The father of freeride

The term legend is used frequently in the sport of cycling. Sometimes it's warranted, sometimes not...

An interview with Hans Rey, April 15, 2006

The term legend is used frequently in the sport of cycling. Sometimes it's warranted, sometimes not - but one thing's certain - the development of freeriding owes a lot to mountain biking legend Hans 'no way' Rey. Cyclingnews' Steve Medcroft caught up with this German freespirit to find out a little more about his legacy in the sport and how he's using it for the future.

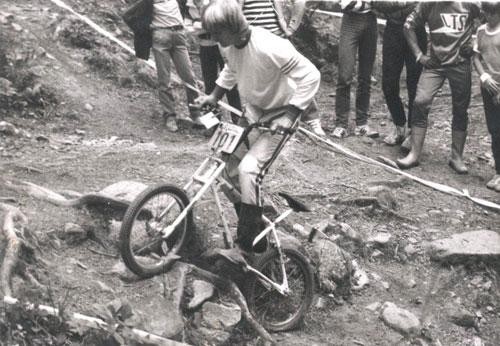

Hans Rey didn't start out his career planning to found the freeride branch of the mountain-biking tree. In fact, the charismatic German didn't even plan to be a mountain biker at all; he had a fully established career in the prominent amateur European sport of trials. Both on motorcycles and bicycles, Rey could balance, pivot and hop as well as anyone, pocketing a number of national championships in his early career. But when mountain biking exploded in the US and Rey learned that riders near his skill level were making a living competing in trials, he moved to southern California's beach communities and dominated the fledgling American sport.

When the popularity (and opportunities) in trials dwindled, Rey had the inspiring idea to take his mountain bike on Indiana Jones like adventures and bring a camera crew along to catch whatever happened.

The resulting DVD's and feature television documentaries have made Hans Rey synonymous with insane freeride adventures in exotic places and sparked the imagination of a thousand riders to follow in his footsteps.

Today, Rey produces one or two adventure trips a year, performs trials exhibitions around the world, and is focused on his charity; Wheels 4 Life, which buys bicycles for health workers and needy people in third-world countries.

We caught Rey jumping his bike over spectators at the Tour of California.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Cyclingnews: You've been spotted doing trials shows at the Tour of California, how did that come about?

Hans Rey: Clif Bar, who sponsored the race, asked me to come to some of the stages and entertain the crowds – especially at the finish lines before the races ended. I did a couple of shows including one at the final stage at Redondo Beach. We have some obstacles we haul around on the trailer so we set up a little course and pumped up the crowd with some music.

CN: How far in advance are you scheduled for events like this or do you stay pretty loose?

HR: I stay pretty loose. That's how you have to do it. I have no problem scheduling certain things, like the adventure trips, but generally I leave time and space open. Which means I have some things booked for as late as November but I was able to do this on short notice.

CN: Many of your adventures are televised. How vital is television to your career?

HR: TV is very important. It's what I've focused on for the last ten years. TV is the reason that I'm still around, the reason for my longevity. People wonder why a guy who's 40 is still sponsored and doing what he does, and the reason is that I generate a lot of media exposure which, ultimately, is what the sponsor wants to get out of me. My adventure team trips are always made for TV, for example. They end up as thirty to sixty minute documentaries that even air internationally – in like a hundred different countries on one channel or another. When I do the trips, I'm aware of what will be interesting on television. I treat them more like an expedition. I try hard to not just go to a pretty place and hop around on my bike. I try to accomplish something. I'm usually in search of something historical or mysterious.

CN: You try to have enough story lines that the final programme can be tailored to the outlet who ends up running it?

HR: Exactly. And I like that part of it. I like doing the research, finding the story lines that make sense when combined with biking. Whether it's our trip to the Pyramids or China, I'm happy with what we've done. We get good feedback. Even my girlfriend – who doesn't like cycling much – watches the whole show when it's done. The reason is that its not just about cycling.

CN: Is this still a speculative venture for you – do you put together the trip with no definite TV deal?

HR: I try to get a deal first but sometimes we spec it. I spec'd maybe my best trip ever – the one with Richie Schley to East Africa [2004's Mountain Kenya Rage during which the pair's goal was to be the first to summit and traverse Mt. Kenya in Africa (16,300ft) on mountain bikes]. It was a full-on first ascent and a full-on expedition.

CN: Have you pitched your work as a series to any of the networks?

HR: We haven't had success with that. We've pitched it here and there but the TV world doesn't really know what it wants. Right around the time when these reality shows became popular, the TV world decided that adventure shows were out. Then came a time when everybody in TV compared what we did to adventure racing. There's a big difference. But what can I do? Once the TV world decides something is out, it doesn't matter that they don't research it it's just out.

CN: Do you tweak your work to try and catch the next popular TV wave or do you believe that what you do will just cycle back in popularity?

