The Greatest: The Times and Life of Beryl Burton – extract

New biography sets out to tell Burton's story in detail for the first time

The world championships in East Germany in the summer of 1960 came at a golden moment in Burton's career, at the end of another spectacular season of domination and self-discovery. Her spring campaign began with a two-week trip to race with a Great Britain selection at the Werner Seelenbinder indoor track in East Berlin. There, Burton was shown by the top British sprinter Lloyd Binch how to ride the 60-degree 'wall of death' bankings – a far cry from the gentle slopes of outdoor tracks such as Herne Hill.

'A wonderful trip,' she wrote, 'with a big reception [every night] where tables groaned under the weight of beautifully presented food.' Not to mention secret service 'heavies' who kept tabs on her and the sprinter Jean Dunn whenever they ventured into the city.

Two weeks' intense track racing in Berlin set Burton up for a rapid spring. As in 1959, she was exhibiting supreme versatility across four disciplines, winning road races solo and competing strongly in the national grass track championship at Tom Simpson's home town of Harworth. Six hours before flying out to East Germany for the World's, she defended her RTTC 100-mile championship, in a new record time of 4hr 18min 19sec, and with an 11-minute victory margin.

There had been some debate with the British Cycling Federation over her participation in this 100-mile title race – it clashed with the team's scheduled travel to Leipzig – but eventually Burton was given special dispensation to fly out to East Berlin and join the rest of the team immediately afterwards, at her own expense. The upshot was another mini-saga; [her husband] Charlie came to meet her at the airport, but her plane was late and they had no way of travelling on to Leipzig that night. Eventually, after wandering East Berlin looking for somewhere to stay, they entered a police station, more in hope than expectation; fortunately, strings were pulled and they were found a hotel paid for by the East German state.

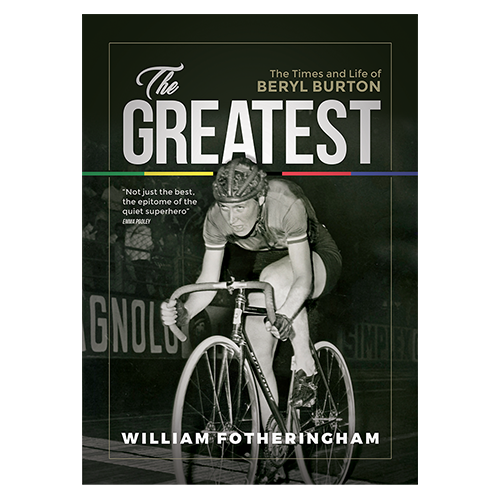

This is an edited extract from William Fotheringham's new biography The Greatest: The Times and Life of Beryl Burton.

The book is available through Islabikes, William Fotheringham's website or Prendas Ciclismo.

The pursuit series on the Leipzig velodrome did not go entirely smoothly. The racing was disrupted by rain, and Burton was fortunate to escape injury when the cone in one of her wheels broke. The British were poorly equipped as usual, and she had to accept the loan of rollers from the Russians. For the final, the GB women's coach Eileen Gray, who knew that Burton appreciated encouragement, rounded up practically every English journalist and rider present with instructions to spread around the track and yell at her as she rode. 'I couldn't help giggling,' said Burton, 'as I came within earshot of each one and heard their frantic shouts.'

Not that hearing can have been easy, with the velodrome packed with 25,000 spectators. Gray also delegated Daily Express journalist Ron White and his wife Cath to shield Burton from autograph hunters, photographers and interviewers as she prepared for her events in the track's centre; she knew that Burton suffered from anxiety and she needed to be protected.

That pursuit series was one of Burton's finest, prompting the editor of Cycling, George Pearson, to compare her with the French ace Roger Rivière: 'She tore into last year's finalist Elsy Jacobs with a power that completely demoralised this very competent performer, beating all known standards in the west with a time of 4min 12.9sec.' That time was a world record, a huge eight seconds faster than her best opponent; she then cut that to 4min 10sec in the quarter-final, and improved again to 4min 6.1sec in beating Marie-Thérèse Naessens in the final.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In the road race, Burton went almost unchallenged on the tough five-mile Sachsenring circuit, this time in front of a crowd of 65,000. Pearson's report described her as 'immeasurably superior to any other woman cyclist on the road…' Having responded to an attack from Elsy Jacobs on the fourth lap, Burton then set a pace that suited her. She turned round and looked at the 1958 champion, who simply shook her head; she could not follow. With Jacobs back in the peloton, and Burton's team-mates shadowing counter-attacks, the race turned into a replica of the time trials she rode every weekend in the UK.

Burton did not particularly like road racing, but felt she had no option but to ride road races because there was a chance for a world title; had there been a time trial world championship, she probably would not have bothered. Charlie's take on her tactical approach is amusing: 'She had no more tactics than that Christmas tree. If she road raced she'd get to the front, get stuck in and drop them on the first stretch; if someone sat on her wheel she'd just get on with it. She just went. And when she went, she went.' Burton had a simple strategy: wait for a hill, ride up it as quick as possible, and hope to end up on her own at the top.

Under the headline, 'Beryl Toyed with Them', Pearson described her opponents as 'a world championship field that was permitted to look effective only until the champion was ready to take command.' Her winning margin was a massive 3min 37sec, carved out in just 20 miles.

Leipzig gave Burton two of the three world titles available to women, crowning her as the strongest in the world. She did not, however, rest on her laurels. There were track meetings and time trials in the UK, and finally a trip to Milan – financed by a hurried fundraising drive in [her home town of] Morley – for an attempt at Jacobs' Hour Record on the mythical Vigorelli velodrome.

The Vigorelli, at the time the fastest track in the world, is partly open to the elements, which means that warm, dry weather is needed for any record attempt. The Burtons endured continual heavy rain and wind, and even snow. The first attempt, on 5 October, fell flat after half an hour; a second bid shortly afterwards saw Burton break Jacobs's 20km record but come up 500 metres short after the 60 minutes, a significant margin in an Hour Record. She and Charlie went home, looked at the remaining money from the donations, and decided there was just enough for a second trip if Beryl went solo. But the weather remained against her, and she spent another frustrating spell sitting in a hotel waiting for it to clear: she did not turn a pedal in earnest. It was the first major setback of her career.