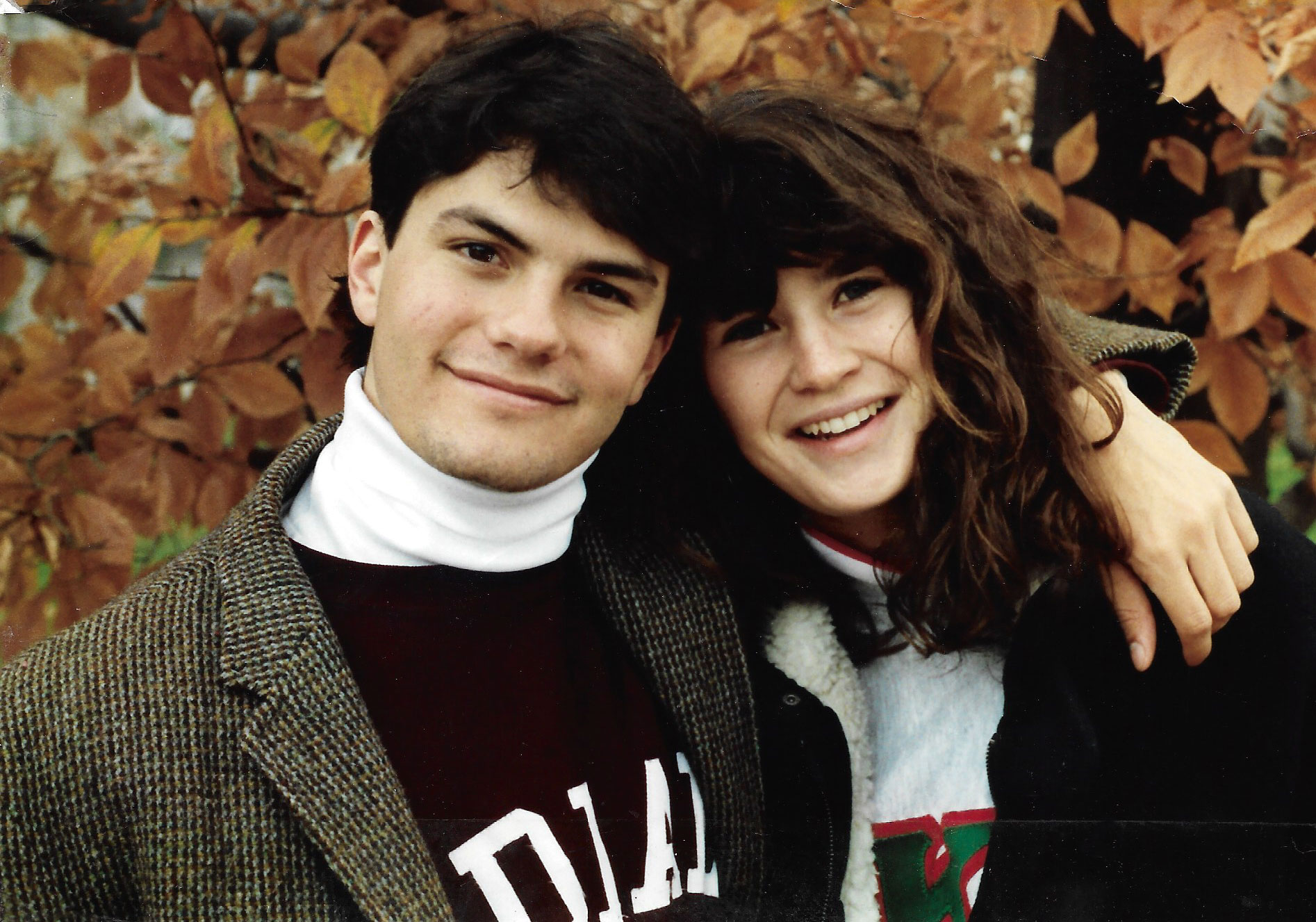

I smiled and admitted, “Actually, no. Seriously, it’s a real blast. Just take the inside line.” I offered to ride Rob’s bike back to the dorm in order to leave them the track bike. It turned out to be the perfect size for me. When I ran into him at dinner a few hours later, he told me that the addition of testosterone to the mix made their practice total chaos.

“Thanks for the tip, but I didn’t take the inside. Didn’t seem too smart,” he told me.

“Glad you used your own little thinking cap then,” I told him.

“Hey,” he said, “about going out for that dinner together. What are you doing Friday?” And just like that I had a date with a nice college guy. I smiled inside and out.