HR: A bit of both. I'm trying to stay true to what I set out to do but I also want to be flexible and open to new experiences. I admit that what I do is nichy and obscure, and TV people like to fabricate things so I just don't fit all the time. I mean, look at the Olympics. They don't care about the 25% hardcore athletic viewer; they want to get the other 75% - who don't care about sports. In the end they come up with a product that doesn't work for anybody. But it's all relative. There are too many channels now. In Germany, when I grew up, there were only three channels; nowadays, there are more channels than any person could ever watch. I wouldn't recognise anyone who's on MTV, for example. And I know it's huge with certain demographics. There are many more opportunities for us to find a home.

CN: What adventures do you have planned this year?

HR: The promoter of the biggest festival in the Philippines [the Terry Larrazabal Bike Festival (March 30 - April 2) in Ormoc City] approached me to help promote the event. It has every sort of cycling in it from a UCI road race to dirt jumping, BMX, mountain biking and family fun rides. It should be a nice one or two day trip.

CN: How long have you lived in Laguna Beach?

HR: Since 1990 or so. I came to the States in 1987. Even though I lived in Huntington Beach for a few years, I always would go to Laguna Beach to ride with the Laguna RADs (Laguna-based underground mountain-biking club). I was a trials rider for 10 years before I picked up mountain biking from those trips to Laguna.

CN: Even though you won at world championships and national championships level in three countries in trials, mountain biking took over for you at some point. Tell me about the transition.

HR: In Europe, trials was a motorcycle and 20” bicycle sport. Then the word came along that there was this new sport of mountain biking evolving in the US and that one of the disciplines was trials. We heard that there were actually US trials riders who were sponsored! Even though trials riding was much more advanced in Europe, we were all amateurs; no-one was sponsored. In the US trials was just a small part of mountain biking. Kevin Norton, the US national trials champion, invited me over. He said ‘you have to come help with trials here, it's about to take off.' When I came over here, I got instant recognition.

CN: But trials in the US were done on mountain bikes, not 20” bikes...

HR: My skills were able to carry over. Back then they had these mountain bike stage races. You had to do everything; uphill, downhill, cross country and trials. All these mountain-bike stars - Tomac, Ned Overend - had to do the trials. At Mammoth, for example, there would be like 1,000 riders doing the trials competition. It was easy for me to do well. When the races broke up into specialised events, a small group of guys stuck with trials, but it was the hardest sport so most people opted out and it faded.

CN: You also split away from trials competitions?

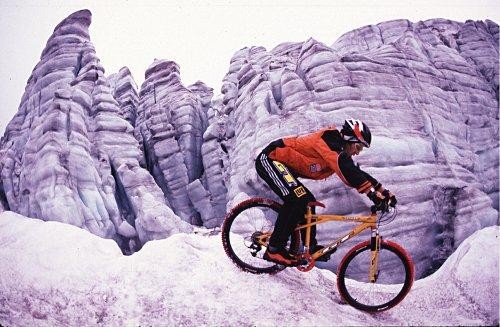

HR: For many years, I still competed in trials. I won the national championships and rode the world championships. Then, in the early '90's, I started doing videos. Many people tell me that was the beginning of freeriding; me taking my bike into these non-competitive environments like through waterfalls in Jamaica or down the slopes at Mammoth on the snow. I did urban sessions in San Francisco and rode on the Inca trail to Machu Picu and people remember it to this day. People were realising that mountain biking was not about racing.

CN: You're well supported by your sponsors. Was it always easy to convince them that what you were planning would bring them exposure?

HR: It didn't come overnight - I had to prove myself - but yes, they get what I do big time. The results speak for themselves. After the trip I did last year with Thomas Frischknecht (Alta Rezia Freeride Tour), we had 26 magazine features. A feature is like four to ten pages. That's about as much coverage as the whole world championships probably got. Plus we got TV and DVD's out of it! The stuff is really successful. These things have longevity as well. I look at DVD's that are seven years old and they don't look dated.

CN: You announced the formation of a charity last year. How has it been going?

HR: It's called Wheels 4 Life (www.wheels4life.org). We give bikes to people in need of transportation in third-world countries. I've seen how a bike can make a difference in a person's life. For us it's a toy. For them, a bike can mean the difference between going to school or taking a job that's a few miles away or not. We give bikes to health care workers so they can see more patients. There are literally millions of people out there who need bikes.

CN: How do you raise money?

HR: Fundraisers and donations. We put out some publicity and got support from people in the industry. A local school had a bake sale. One of the biggest bike races in Germany is tying my charity to their event, as is a festival in Switzerland. We also receive donations through the website. We take that money and buy bikes from a disributor that sells them in the places that need them most. The biggest obligation I have is to make sure the bikes end up in the right hands and we're looking at opportunities in the Philippines, Ethiopia, Ghana, Senegal - even an orphanage in Mexico.

CN: Do you have a goal in the number of bikes you'd like to see bought?

HR: The bikes cost between $100 and $150. When I started I said I wanted to buy 50 bikes. Since then, I've gone through the process of setting up a formal charity and we have bigger goals (Rey hinted at a fundraising goal that could buy 350 bikes this year alone). Once I'm big enough, I can buy a full container ship of bikes directly from China.

See also: Super, Super, Super and Spectacular! - Hans Rey and Thomas Frischknecht on the Alta Rezia Freeride Tour ( July 6, 2005)