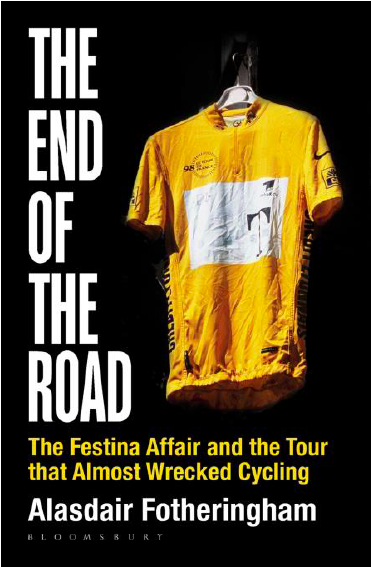

The End of the Road: The Festina Affair and the Tour that Almost Wrecked Cycling by Alasdair Fotheringham - Book Extract

Marco Pantani and the first mountain stage of the 1998 Tour de France

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following is an extract from The End of the Road: The Festina Affair and the Tour that Almost Wrecked Cycling by Alasdair Fotheringham, Bloomsbury Publishing, £18.99 Hardback /£10.99 eBook. It's the first day in the mountains from Pau to Luchon with German Jan Ullrich wearing the yellow jersey....

For the first six days, Pantani's advantage remained at 43 seconds on Ullrich, his position in the overall classification a long way down. In the time trial at Corrèze, he finished 4'21" seconds slower than Ullrich. Overall, as Matt Rendell points out in The Death of Marco Pantani, six more potential Tour winners – Abraham Olano, Laurent Jalabert, Evgeni Berzin, Luc Leblanc and outsider Bobby Julich all lay between Pantani and Ullrich. At that point, it looked like nothing but stage wins were possible for the Italian at most. Dire warnings were uttered by Luc Leblanc that Pantani was behind by a far smaller margin than in the 1997 Tour when the race had reached the mountains. But when Pantani finally made it on to the Tour's radar for the first time in the race, on the Col de Peyresourde climb in the Pyrenees, it looked to be no more than a symbolic reminder of the true identity of cycling's King of the Mountains. In terms of actual racing, Ullrich's strong ride on the first stage in the Pyrenees looked to be much more significant.

'Marco had not said anything about winning or attacking the night before,' Traversoni recalls. 'But he never would do.' Rather than table-thumping or gung-ho speeches, all Pantani would say prior to any mountain stage, in fact, was "tomorrow, I'm going to do my best". That morning [of the first stage in the Pyrenees], in fact, he was complaining about his breathing being rough. He wasn't that motivated and it was maybe too soon for him to tackle the first real mountain stage.'

While riders abandoned in droves – 17 went home that day, fuelling yet more speculation that illicit recovery products were notably absent by that point in the Tour – for the first two-thirds of the hardest stage of the race so far Telekom managed to keep their leader protected. Over the Aubisque and again over the Tourmalet, there was no question as to who was in charge: the pink-clad Telekom troops, with only Laurent Jalabert brave enough to test the waters close to the summit and then on the downhill section off the Col d'Aspin. The Frenchman's move caused some tension, but only up to a point: on the Peyresourde, as Ullrich himself came to the fore, Jalabert was reeled in. Then another top favourite, former World Champion Abraham Olano, who had crashed, also slid behind.

With several of the main challengers in difficulties, including 1994 Giro d'Italia winner and 1996 Tour leader Evgeni Berzin, Ullrich piled on the pressure. His margin of 59 seconds on Olano and 1'14" on Jalabert by the time the race had dropped down into Luchon, the stage finish, was not a knockout blow. But there was no doubt the German had the upper hand. Most of the nine riders alongside Ullrich were mountain climbers, with Bobby Julich the only talented time triallist to survive the cull, which saw the German back in yellow following its two-day 'loan' to Desbiens. As for Pantani, he had finished ahead of Ullrich, but his attack, a move around two kilometres from the summit of the Peyresourde, seemed inconsequential in the extreme. Too late to claim the stage win from fellow Italian Rodolfo Massi, Pantani's second place was enough to pull back 23 seconds on the German. But that was hardly a massive gain on a rider back in yellow and with a lead of nearly five minutes.

In fact the Tour's first mountain stage was seen as a major triumph for Ullrich. 'He's made a real advance,' argued Miguel Indurain. 'Pantani will have to attack on every mountain from here to Paris if he wants to win,' the Guardian observed. 'I'm going to attack every time I can, all the way to the finish,' Pantani said – but much later, according to Rendell, he also admitted, 'if I had won that stage, I'd have gone home'.

In the Telekom camp, meanwhile, Aldag says, 'there was a sensation after the time trial that we didn't know how we'd do it exactly, but we were going to win the Tour de France'. The first mountain stage had gone perfectly, too, with Riis and Udo Bölts working well as Ullrich's key climbing domestiques. It all looked to be going in the right direction.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The End of the Road: The Festina Affair and the Tour that Almost Wrecked Cycling by Alasdair Fotheringham is published by Bloomsbury and available now.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.